Anima, Animism, Animate: Ethnography after Authenticity

"She can’t quite let herself believe. But the data keep confirming. And on that evening when Patricia finally accepts what the measurements say, her limbs heat up and tears run down her face. For all she knows, she’s the first creature in the expanding adventure of life who has ever glimpsed this small but certain thing that evolution is up to. Life is talking to itself, and she has listened in." Richard Powers, The Overstory

"In time, it was Protestants and their descendants who identified themselves as the party of the present and the future, in contrast to the darkness and ignorance of the Catholic past. This judgment became policy in the northern European and British Protestant empires that replaced the southern European Catholic ones, as the “othering” of Catholic practice and belief got translated into an “othering” of all religious others who practiced the presence of the gods in some form. Making this distinction between “religion” and “superstition” (= special beings really present) was often the first step toward imperial domination." Robert Orsi, History and Presence

This is an essay about soul and power. It is about the real presence of soul as a constitutive part of the symbiotic real and what that means for the politics of truth.

The “symbiotic real” is a term I take from Timothy Morton (2017). It is Morton’s term for something like the biosphere, but the biosphere understood as embedded in a complex of lively materiality that extends well beyond the borders of what standard biological accounts of the biosphere might typically include: an ecology of living things nested in lively things.

Morton’s material complex is characterized by both porosity (the openness of objects, one to another) and interplay (the tangled dance of objects characterized by both attraction and withdrawal). Morton calls this porosity and interplay “realist magic” (2013). Realist magic is a play on the literary genre of magical realism. Magical realism is a narrative style that sets itself against the imperial projects of modernity by incorporating into the spaces and places of everyday life things and beings that are (for the modern) uncanny, mysterious, and unspeakable. It constitutes, in other words, a rejection of the imperialist notion that mechanical causality and scientific positivity have a monopoly on explaining the realness of things.

Realist magic, in a complementary anti-imperial fashion, amplifies the power of magical realism by affirming that “the realness of things” is indeed “bound up with a certain mystery, in these multiple senses: unspeakability, enclosure, withdrawal, secrecy” (2013, 19). In this, Morton plays a kind of judo with imperial modernity. He plays a kind of judo in that, rather than opposing magic to modern regimes of rationality, he instead plunders the authority of science by taking his readers on a tour through an endless variety of wonders that science itself—perhaps unwittingly—has offered to the contemporary world: quantum entanglement, the spritely play of the microbiome, the insatiable quest of all living things to get tangled up in each other, the organismal planet.

Realist magic is found not in the rejection of a fundamentally materialist science. It is found in the inability of materialist science to sustain an older, mechanistic view of reality. In this, imperial modernity finds itself confronted—on its own terms—with the essential mystery of the real. The symbiotic real is shot through with realist magic; thank you, science.

It is not, however, shot through with the real presence of soul, at least not “soul” as I intend to talk about it here. This, I argue, is both strange and a problem. It is strange because terms like “mystery” and “withdrawal” (and “negation” and “lack”) are formulations that have classically been associated with soul-talk. More importantly, it is a problem—and one that goes well beyond Morton’s evocative offerings. It is a problem because the lack of soul goes to the heart of the troubling politics of truth that continue to govern so much of contemporary thinking among North Atlantic elites.

The problem is signaled in the epigraph from Robert Orsi above. As Orsi (2018) explains, Europe (and its cultural, i.e., white, descendants) has been traumatically wounded by a bitter internecine fight among Protestant and Roman Catholic Christians. This is a fight in which secular Europe (despite its theological disavowals) has resolutely taken sides. The fight is about “the lived reality of special religious beings (among them saints, gods, embodied spirits, the dead, angels, and demons)” and the question of “their efficacious presence” (Orsi and Yerxa 2016, 120).

Secular Europe has taken sides inasmuch as the rejection of the idea of real presence has become the template for establishing the terms of proper rationality and civilization. The question of whether, and to what extent, a particular people conforms to the secular view of presence has become, to quote Orsi, “a lens for identifying, classifying, and ranking” them (Orsi and Yerxa 2016, 120). Such classification begins with a distinction between “religion” and “superstition” (i.e., special beings really present) and ends with a distinction between reality and illusion. A process that “was often the first step toward imperial domination” (121).

The sciences, and the human sciences in particular, have been essential. As European imperialism took hold, European elites needed experts to authenticate the difference between reason and savagery. Such authentication found one of its most lurid forms in the construction of “Museums of Man”—pantheons to European superiority. It was the task of the human scientist—the ethnographer, the archeologist, the orientalist—to arrange the material booty of colonial adventure (amulets, masks, bones, and bodies) and interpret them as the warrant for imperial subjugation (Handler 1986; Said 1979).

At the heart of this paternalism lies a contradiction. On the one side is a rejection of dualism. Reality is properly material. The wives of respectable colonial governors might still believe in something like the human soul. But the idea that unseen beings have something important to do with this-worldly affairs was flatly, and above all scientifically, dismissed as primitive silliness. And yet, at the same time, another duality, a political duality, remained in force. The European could see what the “savage” could not, because the European was free from superstition.

Which brings me to the trouble with Morton’s symbiotic real. I worry that a commitment to what William Connolly (2013; cf. Kohn 2013) usefully calls “protean monism”—a metaphysical commitment that underlies so many of the most interesting conceptual and political interventions elaborated in the human sciences today—inadvertently perpetuates the paternalistic denial of presence by other means.

It does this by relying on many of the same “perceptual sensitivities” (to use another of Connolly’s apt formulations) that underwrite and inform what we might call “old materialism.” 1 Old materialism, despite occasional flirtations with anticolonial politics, shares with the rest of the European old guard a distaste for what the colonial-era anthropologist EB Tylor categorized as animism: superstitious belief in things with anima—soul—whether totems, dream walkers, or the Eucharist. I worry that a newer materialism inadvertently shares this same distaste.

Hence Morton. It seems me that Morton fails to make room for real presence. To be clear: I do not think Morton’s realist magic needs to incorporate real presence in any explicit fashion. It just needs to resist the paternalistic temptation to rule it out of bounds in the first place. The reason I care is this: I do not think one can be anti-imperial and dismissive of real presence.

Getting there takes more than good intentions or even a willingness to embrace a more inclusive set of concepts, stories, or styles of reasoning. It requires, in addition, undertaking a sustained work on oneself (Mittermaier 2011; Foucault 2005; Smith 2013). There are candidate models for what such work might look like. I mention a few in the last section below. But what that work ultimately requires can only be discovered within the intimate contours of the places where each of us finds ourselves and the differences each of us seeks to make for ourselves and others.

