Cannibalizing Architecture: Between Two Worlds

As an architect, I explore ancient construction methods that have faded into the distant echoes of prehistory. I define prehistory as any era when human endeavors have been lost, forgotten, or erased from written records. The sites I study are shrouded in mystery and veiled by the passage of time. There’s no paper trail, no source text, nor construction documents to provide clarity.

Because of this obscurity, these sites often become breeding grounds for contention, drawing speculative narratives attempting to explain their enigmatic origins. Whether these works were constructed two hundred or twenty thousand years ago, attempts to decipher their stories yield remarkably parallel theories. Recurring themes include crop circles, extraterrestrials, liquefaction, levitation, ancient technology, and unfounded suggestions of a forgotten race of white giants. The allure of unraveling their mysteries persists, transcending both time and geography.

My work navigates the uneasy divide between two distinct groups associated with these sites. On one side are the archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians, who prioritize tangible evidence and logical inquiry. On the other side are the mystics, speculators, and conspiracy theorists, who chase captivating narratives. Personally, I find evidential answers more astonishing than speculative theories, although I recognize that my perspective is shaped by a Western inclination toward rationalism. Consequently, I push myself to explore the possibilities within the irrational with equal vigor. This statement is likely to provoke ire from both camps.

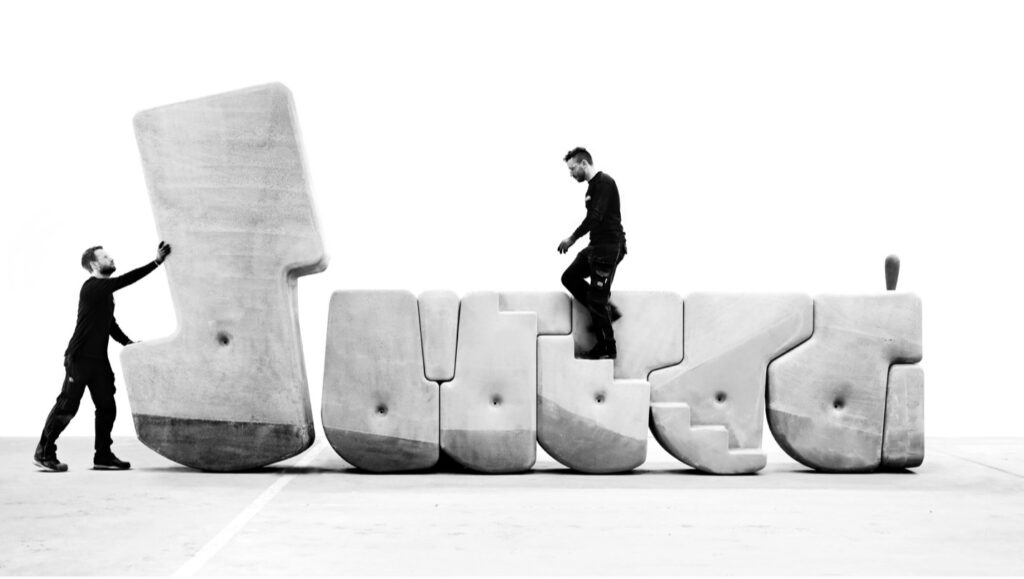

Because of this entrenched division, my work transcends the modernist divisions between science and spiritualism or between modernity and its alternatives. In line with Alfred North Whitehead’s rejection of bifurcating nature into physical and mental realms, I refuse to categorize ancient construction methods as purely factual or fictional. Instead, I embrace the tension between these interpretations, recognizing their intertwined complexities. While I am deeply curious about understanding historical events, my work doesn’t seek to confirm or refute anything about the past. Rather, it harnesses the interplay between factual and fictional interpretations to shed light on our future. By resurrecting abandoned construction methods and integrating them into contemporary practices, I confront the obsolescence of today’s construction practices. I move megaliths to reintegrate architecture with the processes of extraction, transportation, and placement (figure 1). I cannibalize demolition debris to challenge the false notion of permanence in our built environment (figure 2). Additionally, I align stones with celestial events to broaden the scope and timeline of architectural education, emphasizing the long-standing relationship between architecture and cosmic forces (figure 3).

