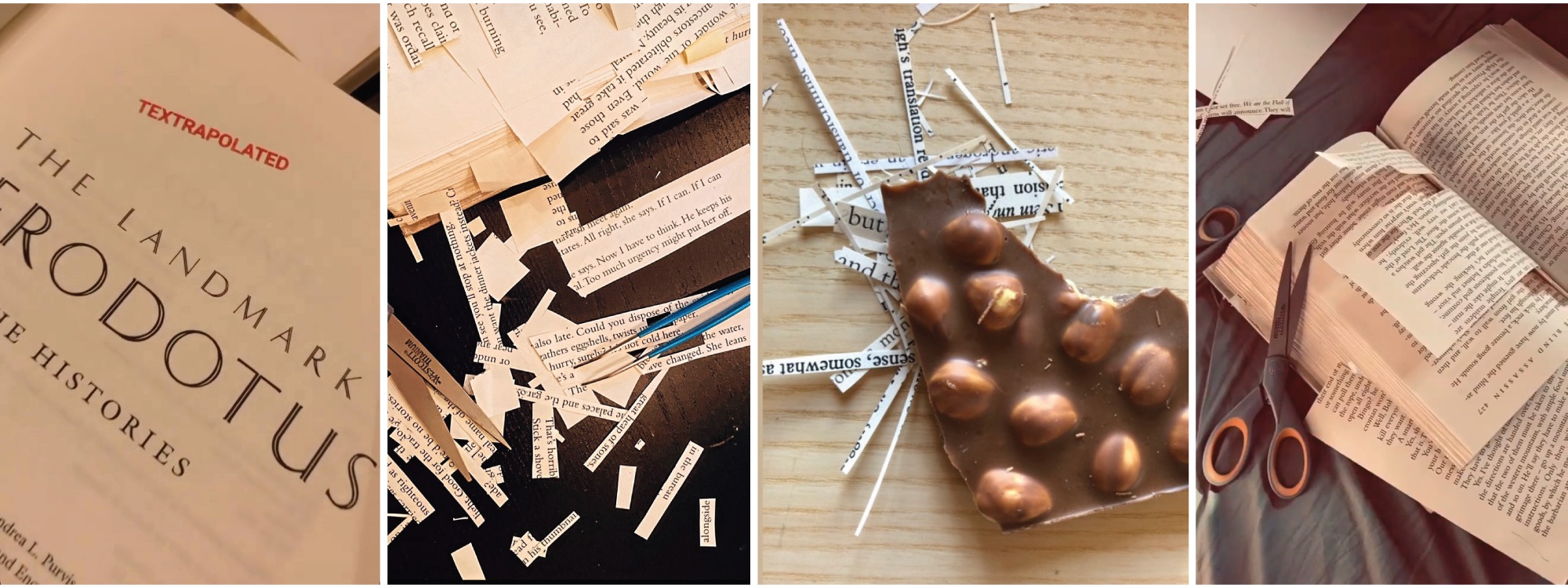

Cutting Up Books: Cannibalism as Design

Most people read books. I butcher them. Literally.