Such work will inevitably cost something for those who take it up. Minimally, it will cost time and the ability to continue comfortably participating in the unacknowledged residues of colonial paternalism, residues that persist in the ways we act and talk, the ways our perceptual sensitivities continue to be disciplined by our disciplines, and in the haunting question of whose accounts of the real get to count as real.

More maximally, it will cost legibility in certain respectable intellectual settings. Do the subjectivational work of remaining open to real presence, and you may not be taken seriously. For those properly disciplined by the academy, sincere soul-talk remains somewhere between taboo and nonsense.

Such costs are a small price to pay. Small because they contribute to the dignified labor—the soulful work—of opening up a potential difference in one’s manner of sensing, thinking, and being, a difference that might be not only more authentic but more real.

The material that follows has been arranged in a modified ethnographic form. Most sections begin with material drawn from fieldwork I have conducted over several years in multiple biotech labs as well as with experimental collectives working at the interface of science, art, spirituality, and pedagogy.

I have, unavoidably, stylized these materials. In doing so, I have been conscious of the long history of deep thinking about the politics of such stylization and the privileges that get reproduced through them. In the case of the materials presented here, these usual hazards are intensified by the fact that I am using a reflection on biotech to think through my own struggles as an ethnographer working within a particular history of the politics of truth, a history haunted by colonial traumas—not least the paternalistic disregard for real presence.

I take solace in my stumbling efforts from wisdom offered by Stefania Pandolfo. Pandolfo (1997) reminds us that the real itself is interpersonal. That means any effort to do work with, for, and on oneself ultimately cannot be disentangled from the work we do with, for, and on those with whom we are traveling—human and more-than-human alike.

Pandolfo’s encouragement signals what are, I suspect, the real stakes of the stories I tell. The work we do inevitably does us. And not only—as the old saying has it—do “you only get out what you put in,” you always get out what you put in. The terms of that dangerous exchange lie at the heart of this essay.

Soulwork: The Persistence of the Animate

M. knits his brow. “It will not work.” He emphasizes each word. He is either angry or frustrated. It is difficult to tell. It is difficult because the rest of us in the lab group have never seen him like this. The closet-like conference room feels too small and warm. There is no place to escape his disapproval. Most of us look at our notes. The hum of the subzero freezers outside the room makes our silence conspicuous.

He is the lead scientist on the project. He has the right to be upset. It is the third time he has had to step in to redo the complete set of experiments. Weeks have become months, and months a full year. But his look of defeat is the real reason for our collective shame. It somehow seems worse worn on his handsome, square face.

He once confided to me that his father was disappointed in him for becoming a scientist, despite the long journey from rural India to the San Francisco metropole. “The men in my family, the oldest sons, always become religious teachers.” In my naïvely American way, I was surprised, forgetting for a moment that the scientist has been a figure of secular colonialism for nearly two hundred years.

The first time he has to redo the experiments, he bears it patiently, knowing how difficult and subtle even such a basic experiment can be. The second time, his frustration begins to show. He takes his frustrations out on what he sees to be the intrusion of Silicon Valley branding into the lab. “Why do they insist on saying we are building an ‘Expression Operating Unit’? Why not ‘gene cassette’ or ‘open reading frame,’ like everybody else?”

So, we try a third time. This round, the “Expression Operating Unit” is utterly simple, built of only three designed components. The components are varied incrementally in each iteration, a stepwise approach designed to tune data in such a way that each construct can be certified reliable.

M. knows it is all embarrassingly mundane. He comes from a celebrated molecular biophysics lab in San Francisco. Despite its billing, our work really has nothing of the grand aspirations to “rewrite life” that have come to dominate the rhetorics of digital biology.

The upside of such a digital imagination is that it seems primed to capitalize on the Valley’s ability to turn data into power and power into wealth. The downside, as M. knows all too well, is that living things resist these analogies. Algorithms execute in a stepwise fashion. Living things do what they want until you get in their way.

In Georges Canguilhem’s tidy phrase, “Life, whatever form it may take, involves self-preservation by means of self-regulation” (2000, 205). Life is, in this sense, “capable of error” (2008, 134). You engineer living things to behave in a certain way, and as often as not they simply compensate for your “mistakes” and go on self-regulating. Living things have anima, to use the Latin: vitality, will, soul.

Today M. has finally had enough. “The cells don’t want to do it.” He looks briefly embarrassed by his own personification, but he does not correct himself. He does not correct himself because he knows he is right. The trouble with this whole enterprise is that it cannot face up to what he has just confessed.

Contemporary biotech begins with a seduction and ends with a disavowal. The seduction is the liveliness of the living—its self-regulation, elegantly choreographed with an environment, a relation always porous and partial and unsettled. This choreography allows it to commune among other living and nonliving things, to sense, interpret, adapt, accept, and push back.

The disavowal begins with an algorithmic imagination born out of the Valley’s old dreams, high math, and a studied success with turning messy, unstructured data into discrete and automated variables—ones and zeros that render data executable, that is to say, governable in a more or less automated and consistent fashion.

This motion of seduction and refusal operates in a zone of life’s normativity. That normativity does not begin with a judgement on the part of the biotechnological designer. It begins, rather, in the interplay between the living being and its milieu.

That interplay is always situated. Better, it is always embedded (Taylor 2007). It is, to crib Giuseppe Longo (2018), always this living being here, with this body, in this place, at this moment. This means that even a biologist must remain resolutely historicist to properly grasp the ontology of the living.

The living being resists any settled definition because it establishes its own norm of being in relation to an ever-shifting milieu. Hence its normativity. Living things preserve, regulate, and adapt. All these actions are evaluative and linked to processes of self-normalization. Such self-normalization is always partial and circumscribed relative to the milieu.

A historicist definition of the living might look something like this: life is that feature of the symbiotic real that establishes its own normativity—self-preservation through self-regulation. Moreover, life is that feature of the symbiotic real capable of establishing new norms for itself as circumstances change.

Hence Canguilhem’s guiding rule of thumb: life is capable of error. Treating living things as living means approaching them as capable of error.

The trouble with our lab group’s project was not its relative complexity. The trouble is that we tried to harness the functional potency implied in the living while minimizing the normativity of the living out of which that potency arises. This strategy was commonplace.

