Hard Borders/Soft Disciplines/Gonzo Actions: Gonzo, Borders, the Unqualified, and the Equivocal

"Gonzo, also known as The Great Gonzo or Gonzo the Great, is a Muppet character known for his eccentric passion for stunt performance. Aside from his trademark enthusiasm for performance art, another defining trait of Gonzo is the ambiguity of his species [. . . ] Gonzo [the Great] was created as a character with low self-esteem, as written by Jerry Juhl, with [puppeteer] Goelz acknowledging he put himself into that interpretation. Later, with Jim Henson’s approval, they reworked the eyes to allow the character to convey more excitement, and a 'zany, bombastic appreciation for life.'" —“Gonzo (Muppet),” Wikipedia, last modified October 25, 2021

Prelude

Gonzo reentered my life through a casual and probably erroneous reference to my fiddling with documentary journalism. Hunter S. Thompson’s time at the races in a dust bowl, trying to report on something that was impossible to see, initiated the new genre of “gonzo journalism.” The application of that reference to my work was perhaps based on my being in another kind of “bowl,” the dust bowl of the Calais Jungle, where to see and document the “truth” of the situation was impossible, and a limited vision was all that I had to view and attempt to comprehend a chaotic situation. Later, whilst checking up on Hunter in Wikipedia to see if there was any shred of connection between what I was doing and what Hunter S. Thompson did, I was immediately distracted by Gonzo from the Muppets: a cherished character from my childhood who, unlike Thompson, I felt I knew pretty well.

Gonzo began to represent a state for design. Or, perhaps, even a new design practice? A state of readiness to fail fast and try again, to follow a hunch or try a new way. Gonzo displays a state of being for any creative practice. His “bombasity” can be a positive attribute, if it convinces one of something new or introduces another way, another path, another approach to a practice. “The Gonzo”: the nonexpert, the in-betweener, the disciplinarily restless and unprofessional fidgeter. Gonzo is not unlike the “Idiot” in Deleuze’s sense, who meanders through a practice and doesn’t take “what everyone knows” for granted; unusual questions and approaches, and, as in Gonzo’s case, spectacular results take shape.

Is Gonzo great? I think I’ve convinced myself Gonzo is great—really great. He’s not confined by “under-ambition,” disciplinary logics, or borders and will attempt to hold a piano on his finger on a tightrope and do multiplication. The things he does, he does not do particularly well, but the magic, the sweet spot, the opportunity, might be in the ill-advised combinations of things.

“Gonzo ambiguity” is something that suits me well, as someone who has never been comfortable declaring disciplinary astuteness. Maybe, using Gonzo, I’m validating a/my position as a nonacademic, as unproven and nonrigorous, an unprofessionally ambiguous meanderer. Thinking further about Gonzo the Great and his being committed to being noncommittal, his(?) nonspecificity is the space of opportunity. His magic happens at the convergence of interests; he’s neither this side nor that side of the border; rather, he is the border: he’s both/and, never either/or.

Gonzo’s attribute of bombasity is something that most of us don’t experience in our day jobs. The mechanics of 24/7 capitalism perhaps force us to become measured, calculated, professional, and boring. Gonzo is not professional, but he has to be convincing, at least sometimes, to himself and others. He is para-, ecto-, interprofessional. Gonzo’s eyes widen because he is not an expert, because he’s keen to have the skills or inhabit the territory of others. But because he’s keen, he’ll take shortcuts with training, he may miss out on really critical parts, he may also miss out on the uncritical parts. Somehow, being in the space is more than enough. Questions and shortcuts will emerge, some dumb, some not. It’s when we converse across professions, and gain interest in the professions of others and even regain an interest in our own, that we realize our own disciplines just needed something from outside that went missing.

Gonzo’s eyes widen because he is excited and nervous in equal measure. Existing in terra un-firma can do that.

Bombasity might occur in the gap or the space in between, in the desire to find similarities and possibilities. The heady dialogue of the possible. Is this the operating landscape of Gonzo the Great? Would Deleuze and Gonzo get along? I know more about Gonzo than Deleuze, but from what I’ve heard, I think they’d enjoy each other’s company. I think they’d engage and try hard to understand the other despite their differences . . . they’d discuss these gaps and find common interests in the foggy spaces between.

“Gonzo spirit”: the ill-thought mashups that feel important or might do something unexpected. Gonzo might have got Deleuze to do an interdisciplinary performance piece or try acting in a movie. Deleuze may have convinced Gonzo to try singing philosophy whilst jumping on a trampoline and flipping pancakes. Ahh, what a show!