In embracing the productive confusion surrounding prehistoric sites, I chart innovative paths for modern construction. By immersing myself in the dynamic interplay between fact and fiction, I navigate the complexities of both worlds simultaneously, seeking not just answers about the past but insights for the future of architecture. On one side, I delve into practical and applicable practices that have been deliberately removed from the historical record or forgotten over time. On the other side, I’m immersed in a realm of mystical speculation, wonder, and creativity, often accompanied by perplexed confusion and unjustified allegations of “primitive” practices, all viewed through the lens of today’s presumed cultural supremacy over prior civilizations. I’ve grown accustomed to this nebulous terrain and the range of possibilities its uncertainty generates. However, conveying the implications of these practices often encounters resistance in bridging the gap between these two worlds. This struggle is evident in my book The Cannibal’s Cookbook: Mining Myths of Cyclopean Constructions (2021) (figure 4).

This challenge first arose during discussions with potential publishers for the book. The Cannibal’s Cookbook defies easy classification as either fiction or nonfiction. Publishers were, understandably, uncertain about where to place the book within the binary categorization established by Western Enlightenment-era thinking. While the decision to blend genres did complicate the positioning of the book, the nebulous nature of the content also sparks the reader’s imagination. The primary obstacle was the choice to centralize the term “cannibalism” as a key theme and prominently feature it on the cover. I stand by this decision. It arouses curiosity. I’m convinced it’s the right term for the practice I’m uncovering. However, I admit that utilizing the loaded term—cannibalism—doesn’t necessarily provide immediate clarity to potential readers. The most frequent initial question I’m asked about the book, aside from humorous references to Hannibal Lecter, is “Why Cannibalism?” There are two converging reasons for this choice, mirroring the divergent realms of fact and fiction—practical and satirical.