Our approach was to treat the organism’s genome as a repository of motifs, which may have, at one time, been keyed to a lively relationship between a living being and its milieu but now is read as an inert code, whose only relevant context is interactions that impact the operations of programmed DNA.

Yet as any biologist worth their salt knows, and as has been discussed too many times to warrant revisiting here, such code is never enough. Even the genome, so seemingly stable, determines almost nothing on its own. The dynamics of self-regulation and renormalization, to borrow from Morton, are always “non-total,” “jagged,” “incomplete” (2017, 19).

This means that the living being and its milieu—including other beings—have to constitute and experiment and negotiate the terms of their mutual normativity. Self-regulation gets worked out in what Morton (2017) describes as a politico-ontological space of solidarity. Life in its spatial dimensions, that is, in a distributed space of relations, seeks camaraderie by way of adjusted errors. Life is an imperfect democracy.

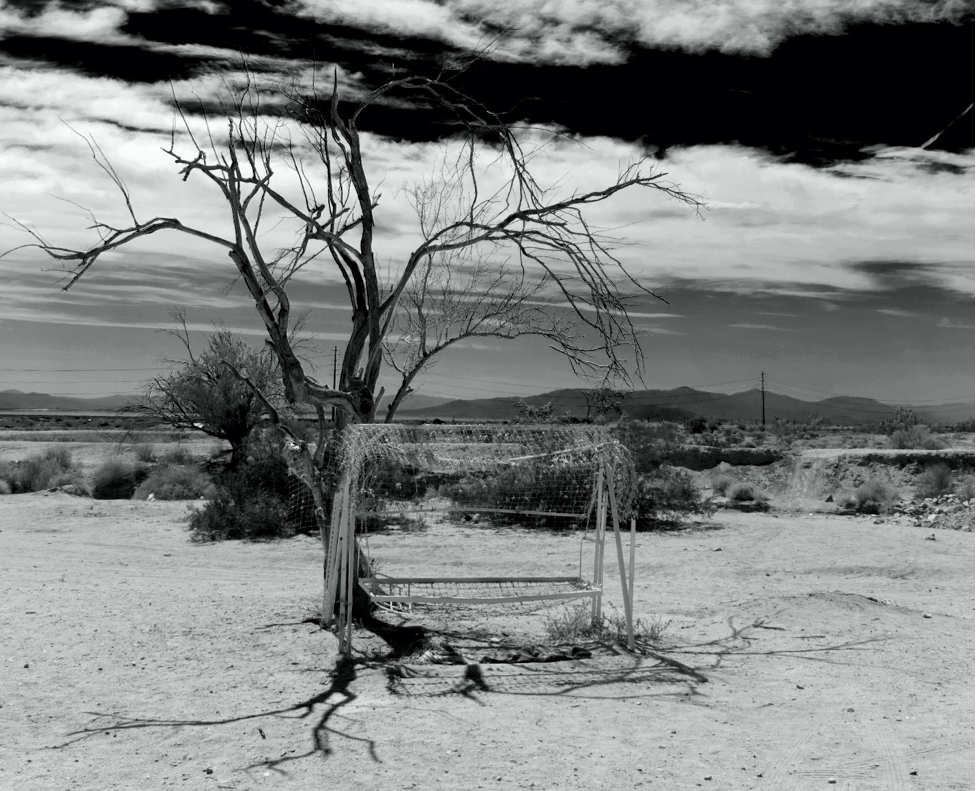

At the same time, the living being in relation to its milieu is also and simultaneously worked out in what could be called a spiritual-ontological place of embeddedness—spiritual in the sense that its work of renormalization is indexed to the labor of becoming what it needs to be in order to belong. Life has a depth dimension written by evolution into, and as, its body. It bears a history of where it comes from, where it calls home. Life is about solidarity, but it is also about belonging. Life is place based.

Hence the trouble in the lab. The lab must enact a twofold disruption of the living. It must interfere in its straining-for-solidarity and it must remove all traces of place. It must sever solidarity and disembed the living from its home.

If the Latin term for soul, anima, means, at once, “to have life, will, and desire,” the term “animate” (pronounced with an -et at the end, like “bet”) denotes a being “being vivified or quickened.” Animate (same pronunciation) was linked to the verb “to animate,” “to make live, to breathe life into, to quicken, to vivify.” 2

The notion of the animate points to the idea, framed by Orsi above, of an unseen presence. A real presence. Unseen in the sense that there is something there, but just out of reach—an unspeakable withdrawal, in the sense of Morton’s realist magic. It is the presence of a thing that has a center of being and self-regulates, if always in an incomplete relation to others.

This is what biotechnologists must contend with in order to get their experiments to work. Of course, they would never frame it this way. Like EB Tylor, they would likely dismiss such a presence as trucking in animism. Yet this is why they have to spend so much time severing and disembedding, as I detail below.

One can contrast the animate with the animated (this time pronounced -ay, like “made”). In everyday English, “animated” means “to appear alive by being made to move, such as an animated film or a video game.” This is a good way of describing what is going on in biotech. They do not want a lively thing on their hands. They want something that does what it is “told” to do. They do not want, that is to say, a living/soulful being. They want an automated being. Biotech wants automation, not animation. 3

M. has come to find the whole enterprise disenchanting. “It’s not fun anymore,” he later tells me. I see the defeat in his body. It has only been a year. But then again, it has been a year. This whole thing was supposed to be the warm-up act for something more serious. M.—to put it in terms he would not use but would not refuse—is done being disciplined by disenchantment.

The term “disenchantment,” understood in a technical sense, is usually associated with the writings of Max Weber (2004) on the question and problem of modernity. The term in German is Entzauberung, literally demagification, the breaking of the spell of superstition that unleashes the rationalization of life.

To be disciplined by disenchantment, as Weber bitingly insists, is to accept the eradication of religion and spirituality (“magical beings”) from modern modes of living. It is to make a decisive cut between what is real and what is wishful thinking.

Disenchantment disaggregates the symbiotic real. Or, as Ernst Cassirer (1953) perceptively observed, well before Foucault (2003) took his deep and singular dive into the subject: to be modern is to be individuated. And to be individuated is to be situated in a world of other individuated things. In this sense, disenchantment can be opposed not so much to “magic” but to entanglement.

The only consolation, as I discuss below, is a fleeting illusion of independence and thereby the hope of achieving a truer authenticity. This longing for authenticity is a response to a history wounded by an ontology of individuation. One could say that the all-too-modern imperative to be a more authentic individual is one potential response to the disciplinary regimes that render us individuated, which is to say animated. The trouble is, it doesn’t work.