So I obviously have developed a weird crush on Gonzo. I’ve forged a connection with a ’70s puppet. It could be low esteem; a result of being a professionless practitioner. Perhaps I connect with Gonzo because it’s a way to declare my own skill-lessness before anyone else does. Though more often than not, what Gonzo does is shaky, clunky, wobbly; everything is still to be attempted. Maybe Gonzo is who I want to be. Another in a long list of my spiritual guides! Maybe in an age of specialism, Gonzo’s attributes of transdisciplinarity and bombasity are something to be celebrated and protected.

Crisis

Around 2012, the work James Auger and I had been doing was increasingly shown in galleries, which was pulling us away from our ideas about “expanded audiences” that we explored and pushed in new directions in our piece Audio Tooth Implant. Early intentions of using the press as a conduit for our ideas and questioning the tech tornado, rather than promoting our work in niche settings, were slipping away. And by 2012, I was wondering if we had been “exploring the implications of technology” for too long.

Whilst getting ready to present some work called Carnivorous Domestic Entertainment Robots at a conference in Amsterdam, I heard Cameron Sinclair talking about Architecture for Humanity and the amazing organization Skateistan, founded by Oliver Percovich. I was about to go on stage and talk about a series of domestic robots that ate flies and also told time. Precisely at that moment, a “practice crisis” began. And as I trudged onto the stage, I thought to myself, “Stupid Fucking Robots!” After a slightly flat talk, I waited for some mud to be slung from the audience, but no one threw any. Speculative design or I or both had lost some novelty and ability to provoke. “Stupid Fucking Robots!”

Cameron Sinclair, on the other hand, felt and was engaged with the “real world”; he was relevant, positive, and powerful. Despite this mini-crisis, my Gonzo eyes widened, I felt bombastic and inspired, and another concerted effort to make a shift in practice began right there.

James was doing his PhD, something I was annoyed about for some reason or another, probably jealousy. In response to his rigorous pursuit and focus on design, I declared myself, quite childishly, unrigorous, subacademic, and a subdogmatist. I scorned Derrida and Descartes for no reason and became a kind of dumb antitheorist. Looking back, there’s no pride in that, and it’s maybe why I’m talking about Gonzo the Great instead of great human thinkers.

All the Camerons

Cameron Sinclair became an embodied conscience, living in my head and telling me that I wasn’t doing enough or even doing anything. It hit me hard, realizing I was making fake robots that ate insects and he was doing “architecture for humanity.”

I even agreed with the ever-grumbling Cameron Tonkinwise, who took residence in my head too. He hated all fiction, speculative things, and everything I’d ever done. His eyes seemed to bleed from weighty theory carried around in plastic bags, and all that reading pointed to me as being responsible for all that was wrong with design and the world. We, the speculative and critical designers, were viewed as delinquent designers and accused of a dereliction of professional duty. In my defense, by learning and experimenting with other means of production, I/we were just trying to avoid becoming another cog in the endless production of tech junk furnishing the capitalist endgame. And, of course, it was flawed in lots of ways.

At times, I’ve felt pretty irritated with Cameron Tonkinwise for his criticism of speculative or critical design and the people who were protagonists in a huge change in design education. Many of us swerved away from the lure of more traditional design jobs to try and explore different paths, to see if there was a way for designers to operate reflectively. Other disciplines can do that: fine art, philosophy, poetry, music. British governments seem intent on smashing all that up, with STEM subjects taking priority and risky creative trajectories being priced out of the game as the UK is seemingly giving up on culture.

I wanted to save humanity too. I yearned to contact Cameron Sinclair and plead for a job as an intern. I knew it would be in vain, as he’d already declared that he would only work with real architects and had dismissed “paper architects” as not real architects in his talk. I had the unwanted badge of “speculative designer,” which he would probably dismiss as even worse. I assumed Cameron Sinclair would hate me, laugh in my face. And though I’d never intended to be a speculative designer, he would have called me one; Cameron Tonkinwise had probably already called him and told him not to give me a job. To complete the band of Camerons messing with my head, David Cameron was elected and attacking higher education, specifically the creative subjects.

I was taking this really fucking personally. I was under attack from all the Camerons.

David Cameron, with his catastrophic political dithering, was accidently fanning the flames of Brexit, describing refugees as “swarms” and planning a referendum on Brexit and ultimately getting ready to bail out from a huge multigenerational mess he was creating. For me, and many others these days, being British is just embarrassing.

Borders

A border is a strange place, somehow meaningless but given meaning through time, law, and definition. What is achieved by borders? What’s protected by them? Why are they so fiercely disputed or guarded? The coveting of land, of culture, of sovereignty? Or is it the space where we just stop caring or care too much? What or where we want enough and where and what we don’t want enough—is that all a national border is?

In the spaces surrounding disciplinary borders, like the borders of countries, we may find things that we might relinquish, or we may find things we want. In these permeable spaces, leaky spaces there are opportunities for culture, practice, and exchange. These borderscapes are lively, transgressive, and dynamic and might tell us that migration—all kinds of migration, across borders and disciplines—is not just important but completely essential.