Practical

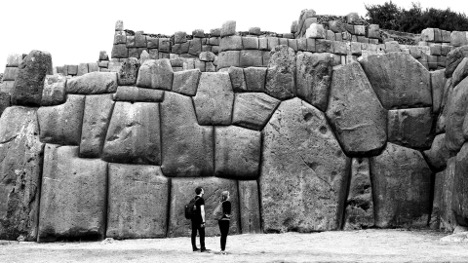

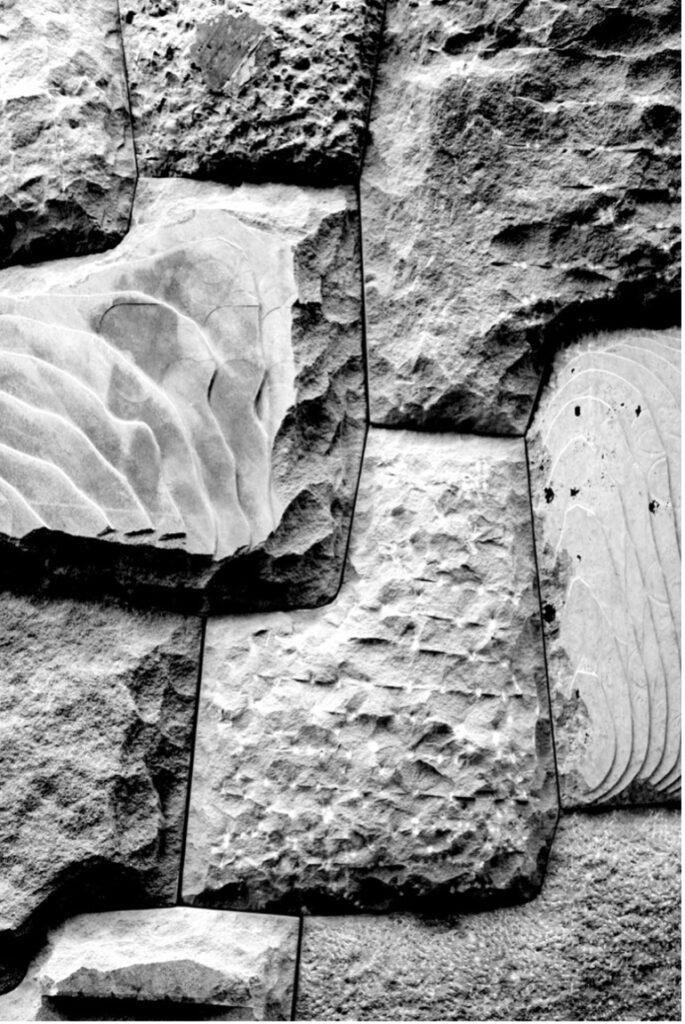

We’ve now entered the realm of rationalist thinking. Let me engage with this responsible community by making it clear: my use of the term “cannibalism” doesn’t in any way refer to the act of humans consuming human flesh. It’s not portraying prehistoric builders as flesh-eating savages. When I mention “cannibalism,” I’m addressing abandoned practices of buildings—not people—consuming the remnants of past defunct structures. For instance, in figure 5 we observe a polygonal masonry wall at Sacsayhuaman in Cusco, Peru. This serves as an illustration of how a shift in values can dramatically alter the outcome of building practices. Despite the enigmatic and puzzling appearance of these seemingly random stone arrangements to contemporary observers, it’s essential to grasp a crucial concept about these walls. The stones composing these walls were not extracted from quarries, and the structure’s elevations were not preplanned in the modern sense of design. Rather, these stones were carefully selected from loose rockfalls and repurposed (cannibalized) from previous structures.

Polygonal masonry is a subset of a rare building practice known as dry-stone masonry. In this technique, there is no mortar between the stones to fill and bridge gaps between elements. Consequently, these structures do not rely on chemical properties to bind the stones together; instead, they depend on the physical forces of gravity, the interlocking geometries of their shapes, and the sheer mass of the stones to interlock and secure each other in place. While the stones are carefully fit together, they are not permanently affixed, crucially allowing for disassembly and reassembly if necessary. Skilled artisans meticulously shape massive stones by using handheld hammer-stones, resulting in a mesmerizing tapestry of solid-rock behemoths seemingly fused into one another.

Polygonal masonry structures transcend mere relics of a megalithic era; they embody the architectural essence of a society committed to circular and sustainable building practices. Viewed through a lens less pragmatic and more poetic, these structures stand as timeless fragments, reincarnations of prior architectures.

In this context, The Cannibal’s Cookbook leverages this antithetical example to shed light on a concealed issue within contemporary building practices. It calls out the building industry for excessively filling landfills with debris, surpassing consumer culture by a factor of two. In an era that demands smarter practices, the modern building industry is addicted to new materials. Despite the greenwashing industries’ claims of “recycled content” in building materials, the solution isn’t merely reintegrating the intact remains of building rubble. The Cannibal’s Cookbook demonstrates ways to shift the industry’s focus away from constant newness by showcasing how past cultures ingeniously repurposed existing structures to create new ones, providing alternatives to today’s harmful practices.

So, why not just say “recycling”? Let’s take concrete, brick, and stone as examples. These materials make up the majority of demolition debris. Architects often specify new concrete to include a percentage of recycled content, a seemingly positive move. However, the reality isn’t as rosy.[/commentable]

Recycling concrete is far from sustainable. At this stage, a piece of concrete rubble is no different from stone or fired clay. It can contribute as a building element, bound by cement that combines sand, rocks, and other additives to form a resilient material capable of withstanding the massive compression loads of future buildings. Yet, recycling this intelligent material is more akin to a meat grinder than the appealing image of environmentally conscious practices.