The Animated: Severing and Disembedding

S.A. tries to burst into the room. The heavy boardroom door pneumatically resists his enthusiasm.

We are used to his charged energy, a contrast to M.’s quiet steadiness. But today is different. We can feel that excitement, that extra bit of a lift in the lilting gait he gets when there is something worth talking about.

“There is an embargo, so you can’t tell anybody about this.” A reporter just texted him to get a response. The news will hit the international press the next morning. The timing will prove timely—no wars or political scandals to chase scientific news off the front pages.

The splash will be, in part, Craig Venter himself. In the years since his high-profile arms race with the US government in the human genome project, he has become even more mediagenic. He cultivates his outsized reputation for rule breaking, for leveraging the power of information technology, and, above all, for good press.

“The Venter Institute will say it is a scientific achievement,” S.A. begins. “But not quite. It’s an engineering achievement. They’ve invented a new technology—a method really. It’s a big deal, but most people will miss that part.”

He pauses. No one says anything. He settles into one of the Herman Miller wingbacks and holds up his hand, fingers spread. “Imagine these are branches on a bacterial family tree.” He wiggles his fingers. “Imagine each of these is a strain of bacteria. Closely related, but each different in important ways.”

He touches his pointer finger with his other hand. “They started out with this strain. From a goat, I think. It doesn’t really matter.” Now he squeezes the tip of the finger, his voice leaning into it. “They sequenced its genome and put it on a computer. No problem. But they wanted a minimal genome. It took years to work out which elements they could strip away.”

He looks up. “But now they’ve assembled it all in one go. Think about it. Thousands of oglios successfully joined in vivo. Printed chemically, assembled in yeast with none of the usual scarring and errors. The whole genome.”

None of us, apart from M., have been doing this long enough to fully appreciate what he is telling us. He tries again. “The synthesized genome was originally taken from this one.” Pointer finger again. “It was placed in this one.” He moves his little finger. “After a handful of population doublings, like six or so, that synthesized genome replaced all the molecules in the second bacterium.” He leans back. “Phylogenetic discontinuity.”

When Morton first explains the symbiotic real, he offers this example: the strange and beautiful biological exchange between a mother and her baby. When the baby is born, a host of nonhuman beings that constellate to help constitute the mother’s body—the trillions of cells in her microbiome—is given to the child. It is an inheritance bequeathed from one body to another. The baby, for her part, induces cascades of chemical changes within her mother: touch strengthens the immune system; eye gazing animates the nervous system. At its best, it is a tangle of loved and beloved.

This exchange underscores the violence of what Morton (2017) calls the Severing. The Severing is Morton’s name for the myriad ways modernity gets constituted by the presumption of an ontological cut between one thing and another—between mind and matter, say, or space and time, reason and superstition, the modern and the primitive. The Severing is epitomized, above all, by the modern presumption of a fundamental difference between what Jacques Lacan designated as reality (the way human people orient themselves in their worlds) and the Real (the ecological tangle of human and nonhuman relations through which such orientation is carried out).

This presumption once guaranteed the job of the colonial human scientist—the ethnographer could see what the native could not: the difference between social construction (the native’s world) and the really real (the scientist’s world). Today, it underwrites the operations of biotechnology, but at a potentially terrible cost: “Since nonhumans compose our very bodies,” Morton writes, “it’s likely that the Severing has produced physical as well as psychic effects, scars of the rip between reality and the real. One thinks of the Platonic dichotomy of body and soul: the chariot and the charioteer, the chariot whose horses are always trying to pull away in another direction” (2017, 44).

The Severing is a wound. That wound is traumatic. It is traumatic in that it gets obsessively reenacted. It gets obsessively reenacted because the structural conditions of the Severing (i.e., the conditions that make it make sense) are themselves sustained by what, following Charles Taylor (2007), we might call the Great Disembedding. Taylor coined this term to describe the historical processes by way of which secular Europe came to constitute itself as separate from its own history (i.e., “progress”).

The Great Disembedding began, on Taylor’s account, with the shifts internal to European Christianity that slowly but steadily began to displace the religion of collective ritual with the policed strictures of a more personal piety. Taylor traces out the multitude of little, everyday interventions that together had the effect of uprooting the individual from the human social, the human social from the ecological, and the ecological and the cosmological.

Like the Severing, Taylor’s story of spiritual politics is both violent and traumatic. It is violent in as far as it does away with a manner of being in the world that Taylor calls “porous” (the experience of being open to and defined by the presence of the real). It replaces that way of being with a “buffered” sense of the self (closed and individuated). This buffered sense of self gets narrated by those who help bring it into being as a mere subtraction story in which superstition is stripped away and nothing of real value is lost. Taylor, alongside other theorists of modernity from Durkheim to Foucault, understands that the buffered self is actually produced through the operations of power, operations that have to be continually reenacted.

Taken together, the Severing and the Great Disembedding form a matrix structured along two axes. The first axis, corresponding to the Severing, can be said to operate across the “breadth” of relational space. The Severing names the disruption of living beings in the ecological solidarity of their relation to a milieu. In this way, the Severing measures out the cost of modernity’s ontological traumas in terms of lost solidarity.

Disembedding, the second axis, can be said to operate in the “depth” dimension of relational space. Disembedding names the disruption of the historical relation of living beings to place. In this way, the Great Disembedding measures out the cost of modernity’s ontological traumas in terms of belonging.

This matrix of disruption has opened a difference—an institutional and existential distance—between what I designate as the animate and the animated. That difference is constituted like a gradation, a spectrum, in the heart of which one finds a sort of ontological purgatory: a space where living things, like those in biotech labs, get suspended between the one and the other.

Twelve hours after our encounter with S.A., the scientific paper will be published. The paper itself (Gibson et al. 2010) will be modest and staid, as the genre demands. The narrative attached to the paper by the Venter Institute’s media team will be breathless and triumphant: “Life is software that creates its own hardware.” Some in the press will be sanguine: “Researchers say they created a synthetic cell.” Others will profit from the sensation that Venter himself is seeking: “Immaculate creation: birth of the first synthetic cell.”