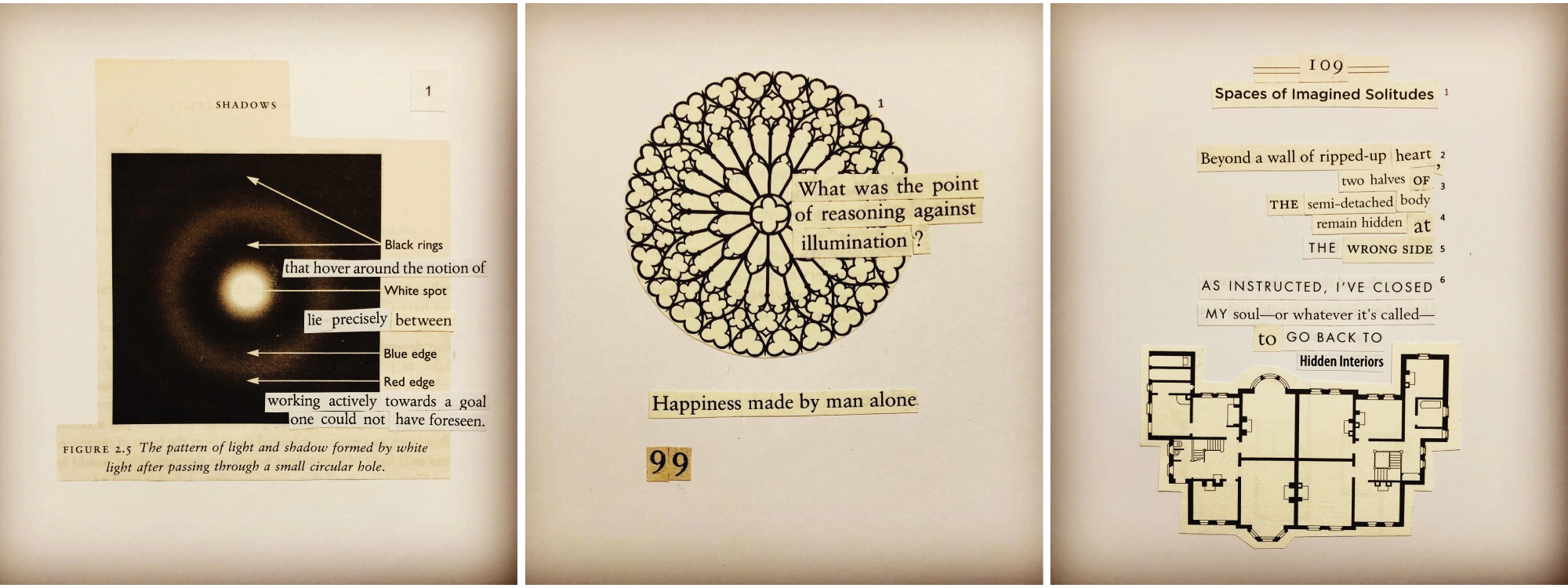

To be specific, I cut them up (with precision and force) and then reshuffle, reassemble, and prepare the cutouts for a “feast,” tentatively called textrapolation. As a perfectly cannibalistic act, textrapolation (i.e., extrapolation from text) is inundated with blood, even if shed only figuratively. Like most examples of cannibalism, textrapolation violates the limits of commonplace decency; it also offends sanctities (the book is a sacred thing, no?). The aim of such blasphemy is to disorient the cultural signifiers of a book object and show the limitations of book design. The book is not a cover-to-cover volume; rather, it is a tissue of meanings to prey on.

In what follows, I describe and discuss cutting up books as cannibalism and cannibalism as design. I do it in relation to a tradition of voracious creative reading and writing and to a personal project carried out three years ago for a period of six months, during which I cut up over six hundred volumes of human intellectual heritage and turned them into one hundred and eleven assembled poetic paradigms. Considering the book “a body” or “a machine to think with” (Richards 1926, 1), a “simultaneously sequential and random access device” (Kirschenbaum 2008, np), and “a spiritual instrument” (Mallarmé 2014, 68), I examine the flesh of the book and the mutilation of the sacred (the untouchable) that the book object invariably represents. I also dwell on cannibalistic kinesis: cutting, dismantling, skinning, and seasoning to examine the aesthetics of pathological urges and cravings in broad cultural and creative contexts.

Cannibalism in the Books

The book is designed to be devoured. It is also designed to be brutalized. Both those intents (or designs) serve the same purpose: satisfaction of hunger and a need for life-giving nutrients. Many people say they “cannot live without books” (cf. Jefferson 1830, 263). Many also say that books are a feast. Those alimentary metaphors get instilled in us very early. They usually start with the cultivation of the appetite for reading (that nourishes our minds) and continue with the design of book objects—the most literal rendition has been the book lunch box for children.

That same design dictates a certain way of conduct. Learning to crave books always involves learning to behave around them (just like we learn to behave around food). That behavior goes by specific rules. Most of those rules relate to the flesh of the book and mean to prevent the flesh’s violation. Dog ears, highlights, pencil marks, margin notes, page folds or rips—are all considered profane and unpardonable. Dada experiments with newspaper cutouts back in the 1920s (and onwards) were tolerated only due to the fleeting nature of a newspaper (an object trashy by default, meant for short-livedness and apt for destruction). But when a book is dissected, even the proverbial “for art’s sake” does not suffice.