Enormous machines, with gnashing teeth, voraciously consume fossil fuels as they chew and devour concrete, mercilessly obliterating its cementitious properties and leaving behind naught but a heap of sand. Worse yet, this sand is of significantly lower quality than that used in the initial casting. So, why would we endorse this dubious practice? The truth is, we don’t. There isn’t much demand for it. However, there’s a huge market for sending demolition debris to so-called recycling facilities, which then ship most of the rubble to landfills. This is the dirty secret of the contemporary building industry. Okay, so “recycling” isn’t the right term. How about “reuse” or “upcycle,” or the marketing-friendly term “circularity”? These are all undeniably positive terms. However, they fit neatly into a neoliberalized managerial vocabulary, emphasizing quantifiable outcomes. Yet, what I’m discussing implies a deeper epistemic shift, one that requires qualitative transformation and can embrace nonmodern belief systems. These buzz terms, while useful in some contexts, may not fully capture the complexity of what’s at stake here. Instead, I chose to embrace a pejorative term that directly combats the default vernacular of today’s middle management. When we confine ourselves to a narrow worldview that prioritizes positivity, efficiency, and quantifiable progress, we miss out on the possibilities of the other realm. The sites I study can’t be exclusively examined through metrics. Megalithic sites can’t be easily judged for their “efficiency.” Instead, there are intricate cultural practices, perspectives, motivations, and narratives intertwined with the success of these sites. While measurable actions struggle to drive climate action today, my work embraces mystical speculation—albeit through a satirical lens.

Satirical

You are correct. I deliberately chose the term “cannibalism” not solely for practical reasons but because it provokes an immediate reaction. I employ it to capture attention and shed light on the intricate histories woven into the megalithic stones I investigate. The rapid responses these stones trigger within modern Western society consistently captivate me. Often, the initial reaction is swift dismissal, accompanied by negative associations with the cultural practices that gave rise to these remarkable stone structures.

One commonly used angle to downplay the relevance of megalithic construction in contemporary times revolves around the aspect of labor. It’s important to acknowledge that these claims often stem from a sense of moral supremacy. They cloak themselves in utilitarianism, suggesting a lack of civilization in ancient societies. Accusations of unpaid and coerced labor are largely unsupported. Moreover, by assessing megalithic structures through a modernist lens of efficiency, focusing solely on the amount of energy and labor required to build them, we overlook the possibility that prior civilizations may have valued things differently.[/commentable]

Take the Inka as an example. The megalithic constructions of the Quechua culture were civic projects orchestrated by the ruling class, known as the Inka, as a form of tax payments. Communities would provide their best masons in the form of “tribute labor” to aid in the construction of infrastructural projects for the broader community. In one context, this would be viewed as a positive association between society and architecture. Construed another way, it suggests that the only way primitive civilizations were able to construct such marvels was through morally bankrupt, coercive behavior.

In the realm of myth and wonder, another enchanting explanation for these monumental stone structures often emerges. Some suggest that the sheer magnitude of these creations hints at an otherworldly origin beyond human capacity. Such assertions begin with a naïve but understandable question: “How could early humans, without the aid of advanced machinery, have possibly moved these massive stones?” However, I assure you, it was human hands that crafted these wonders. Nevertheless, the colossal stones provoke audacious attributions, ranging from theories of a lost white race to extraterrestrial intervention and historical hallucinations of primordial rock-chewing giants.

As mentioned previously, “polygonal masonry” is a technical and categorical term. Although the Inka were renowned for their mastery of this technique, it extends beyond their civilization. In the Mediterranean region, similar walls are colloquially referred to as “cyclopean masonry,” an homage to the mythical Cyclops. The implication is that only Cyclopes could have fashioned these enigmatic marvels. Just as polygonal masonry is not unique to the Inka, tales of ancient giants are not confined to the Mediterranean. Large stones, or megaliths, often inspire fanciful stories of bygone eras. In such dreamscapes, anything is possible. While these ideas are presented as whimsical and captivating, such misattributions deprive past civilizations of the credit they deserve for their architectural achievements.