It is, for some, a bit chilling, this image of programmable life. But the metaphor has been around for so long the reified digital analogies slide by mostly unnoticed. The intuition that something older and more fundamental is at stake is not lost on everyone. Organizations and individuals long entrenched in the fight over globalism, agribusiness, and environmental colonialism see that this is a next step in the long and violent history of trying to tidy up living things and make them cooperate with the will of a North Atlantic governor. To them, the imperial resonances are clear.

Predictably, these anti-imperial criticisms get slotted as antiscience, antimarket, or maybe just Romantic. That these criticisms are rooted in hard-won intuitions about the tangled composition of living things and that the traumatic harm done to humans and nonhumans alike when severing and disembedding get actualized as projects of management, ordering, separation, and extraction strike most as far away and less impressive than biotech’s algorithmic potential.

Presence: Normativity and the Normed

G.C. leans forward onto his elbows and repositions the short tabletop mic. The amplified rustle of his movements abruptly quiets the room, like lights dimming before a performance. The sudden hush leaves an energy of anticipation, focusing the collective attention of the overcrowded hearing room.

G.C. is relaxed. It is not so much that he is in his element. It is that none of this bothers him. His affable reassurance strikes a contrast to Venter, just to his left. Venter also seems to be in his element, but more like a showman. His combative style and impatience with the committee’s questions communicate the high-handed annoyance of someone reprimanding “the help.”

G.C. is Venter’s competitor. Though on this day, he is not yet a star. It is still Venter’s show. Within three years that will change. Venter, biotech’s “bad boy,” will be out, quietly removed from his company’s website—his talk of “curing aging” sounding too much like a transhumanist invitation to Elysium.

G.C. will move in the opposite direction. His work in gene editing—extending the powerful CRISPR CAS-9 from bacterial cells to cells with a nucleus, most importantly human embryos—will be only the most visible factor in his rise to scientific celebrity. He will be equally transhumanist, only accessible and charismatic.

“We’ve gone well beyond manual genome engineering. We have gone beyond minimal cells to these fast, robust, useful cells.” Venter has just finished extolling the virtues of his minimal cell; but the audience has moved on to G.C.’s story. “The question is, why we do things on a genome scale? There’s a safety and security reasons [sic] for doing things on the genome scale.” 4

Scale, safety, security. The DC audience relaxes: evolutionary self-regulation sounds a lot like political regulation. A mood of mutual recognition takes hold. G.C.’s own successes, and what they signal, slip by unnoticed. His lab has incorporated hundreds of directed changes into cells. They are finding new ways to harness the speed and power of computers. And a few years out, gene editing will supercharge their own efforts to create bodies without biological inheritance.

A few weeks earlier, in the days immediately following Venter’s announcement, G.C. was one of the first to insist that, however important, this was a technical and not a scientific breakthrough: “Printing out a copy of an ancient text isn’t the same as understanding the language” (Nature 2010, 422). The comment is suited to the cultural common sense and is meant to provide reassurance. Though why, in an age of “big tech” and its impacts, a technical breakthrough is less game changing than a biological breakthrough, no one asks nor answers.

Maybe it is a throwaway line, a bluff against a competitor. Or maybe it is intended to soothe disquieted religious sensibilities. But G.C. adds: “[H]as the JCVI created ‘new life’ and tested vitalism? Not really” (422).

The word surprises me, and I wonder if it catches anyone else’s attention. Vitalism: even the theologians interviewed will shrug. It is as if G.C. wants to say, “Don’t worry, this has nothing to do with bodies and souls.”

Yet that is not obvious at all. G.C. is onto something, despite himself. The whole enterprise, after all, turns on showing that a computer-mediated bundle of curated information can be transmuted into a manageable living thing.

Juxtaposed to G.C., one column over, is A.C. A.C. disagrees: “This is a game changer.” It has everything to do with vitalism, he insists:

"[Vitalists] claimed that life could never be explained simply mechanistically. Nor could it be artificially created by synthesizing molecules. [It required] a vital force that was the ineffable current distinguishing the living from the inorganic. No manipulations of the inorganic would permit the creation of any living thing." (423)

He names names: Galen, Bergson, Pasteur, Driesch. He adds Christianity, Islam, Judaism. “All of these deeply entrenched metaphysical views,” he tells the reader, “are cast into doubt by the demonstration that life can be created from non-living parts” (423).

Whether Christianity, Islam, and Judaism can reasonably be cast as “metaphysical views” will not matter to most of his readers. They understand what he is signaling. What catches attention is the kicker: “[Venter’s] work would seem to extinguish the argument that life requires a special force or power to exist. [. . .] In my view, this makes it one of the most important scientific achievements in the history of mankind” (423).

The trouble with the vitalists, for A.C., is not that they think living things are actually alive. A.C. does too. The trouble is that they think living things are different, special somehow, more than mechanical concatenations of nonliving parts.

But it is the nonliving that is the source of the trouble for the vitalists, not the living. It is a subtlety that A.C. overlooks in his rush to praise Venter. Vitalism makes sense to Bergson and others not because they believe in some immaterial ghost haunting mere matter but because vitalism makes manifest their stand against the dominant scientific view—so unconsciously articulated by A.C.—according to which everything is taken to be nonliving, including the living (Bergson 2001; Deleuze 1988). They know that such a view is as political as it is metaphysical (Jonas 2001; Merleau-Ponty 2013).

All of this would seem to underscore the radically anti-imperial credentials of a project like Morton’s. His refusal of a nonliving view of the real is simultaneously a refusal of the whole industry of authority built on that view. It would seem. I signal hesitation because, despite the crucial differences between A.C.’s quick-and-dirty dismissal of vitalism and the complexity of Morton’s new materialism, there is a discomfiting resonance between the two.

That resonance concerns the question of whose account of the real really gets to count. A.C. easily dismisses Christianity, Judaism, and Islam as just so many “deeply entrenched metaphysical views” (read: “superstitious believers in invisible beings”). His dismissal drips with a derision that readers of Morton will, unfortunately, recognize.

Whenever Morton needs a boogeyman, someone to blame for the Severing, he points an accusatory finger at Religion. To take a typically biting example, Morton says about the Severing: “You are either in church or you are thumbing your nose at church. In either case, there is a church” (2017, 60). Morton does not need to explain what he means. He just gives his readers a knowing wink.

The wink is not surprising. After all, the unmasking of false consciousness and the dangerous correlation of false consciousness with religious practice stands at the headwaters of old materialism. Like the old materialists, Morton is resolute about the need to abandon religion to achieve anything like a politics adequate to the ontological demands of the day.