In 2005, artist Brian Dettmer started an interesting (and perfectly blasphemous) cutout series dubbed Book Autopsies (Sliced Book Sculptures). The series lives on and develops further under many names and formats to be admired in gallery spaces or the artist’s studio in Chicago. In his website entry from the beginning of this project, Dettmer explains his rationales for book dissections and the dissection method. He says:

"In this work I begin with an existing book and seal its edges, creating an enclosed vessel full of unearthed potential. I cut into the cover of the books and dissect through it from the front. I work with knives, tweezers and other surgical tools to carve one page at a time, exposing each page while cutting around ideas and images of interest. Nothing inside the books is relocated or implanted, only removed. Images and ideas are revealed to expose a book’s hidden, fragmented memory. The completed pieces expose new relationships of a book’s internal elements exactly where they have been since their original conception. "

Cutting up books is threefold transformative. First, it brings out new content from the existing form. Second, it parses the content, leaving only the most edible parts. Third, it changes the entire culture around the dissected object, especially its somantics (somatic semantics) and intersthetics (interactive aesthetics). Also, the book already carries a cannibalistic potential—it invites destructive urges. Dissected books no longer consort to the limits of touch and contemplation; rather, they assume a brutally violent relationality: that of dismemberment and desecration.

My own book dissections followed the same intentional triad that Dettmer’s work did—only with a different technique. Instead of sculpture, I used collage. Also (but unlike Dettmer), I migrated the cutouts across volumes, removing the bits and bites from the books (and from the pages) to then regroup them together along the epigram’s organizing idea (a recipe, of sorts). The procedure was simple: I savaged a few random books, flicked through the pages, hunted the organizing idea between the lines, and butchered it out of the volumes. The process overarched one dilemma: “which of them [the books] shall die to furnish the food for all,” to appropriate Mark Twain’s famous line (2005, 14).[/commentable]

Whereas Dettmer’s preoccupation is with the core of the book, mine was with the leftovers (which in the process became an essence). Not that I compare those works. I simply use Dettmer’s art as a point of reference to build an argument about the imperative of violating the sacred (that books invariably represent). I also use it to build my point on cannibalism.

I never thought of cutting up books as a cannibalistic act. At least not until cultural criticism inspired that association. Analogies between those two astonish with accuracy. Maggie Kilgour, who started building them in relation to cannibalism and literature, was the first to theorize cannibalism in terms of cultural metaphors. Defined by her as an act capable of “dissolving the structure it appears to produce” (1990, 4), cannibalism gains respect for its role in reorganizing and restructuring the social milieus, especially the habitus (the structure or cultural environment that cannibalism navigates) and the habitus’s actors. Whereas dominant Western culture associates cannibalism with a split into the civilized, behaved world and the savage and barbarian one, cultural interpretations of “the West” see cannibalism in terms of a split within the civilized self. When threatened, stuck, or otherwise oppressed (even if only symbolically), that self remembers the savage in itself.

In the literal sense, cannibalism is humans eating other humans’ flesh (or body parts). In an ethical sense, it represents human’s most repulsive tendencies. Approached critically, it brings together the deepest taboos and the strictest moral codes. At the crossroads of those conjunctions lies a transformative potential. By feeding off the flesh of their own kin, people have always sought a panacea—and a passage. All types of cannibalistic practices—from rituals (like eating the parts of the deceased) to judiciary (like vengeance) to medicine (like drinking potions of powdered bones) to survival (like trying to outlive a catastrophe: plane crash) to cuisine (like cooking human parts and organs for culinary purposes in Yuan Dynasty China)—carry within them despair for a solution (or transcendence). They are all tinted with a creative urge and a motivation to test the limits that may take them beyond what is and what no longer serves their purpose. And creativity always atones for violence.

However used, cannibalism is not about the act it represents. Or put in Peggy Reeves Sanday’s words, it “is never just about eating.” Cannibalism, she claims, “is primarily a medium for nongustatory messages—messages having to do with the maintenance, regeneration, and in some cases, the foundation of the cultural order” (1986, 3). Anthropological discussion on cannibalism rests on paradigms that tend to excuse the violence of the cannibalistic act in favor of its creative motivations. Psychoanalytical approaches see it as variants of a sexual desire; pragmatic approaches explain it in terms of adaptive methods. Hermeneutics pertains to “the broader logic of life, death and reproduction” (Sanday 1986, 3). All of them rely on a human fantasy of cannibalism that Mark Buchan (2001) associates with “the ethics of anger”: instinctual urge vis-à-vis its curated repression. Some anthropologists believe that cannibalism does not exist as long as it exists in everybody. In this sense, the assumption “we have never been modern” (Latour 1991) conjectures that we have never got rid of our intrinsic cannibalism.