Figure 7: The Cannibal’s Cookbook

Satirical

When the facade of utility and fantasy falls short in explaining these marvels, the Western mindset turns grim. A prevailing theme, particularly among the heirs of the Enlightenment, is to insinuate that civilizations constructing these megalithic marvels engaged in reprehensible acts. Even structures like Sun and Moon temples, revered as celestial observatories, are often portrayed as containing altars for human sacrifices. Such interpretations arise from the Western imagination. However, when explanations begin to falter, the ultimate insult—cannibalism—is tossed into the mix.

When Western explorers encountered the colossal structures built by the Inka and other megalithic civilizations, accusations of cannibalism arose. The irony of these claims goes beyond mere construction practices; it is embedded in the history of these Roman Catholic explorers themselves—their own culture both absorbed and subsequently weaponized such accusations. In ancient Rome, Christians faced similar charges, being labeled as cannibals because of their sacred practice of consuming the flesh and blood of Christ. Centuries later, Christian explorers perpetuated this pattern, this time in pursuit of their shortsighted conquests, disregarding the potential significance of such building practices and adversely impacting both humanity and the very climate that sustains us.

Conclusion

I consciously adopted the pejorative use of “cannibalism” to emphasize the intricate histories enveloping the stones I study. This deliberate linguistic choice serves as a potent form of satire, a tool I wield to illuminate and challenge the default practices of architecture today.

By intentionally harnessing the provocative nature of the term “cannibalism,” I invite readers to journey beyond the superficial and delve into the nuanced narratives that these ancient stones hold. The word acts as a doorway to the past, albeit a door that swings open onto unexpected vistas of introspection. This calculated move is not about sensationalism but about tapping into the power of language to provoke thought and contemplation.

In adopting the audacious notion that these stone marvels—archetypes of sustainable construction practices— could not have been crafted by early humans, I am underscoring the preposterous nature of contemporary building methods. This conceptual twist serves as a mirror, reflecting the often absurdly wasteful and resource-draining nature of today’s construction practices.

WE ARE THE SAVAGES. We are the ones with the primal rock-chewing behemoths that devour construction materials, digesting intelligent concrete only to leave behind a trail of sand in our wake. I leverage this metaphor to spotlight the incongruence between our self-proclaimed advancement and the regressive environmental impact we perpetuate. Our voracious appetite for resources results in the heedless consumption of construction materials. The intelligent concrete we erect is not immortal. It does have a lifespan. Upon recognizing this reality, we should broaden our perception to embrace the interpretations that blur the boundaries between the living and the nonliving.

The irony lies in our society’s paradoxical relationship with consumption. We revel in material abundance yet recoil when confronted with the implications of our actions—an irony that reverberates when faced with the sophisticated concept of “cannibalism.” This metaphorical exploration elucidates the intricacies of human behavior, the dissonance between our aspirations and our actions. It invites us to recognize the irony inherent in a society that champions progress while perpetuating practices that echo the primitive.

In weaving together the threads of satire, metaphor, and commentary, I present not a mere dichotomy but a synthesis of past and present. Through “cannibalism,” I endeavor to unravel the fabric of complacency, urging us to contemplate our own role as stewards of Earth. This linguistic device, this unconventional lens, challenges us to grapple with the ghosts of our construction past and reimagine our architectural future.

Ultimately, the journey into the depths of the pejorative “cannibalism” is a journey into our collective psyche, an exploration of the narratives that shape our perceptions and decisions. As I bridge the gap between ancient ingenuity and contemporary construction, I invite you, the reader, to embark on this voyage of contemplation—a voyage that beckons us to navigate the tumultuous seas of our own progress and confront the revelations they bring.