That this posture is understandable goes without saying. The institutional church in Europe in the nineteenth century struggled mightily to retain its former privileges and did so, in part, by deepening its connections to capital. That struggle and those connections produced paroxysms of power keyed to a desire for near-absolute clerical authority.

There is a twist, however. Old materialism’s rejection of clerical authority was hypermodern, not anti-imperialist. It may have been monist in its metaphysics, but it accepted as the cultural common sense that the lived experience of real presence could only be a sign and signal of superstition. While colonialists were judging animism as irrational abroad, that same paternalism was turned against working-class folk on the continent.

The imperial insistence that the material is the only real world impacted the lives of these working stiffs as a judgement against their fitness to determine the terms of their own self-regulation. And the loss of their privilege to self-regulate ultimately redounded to a loss of the means to self-preserve, as it did for those in the colonies.

Whether Morton (or A.C., for that matter) likes religion is immaterial. What is material is that his regular and insistent use of antireligious cultural codes interferes with the anti-imperialist impulse of realist magic. It interferes with that impulse because these codes reactivate a colonial judgement against those deemed “irrational” and “superstitious,” thereby justifying, yet again, their potential subjugation.

To be sure, the Catholic missionaries and imperialists from Spain and Portugal were no less violent than those from England or the Netherlands. The point here is not to defend the Roman Church, which has too much blood on its own hands to escape Morton’s rhetorical savaging. The point, rather, is that—to pick just one example—even animists in the Americas who felt the full genocidal force of Catholic imperialism were able to find ways of resisting the church without throwing out the proverbial baby with the bathwater. Real presence remained, for them, real.

In light of these legacies, it is important to remember that the question of vitalism turns less on some theological notion of “vital force” and more on the proposition, held by vitalists of both monist and dualist varieties, that life has its own specificity and that this specificity is marked by presence.

The presence of the living adheres in its normativity. Recall Canguilhem: “Life, whatever form it may take, involves self-preservation by means of self-regulation” (2000, 205). The living thus persists as its own ontological rule of thumb—a vital maxim, if you will: if you see something that tends toward ontological solidarity and belonging, chances are, it’s alive.

For Morton, it is precisely the ubiquity of such solidarity and belonging that constitutes the warrant for his realist magic. The living is capacious. It is everywhere. (Symbionts all the way down.) Yet even cast capaciously, the living signals presence. It signals presence not because it is rare or special (though the latter is certainly true). It signals presence because the experience of the animate can be contrasted to that of the animated. The animated can be thought of as the animate fighting to save its presence.

The eradication of presence from the realm of intellectual respectability is the sign and signal of a North Atlantic culture of superiority. Modern science, and scientific materialism in particular, is the inheritor of this legacy. Genomics and synthetic genomics carry on the tradition. The temptation for other North Atlantic elites to do the same is itself ever present.

People in genomics do not carry on the tradition because they are any more consciously imperial than those who work just beyond their labs. They carry on the tradition because they operate on and with a machinery whose modalities rely entirely on a striving to reduce the normative living thing to the normed—to the status of a being whose functional purpose can be set in advance and regulated.

Practiced Disenchantment: The Afterlife of Presence

The first thing you do when you join a lab is undergo safety training. The stated rationale, as the online modules explain at length, is this: if you do something wrong, you might unwittingly destroy not only the biological constructs you are working on, but you could kill yourself and your friends as well. These trainings are designed to scare the hell out of you. It is the sure road to compliance.

There is a second unstated (and no doubt unconscious) rationale, as well. The trainings are a master class in modernist ontology. They are, thereby, also a lesson in an assiduously modern ethic (Rabinow and Bennett 2012). You learn the ontology to master the ethic; you learn the ethic to reproduce the ontology (Thurtle and Mitchell 2012).

The ontological training begins with a prime mandate: never let anything in the lab touch anything else. The “anything” is really the biological samples. There are living things swarming the surface of almost all built environments. Biological samples, you are told, are easily “contaminated.” Which means, like all living things, they want to get tangled up with other biological stuff. Hence the prime mandate.

The trouble, it turns out, is not really the safety—at least not a good deal of the time. The trouble is that the whole apparatus is propped up by the presumption that you have to separate everything from everything else, materially, conceptually, and biologically, in order to manage the unruliness of the living.

The methodological demands of such ontological management get translated into an operative epistemology: mastering techniques of severing and disembedding—wearing the proper gloves, using the proper containers, the proper freezers, and so on—is taken to be vital to understanding truths about the realness of things.

All of this is a strangely elaborate fiction. It is strangely elaborate in that it signals that the lab does not actually study the animate. It studies things that have been pulled apart, separated into vessels, tanks, and temperatures, and normed.

It is equally strange because virtually no one in biotech has any illusions about the fundamentally ecological character of the living. If you were to take the time to explain Morton’s symbiotic real over beers, say, most biologists would simply shrug in agreement: fancy language for a basic fact.

The contradiction is hidden in plain sight. Life makes manifest the magic of the symbiotic real. That means, if you want to work on it in a way that renders it animated rather than animate, you have to work quite hard to pull it off. To get the work of the lab to work, in other words, one has to conduct oneself as if the world is disenchanted.

In 1917, Weber delivered “Science as a Vocation.” Cast in the tradition of “religious callings,” Weber exhorted his audience of aspiring scientists to take up their work in a properly modern manner. To be properly modern, he told them, is to be guided, in everything one does, by the presumption that there are no mysterious forces left in the world: “modern man” no longer needs to “have recourse to magic” in order to reshape the world (2004, 13).

Such a calculative approach requires sacrifice, Weber insisted. Calculative reason may feel like it adds up—as if science will lead us to a more comprehensive view of reality and thereby a deeper connection to the real. But this progressive motion is only “progress” in the sense of constant change.

Science lived as a vocation thus requires an active ascetic restraint, one indexed to a specific metaphysics: the scientist cannot answer the question of how we should live our lives because they operate in a world that has been evacuated of any real presence and thereby any proper meaning. For those who cannot bear up under the strain, Weber concluded, the doors of the old churches remain wide open.

More than a century on, Weber’s vocation lectures stand as arguably the clearest and most systematic articulation of a modern ethic of disenchantment. Given the profile of the lectures, it is easy to forget that his meditations on disenchantment began almost two decades earlier, in his writings on capitalism and the Protestant ethic (2001). In those writings, Weber argued that long before the figure of the disenchanted scientist came along, it was the worldly calling of the Protestant that required ascetic restraint.