Whichever of those interpretations works best, they all agree on the situational and culturally driven motivations of the cannibalistic act. Kristen Guest outlines it with an emphasis on meaning formation and the act’s signifying (or perhaps) resignifying function:

"Cannibalism is now widely viewed as a complex, diverse cultural practice whose meaning is determined by the sociohistorical contexts in which it is practised rather than through a preset “universal” pattern. [It] enabl[es] the production of meanings and values within a particular social system, [and] in Slavoj Žižek’s words, “a kind of reality whose ontological consistency implies a certain non-knowledge of its participants.” [ . . . ] Cannibalism draws our attention to the problematic relationship between real acts and the imaginary structures available to make them meaningful. [ . . . ] The discourse of cannibalism invites us to reflect on how the construction of difference is always limited by the sociohistorical context in which it is produced. Thus, as a critical figure the cannibal does not just call into question the universality of binary structures that generate meaning, it also [ . . . ] challenges us to stop thinking of the coexistence of what we call humanity and savagery. " (2001, 4)

Cannibalism and cutting up books share the same kind of pining for transcendence. They also share the same penchant for blasphemy and a certain form of lunacy oblivious to the domineering common sense. There is something about cutting up books that is out of (the) mind. Books are multilayered reservoirs of universal logic limited by a form. Cutting opens them to limitless consummation and unconstrained metabolism.

Cutting up books is ecstatic. It feels more real, more authentic, and more satisfying than any other kind of writing. It satiates the deep hunger for self-expression and articulation. It is almost as if what you “wrote” (and how you “wrote” it) came from the guts (and not from the brain). No wonder cut-up techniques are often associated with intuitive arts—just like cannibalism is associated with intuitive cuisine. The non-knowledge, by which Žižek means ignorance of the proper logic, functions here as the ignorance of the meanings attributed to things and their use. We cannot cannibalize as long as we do not forget the cultural signification of the body and a person and humanity as kin. The same works for cutting up books—possible only when we forget what a book is, how it came to be, and how it is supposed to be used.

Book Dead Tissue

The book has been considered a powerful object. Almost visceral. Although its corporeality is rather metaphoric, history discloses links between a book object and organic flesh featured in the object’s evolution towards its current form. According to historical accounts, dead tissue has been a part of book design since the emergence of parchment (1500 BC). Even though parchment is no longer in use (except for the rare instances of leather book covers, whose material is now being replaced with artificially produced textiles), it brings back the book’s bodily relations and corporeal facts. Keith Houston’s history of the book object considers parchment “the grisly invention.” It also paints a pretty cannibalistic portrait of its production:

"Having soaked and unhaired a skin, the Pergamenes discovered that by stretching it on a frame and allowing it to dry before cutting it down, the skin could be made to maintain its tautness and resilience. In mammals the dermis, the middle layer of skin from which leather and parchment are made, is composed of a network of minute collagen fibres. As an unhaired skin soaks in its preparation vat, these fibers absorb and become saturated with the bath’s liquid, and this, in turn, mingles with the skin’s own secretion to suffuse it with a sticky adhesive fluid. Stretching the skin causes some it its fibers to break while others are pulled tight, aligning with the plane of the skin, and as the realigned fibers dry out they cause the skin to set in place. [ . . . ] The result [ . . . ] is a taut, flexible material. Whereas leather is soft and limp, a sheet of parchment flexed gently across its surface readily springs back to its original shape [ . . . ]. Moreover, parchment was stronger than papyrus: a skin gashed by a careless tanner’s knife could be safely sewn up [ . . . ] without danger of tearing. " (2016, np, Kindle)

This evocative passage reads in many ways exactly like the culinary descriptions of the human flesh. In certain geographies, human flesh has been considered a delicacy superior to other kinds of meat only due to its material properties (just like books in cut-out art). Transforming that flesh into food entails “special” and specific procedures aimed to appropriate it for a meal. Such appropriation relies on eliminating the human element; just like the appropriation of the skin for parchment relied on eliminating the organic trace (without losing its properties). Books have been figuratively called “the food for thought.” It seems like the idiom renders the nourishing aspect without metaphors.

Today, the book is a carry-on storage of information that serves the cultural exchange (Borsuk 2018, 1). It is also a distribution device trying to reinvent itself by means of digital advancement. That reinvention invites new cannibalistic metaphors—those of the “death of the book.” A new postmodern myth, the death of the book pertains to the alterations of writing and reading as they leave the traditional “codex” to dwell in the modern-day e-book readers wired to unlimited data. Hypertext was the first implication of the formulaic obsoleteness of a book volume, long before Kindle culture brought the paperbacks down by nearly 40 percent. The idea of limited content versus unlimited text in a networked environment took over the isolated (and tedious) cross-referencing. Despite the implied diversity of the book culture, the book’s claustrophobic form heralded its stagnation. The question was how to metabolize that form into a renaissance.

Dissatisfaction with a book object predates the digital revolution. In fact, it developed alongside the mass printing industry whose explosion was witnessed in the 1870s, with a notable spike through the late twentieth century. French poet Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898) believed that the book was a spectacle of matter. Such an approach invited experimentation, especially with traditional layout (see Mallarmé 2018) and other book-related decorum. In 1920, one of the notable members of the Dada movement, Tristan Tzara, suggested a recipe for a perfect poem, leaving its composition to destruction and serendipity. According to Tzara, a poem should emerge from a contingent permutation of words removed from their printed environment by means of a cutout technique and exist away from the traditional volume. Tzara’s instruction goes as follows:

"Take a newspaper. Take some scissors. Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem. Cut out the article. Next, carefully cut out each of the words that make this article and put them all in a bag. Shake gently. Next. Take out each cutting one after the other. Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag. The poem will resemble you. And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd. " (Tzara 1963, 39)

A similar formula by Brion Gysin radicalized Tzara’s approach by extending it to other printed forms. It says:

"Pick a book any book cut it up / cut it up / prose poems / newspaper / magazines / the bible . . . slice down the middle dice into sections / according to taste . . . taste it like piping hot . . . piece together a masterpiece a week . . . the writing machine is for everybody. " (Gysin 2015, 73–74)

Alex Danchev aptly observes that “the figure of the cannibalist seems to have exercised the avant-guard movement” (2011, 219). It now exercises postmodern minds, even more so and to greater degree. Following Tzara, Gysin, Burroughs, and Acker, a new generation of book butchers take the cut-out technique to another level. (Next to Dettmer) Nicholas Jones, an Australian book sculptor dubbed bibliopath, questions the future of the written word by carving, tearing, cutting, folding, sewing, and otherwise transforming books in ways that retransplant the Dada book imagery with advanced precision: “Like a surgeon examining and reorganizing body tissue, armed with a scalpel, Jones readdresses the book’s tissue—paper—dissecting unwanted books, casting a new light on books as an everyday commodity” (Onderwater 2011, 209). This is exactly what the new generation of book cannibalism is preoccupied with: the tissue.

Cannibalistic Design

The cutting-up techniques I am describing here pertain to what some cultural theorists call “cannibalistic design.” Cannibalistic design takes place when aesthetics eat one another and when they look back to speculate about the future. Burroughs considered cut-ups to be a form of divination. Oswald de Andrade—proponent of cannibalistic design—considered divination to be a conjunction of traditions from which speculation designs the future towards its most veracious form. In his “Cannibalist Manifesto” (1928), a piece revisiting the decline of original cultures (in this instance, the Brazilian one), de Andrade juxtaposes progressive (modern) and native (cannibalistic) modes of living to negotiate cultural aesthetics vis-à-vis cultural refinement. The latter has long considered the barbarian uncultured enough to almost completely eradicate it from the cultural practice. From that (de Andrade implies), disenchantment and depression followed, and we got separated from the healthy and spontaneous gestures with which we had navigated the non-limits of our creative experience in relation to the experience of life. That creative experience, before it was cultured (and refined), had meant fluid relations between people, objects, and meanings. That fluidity relates specifically to the code of conduct around objects that was essentially codeless and inessentially organic. De Andrade’s invitation to cannibalism is similar to Agamben’s later appeal on the priority of bare life: a life in which a fact of life determines the way life is lived. A “re-instalment” of such a condition would mean a (re)turn to, and (re)invention of, many operational potentialities. For this to happen, we would have to unlearn the colonized style of living (and creativity) and cannibalize the refinement of our modern existence. We would also have to adopt an unobscured awareness of the refinement of savagery and the savagery of the refined and live it beyond dualisms, encouraging a fusion of inspirations, manners, approaches, and styles synonymous with the cannibalistic primitive—organic, intuitive, instinctual—all-encompassing-ness. As de Andrade explains,

"Cannibalism alone unites us. Socially. Economically. Philosophically. We already had justice, the codification of vengeance. Science, the codification of Magic. Cannibalism. The permanent transformation of Tabu into a totem—down with the reversible world, and against objectified ideas. Cadaverized. Death and life of all hypotheses [ . . . ] Subsistence. Experience. Cannibalism." (1991, 38, 40)