The ascetic Protestant was bound by the belief that the Church and its sacraments could no longer provide a sure road to salvation—there was no real divine presence left in the Eucharist. And if there was no real presence in the bread and wine, there was no real way for humans to participate in the making of their own salvation (Weber 2001; Orsi 2018).

Disenchantment thus brought with it the “terrible loneliness” of the individuated soul standing alone in judgement before an otherworldly God. For the Protestant, the loss of any direct participation in the means of salvation had the effect of disembedding both “Man” and God from a world otherwise shot through with presence. The individual soul, thus torn from the cosmos, was left to play out a role on the stage of divine judgement.

The cruel twist was that it did not really matter how good the performance was. Neither the assurance of collective ritual nor the merit of work on oneself could make the performance any more convincing to an audience of one. One could only be sincere and hope for the best.

Charles Taylor (2007) has detailed the unsettlingly banal terms of this evacuation of presence. For those at the heart of the church, these transformations may have been experienced as theological. For most everyone else—first in Europe and then beyond—it was experienced as an uprooting.

The uprooting of the individual from an enchanted world constituted a systematic political makeover, one composed of regulated, which is to say, normed, modifications of behavior. Pews were put in churches and seats in schools to pacify the body. Hospital rooms, prison cells, and industrial divisions of labor individuated the pacified body to maximize productivity. And the productive classes were made to wash, abstain from drink, and sleep in their own beds to turn virtue into profit.

Such regimes, enforced at once by changing social norms and reworked institutional arrangements, ensured that disenchantment could be scaled. Missionaries from Europe, sailing on colonial vessels, offered the “savage” much more than the word of God. To be properly Christian one had to be properly civilized, and to be properly civilized one had to be disenchanted (Orsi 2018).

For many Europeans, the loss of presence was the price to be paid for escaping out from under the power and perceived corruption of the Roman Church. Indeed, the spiritual politics of this liberation was warrant enough for recasting presence as superstition. Yet that warrant does not diminish the pathos one can see with the benefit of hindsight. The Protestant might have been seeking freedom from clerical authority, but it cost her a place of belonging in a tangled world.

That cost is one that has now accrued to all of those in Europe and beyond whose lively relation to the presence of the gods, or the souls of the dead, or angels, or karma, or witchcraft has been judged superstitious by those policing the difference between reality and the real.

And therein lie the roots of an eventual coincidence between a Protestant resignation and a properly modern scientific vocation: if the world has no mysterious forces left in it, then those forces cannot be manipulated to salvific effect—whether by science or by religion. To think otherwise is to suffer false consciousness, which is to say, enchantment. Colonial paternalism is only a small step away.

It is for this reason that Weber (2004) scolds “big children in editorial offices” for acting like Nietzsche’s “last men who invented happiness,” as though science could offer a return to an older magic. Despite such Nietzschean aspirations, Weber insists, scientists cannot get back on the other side of a lost cosmos.

Yet, it seems that this is precisely what biotech is being positioned to do. Biotechnologists today find themselves in a situation in which Weber’s scientific ethic has been utterly naturalized—scientists by and large, and biotechnologists in particular, take it for granted that the really real is disenchanted.

Biotechnologists, lab safety notwithstanding, have been institutionally freed from anything like a conscious commitment to the ascetic labor Weber extolled. In doing so, they have been put—they have put themselves—in a position where they cannot see the ways in which the work that they are doing is doing them. Proceeding on dreams of exploiting the animate by way of the animated, they tacitly reproduce the evacuation of presence. By reproducing the evacuation of presence, they enjoin themselves to the imperial refusal of solidarity and belonging.

Decolonial Equipment: Authenticity and the Real

B. drops her chin, thinking. She looks back up again. The hesitation is surprising. In our previous conversations, her words have always been delivered with unapologetic directness.

Even in hesitation, her manner is precise. Her old-world cultivation is matched to the angular lines of her patrician, almost disapproving, face. “I don’t think Powers has what everyone says he has,” she says. She smiles. It does not reach her eyes.

She is talking about Richard Powers. Powers has just received the Pulitzer Prize for his new book The Overstory, a book that draws together the threads of art, science, and spirituality, which B. also weaves. “I understand why,” she admits, shrugging. “But I don’t think the magic is as easy as he makes it out to be.”

The magic she is talking about is the presence of vital things, in the case of Powers’s book, trees: the way they talk to each other, care for each other, care for humans and nonhumans. “Plants eat light and air and water,” Powers writes, “and the stored energy goes on to make and do all things” (2018, 124).

“He is sentimental.” Now she laughs, surprised by her own sacrilege. Among her people—that set of writers and artists in the city who mix galas with vintage clothes and upstate farming—criticizing Powers is out of bounds.

“The sentimentality works,” she concedes. It makes it all seem real, accessible. It lets Powers turn magical realism into the kind of realist magic Morton argues for. Where magical realism brings elements of the fantastical and drops them down into everyday life, Powers refuses the economy of the exceptional altogether.

And that is the sticking point for B. It is not that she disagrees. B. takes realist magic utterly seriously. It is just that Powers, like other writers today, unwittingly cashes in on the now century-long dreams of disenchantment, the kind that underwrites biotech.

“If you just let go of superstition,” these dreams tell you, “and if you just refuse the idea that the world is filled with unseen forces for just a moment, science will do its work.” And lo and behold, in the end, everything turns out alright. Science confirms the magic. The epigraph from Powers at the start of this paper makes the point.

“It doesn’t cost us anything to agree with Powers,” B. says. “We already believe in science.” What gets B. is that science operates on the assumption that such as we are, without any real change in ourselves, without any real work on our souls, or relationships, or perceptual sensitivities, we have right of access to the truth. For B. it is the other way around (cf. Foucault 2005).

It occurs to me later, when I am working through my fieldnotes, that B. lives much of her life as an arbiter of authenticity, weighing the inauthentic against the real—just as she has with Powers. This is not a criticism. Other people seek her out for just this reason. She lives much of her life in spaces defined, simultaneously, by a palpable desire to encounter something genuinely real through art or science and by the desire to be witnessed participating in that genuineness and to get credit for it.

B. herself, meanwhile, is assiduously ascetic about the superficial lures that draw other people into these seemingly genuine spaces. She is the one who keeps it all on track, by keeping track of whether something is the genuine article or not.

I suspect B. is able to do this for others because she has dedicated herself to living in that difficult and precarious zone between being authentic and being real. The zone is difficult because pursuing the imperative to live authentically is a labor that requires vigilant self-monitoring combined with a taste for soul. It is precarious because the goal of this vigilant labor is to become real oneself, which requires being embedded in an unconscious way of life. That means one has to seek consciously and sincerely to embody norms of authenticity while also trying to just be oneself.

The longing to be more authentic has become a cultural imperative (Trilling 2009; Taylor 2018). That imperative arises out of the same ontological traumas that have opened up the purgatorial space between the animate and the animated—the matrix of severing and disembedding. And in a fashion parallel to the animate and the animated, one cannot get to real by being authentic, despite the impulse to try.

By being severed, one’s ontological solidarity falters, creating just enough space to observe oneself over against the inauthenticity of others. The Severing produces an individuation whose only available responses seem to be conformity or authenticity. By being disembedded, one’s place in the world, one’s ontological belonging, is no longer given. A role must be selected and tried out. Where the Protestant soul stood alone before God, secular moderns stand alone before the mirror of their own identity.

We play these roles for ourselves and then we play them for others. The efforts are not necessarily fake. They are, however, not real either. They are not real because the labor of becoming authentic requires cycles of self-observation, recognition, and transformation. Only, that last step tends to get blocked. It gets blocked when one’s own being becomes the role that one seeks to enact. And just in that moment when one is finally about to slip into the relief of being unconsciously real, one notices that one is doing a fine job, and the work starts over.

Hence the risky seduction of the kind of realist magic that Powers offers—an offering not so different from Morton’s. It is a seduction because, being backed by science, it does not cost us anything. Indeed, quite the opposite: it promises to break the cycle of severing and disembedding for us. Yet it is risky, because in its self-assurance—(“For all she knows, she’s the first creature in the expanding adventure of life who has ever glimpsed this small but certain thing that evolution is up to . . .”)—it unwittingly doubles down on that older, modernist paternalism.

In much of academic culture today there is a palpable desire for authenticity. This takes multiple forms. But across this multiplicity, there is a drive toward reembeddedness and the hope of reenchantment (Connolly 2013; Kohn 2015; cf. Smith 2013). This, I suspect, is an echo of a broader social fact: a reverberation of the widespread if inchoate longing to get beyond the wounds inflicted by modernity’s disenchantment.

The work of new materialists, like Morton, has given these longings forceful conceptual articulation. Though substantively diverse, these efforts are marked by a convergent sense of urgency: in the face of looming environmental disaster and the imperial machinery of late capitalism, the time is long overdue for scholars in the most privileged parts of the world to proliferate, and seek to inhabit, modes of knowing and being that hold out some hope of helping human and nonhuman others overcome the binds of being severed and disembedded.

This urgency has been embodied through a return to metaphysics. True to the delicacy and difficulty of the task at hand, this metaphysics is deliberately partial, tentative, open, processual, and keyed to a range—as Connolly puts it—“of nonhuman forcefields” (2013, 400).

New materialism seeks, in this way, to remain resolutely antidualist. That commitment to a more unified sense of the real constitutes, simultaneously, a refusal and a cultivation. A refusal of the tendency of North Atlantic culture to partition realness into opposing categories; the cultivation of a feel for the inherent liveliness of matter-energy complexes situated beyond those older tendencies and the troubles they bring.

All of this is haunted by a longing for a new authenticity—an unschooling of older imperial intellectual and political habits. That longing, at its best, takes form as a commitment to undertaking the work needed for disenchanted moderns to extend, enrich, or even abandon and replace inherited perceptual sensitivities.

The need for that subjectivational labor has been particularly pressing for ethnographers, for whom the shadow of colonialism remains palpably dark (Smith 2013; cf. Asad 2003). Ethnographers, after all, were among those whose job it was to authenticate the differences that sustained European superiority, not least the cut between reality and the real.

Ethnographers, alongside other postcolonial scholars, have sought to invert relations of power by exposing the way imperial norms remain implicit in received forms of knowledge production. This critical labor has been joined to a more properly decolonial imperative: it is not just about what to leave behind. It is about discovering what else might be imagined.

That creative and speculative aspiration brings the subjectivational challenge to the fore: to enter more deeply into the turbulent waters of what counts as real and for whom, those of us caught in games of authenticity and the real will need to transform our perceptual sensitivities.

As I noted at the outset, the form such work will take will need to be determined in relation to the local topologies within which scholars take up this work on themselves—the spaces and places of solidarity and belonging. But there is a long history of embodied exercises—equipment—that one might try out. This is not the place to enumerate and explore these exercises. But even a quick glance at more radical ethnographic experiments suggests possible directions: hold the hand of the dead, listen to stones, wrestle with demons, talk to trees, sleep with witches, walk through cities, maybe even pray to the gods (Ochoa 2010; Cohen 2015; Pandolfo 2018; Kohn 2013; Favret-Saada 1980; Certeau 1984).

Such transformative work is difficult under any circumstances. But it is difficult twice over for contemporary thinkers trying to embody antidualism while resisting an older politics of authentication (Orsi 2018). To make matters harder still, one must resist the temptation to think science can get us there after all. As B. points out about The Overstory, the proposition that somehow, someway, the sciences (of trees, of microbiomes, of quarks) have reenchanted the world tempts us into thinking that maybe good, disenchanted moderns need not change their perceptions of the real after all but just swap out liveliness for real presence.

All of which is a long way around of making a rather simple point. I do not think that one can take up the mandate to be decolonial without actively resisting the ghost of a paternalism that takes things like animism and vitalism to be forms of false consciousness. Said positively: to take up the mandate of the decolonial, I think one has to remain open to taking presence seriously.

But here again is that rub. For new materialists like Morton, the refusal of religion, and the unmasking of the retrograde effects of an otherworldly disposition, remain politically and ontologically nonnegotiable. But it is crucial to remember that alongside the figure of the overbearing cleric or the Christian bourgeoisie, the modern world remains full of grandmothers venerating shrines, pilgrims placating gods, and animists transforming into jaguars while their human bodies sleep. New materialism might be able to explain these experiences of presence. But only at the risk of explaining them away.

Whether and how such unseen beings might yet be included in the company of the symbiotic real remains to be seen. But giving up on the authority to authenticate others—or declare them inside or outside the bounds of respectable reason—might constitute a next step in the work on the self that extends not only perceptual sensitivities but might yet provide an exit from the purgatorial play of authenticity and the real. 5