The spirit of de Andrade’s manifesto lives on in modern design. One of design’s major focuses is to decolonize—that is, to cannibalize anew—the concepts of construction and creative expression. A notable point in this regard is made in Brandon Clifford’s work on the cannibalistic architecture presented in The Cannibal’s Cookbook: Mining Myths of Cyclopean Constructions (2021). A manifesto in its own right, this book revisits the primitive ways of organizing the landscape, or, to be specific, the modern-day Lebensraum, for sustainable design and better living. Lamenting the “concrete” solutions in refined architecture, The Cannibal’s Cookbook points out the changes indispensable for a livable future and draws from the past to implement the future’s premise. Part primer, part glossary, part practical guide, this book offers a journey across the ancient construction methods that seem to outsmart our contemporary materials, solutions, and the understanding of a building as a thing. That thing is now a victim of constructional obsolescence and a cause of environmental devastation. More importantly, however, it compromises civilized approaches which have lost touch with their own thing in the pursuit of novelty and upgrade. The book amends this loss by recycling architectural cannibalism of old age in a meta-criticism that reclaims the reuse of nonreusable materials (e.g., rubble). Cannibalism is viewed here as “the process of buildings eating other buildings in an upcycling of matter” in “cities [that] live in a permanent concrete hangover [and] binge . . . inhale behemoth quantities of concrete and steel . . . purge . . . eliminate any structures that stand on their way” (Clifford 2011, 183, 25). Cannibalistic architecture would then be “a situational architecture. One that is utterly non-deterministic, malleable [and] confronted with possibility, and the immediacy of formal response, [architecture] that flexes and slackens, that responds to what is right in front of it” (23). Without dogmas and constraints.

Cannibalistic design is implied here as a healthy diet of social organization. Like the Oswaldian cannibalistic utopia, it (re)installs the ecumenic appropriation of things: objects, bodies, ideas, and activities, and ensures their unappropriated coexistence based on “experimentation,” free access, and upcycle. Such coexistence is complementary (rather than eliminatory) and transformative insofar as it is capable to stay raw and fresh.

Cannibalism seems to be a key metaphor to interpret and revisit contemporary cultural practice (as a whole) in this pivotal moment of technological confusion wherein renovation and innovation have been the slogans for “growth” and development (the civilized). It makes good use of the cultural chaos and its hybridity of forms, species, tendencies, etc. that, like organs without a body, invite consummation and recycling. In this way, cannibalism steps away from its metaphoric context and becomes a way of life. This is the way of free design in which cannibalism stands for the consumption and metabolization of all those “bodiless organs”—organic, technological, cosmic—that transcend the current signification of things by eating, chewing, and spitting them out—transformed yet contained.

In “Design Livre: Cannibalistic Interaction Design,” Fredric van Amstel, C.A. Vassão, and G.B. Ferraz explain this transformed containment (or contained transformation) with regard to the free software Design Livre, aimed at integrating cultural complexity and cosmopolitanism in contemporary Brazil. They term cannibalism a festive celebration of old and new forms enabled by embodied relationships:

"When ideas and technologies are part of human bodies, they become alive and develop further. If they are not used, they die. Design Livre proposes that cannibalism should be encouraged—instead of prohibited—in design practice and education, in an attempt to give an after-life for projects. When practiced with the same honor that Brazilian Aboriginals dedicated to their eaten enemies, cannibalism can foster collaborative environments, where everyone profits from working together. It legitimates copy and plagiarism, which were so important for recent innovations in arts and technology development (Critical Art Essemble, 1994). As we create this post-humanist reality, we should keep in mind that “we stand in the shoulder of giants,” as Linus Torvalds once explained the success of the Linux Free Software Operating System, a phrase repeated by many other important figures across the last millennium, each in a different cultural situation, each with a different meaning, but all of them with the same appreciation for the Other. " (2011, 454)

The inclusive reciprocity of cannibalistic design is undoubtedly its key virtue. Another is its universality. To paraphrase Burroughs, cannibalism as design is for everyone. Anybody can cannibalize. Cannibalism is nothing you discuss but act upon: cannibalism as design is something you do and put into action. In fact, all real design is and should be cannibalistic. This, I guess, answers the problem of future creativity. Whatever writing, painting, teaching, constructing, etc. carry into the future, it should contain the cannibalistic urge. As a solution, cannibalism is affirmative. Cannibalism as design means destruction for renewal.