Calais: 2016

To begin with, when first asked to go to “the Jungle” refugee camp in Calais as a volunteer, I was reluctant and looked for reasons not to go. The idea of going into the environment that I had seen so much of in the news made me feel really uneasy. The word “jungle” conjured all kinds of thoughts about lawless, wild places. Was this why I was unwilling to go? I asked myself. What was this fear? Was it racism? Was it my racism? It never feels good to use that word so close to oneself. I had never considered myself to be “one of them.”

I wondered where this apprehension, this fear, had come from. My only connection with the Jungle up until that point had been through what I’d seen in the papers and the television. The media predominantly showed negative or tragic depictions of the refugee situation to reveal the “truth,” to prod empathy. There was also the media feeding right-wing, “Brexity” positions, describing people as swarms as our prime minister, David Cameron, had done. They were also prodding and feeding something else, something much darker. Fear was being generated and exploited in the arguments about the UK borders. The rhetoric in some of the papers was nourishing nationalism.

Both sides of the media had played a role in “Othering” people through the images we saw of squalor, violence, crowds locked behind barbed wire, death. And going back to my own apprehensions about the place: Maybe I wanted to remain detached from a situation that was “too hard to see”? Perhaps I was scared of the situation, of the people? I decided (perhaps conveniently) that the media were to blame for my fear. This fear of the “Other” or the “media Other” felt important to discuss. To admit.

And there I was, eventually, in Calais, pondering my own flaws. I had been scared of this place and its multinational inhabitants, who were on the whole people from war zones in the Middle East and Africa. Consciously or unconsciously, I chose to displace my fear and put it at the hands of those who’d been representing these people. The media became my scapegoat for my own form of racism. The constant portrayal of the populations had put something negative in my head, and I was certain I wasn’t the only person it had happened to.

On the way to Calais, my colleagues and I were thinking that we’d just go as volunteers. To help. We were not going into the camp as a way to explore design or do practice. That would be wrong, this was serious. Too serious for our dabbling. The position of practice, of my practice in the context of the Jungle, was something that raised questions. Firstly, “practice,” beyond direct or pragmatic actions, seemed abstract or lacking the intent to tackle problems head on. I kept thinking of Cameron Sinclair and Architecture for Humanity, with its direct actions and outputs that had direct, tangible benefits. I’d gone to the camp to “help,” but there came a point where the help was doing almost nothing, patching up shelters that were soon to be demolished when the camp closed several months later. It was a dismal situation. Being “helpful” at times felt useless.

The collaborations and work in Calais and later, Lesbos, were intimately entangled reactions to media coverage of the migrant crisis. At the intersection of these experiences, I began to explore what a practice of “collaborative coverage/journalism” might produce and why it was important to try to address the current coverage of the human crisis.

The resulting little archives and films are ongoing. Far from perfect as things, they nevertheless raise some questions and present opportunities. They are done in a spirit of collaboration and attempt to present a different truth.

Maybe the story goes like this: even though the now-established critical design canon was wide eyed, unleashed from commercial roles, it was a little shaky around ideas of what it could achieve. But in fact, not knowing provided a hunger to produce, mess around, and simply see where this stuff could be in the world. I’m pretty sure at the beginning there was no coherent strategy. Maybe The Great Gonzo had a similar lack of life plan. Early strategy-lessness. Sometimes, vague, badly, or ill-directed pursuits throw up important opportunities for questioning—in this case, the strangeness of borders: how they are often meaningless but given meaning and codified through time, law, and definition; about how geopolitical designs fabricate borders between inside and outside, self and other, and yet freedom, joy, and play persist in spite or maybe even because of being on the other side of the West’s liberal “freedoms.”

Formalized by fences and checkpoints, entry is permitted with the “correct documents.” There were few correct documents in Calais, a space that had become a bottleneck for thousands of people without the right papers, without the right international descriptions.

Movement of Freedom

Movement of Freedom is a reaction to a piece of graffiti inside the heavily secured Moria refugee camp on Lesbos. “Movement of freedom” became an alternative or a replacement for the word “migration” or “migrant”: words synonymous with suffering for some or with something darker for the right-wing factions revealing themselves across Europe. This broadcast is simply an edited selection of movement collected by myself and others over a four-month period. Mohamad, my friend, collaborator, and a refugee from Iraq, would routinely send me clips from the camp. Initially this footage was extremely disturbing and violent. We decided to keep a focus on other portrayals from the island, where movement does not exclusively mean the trudge usually implied with migration. It did not mean just fleeing or escaping.

Swimming Not Sinking

Swimming Not Sinking presents an alternative to the all-too-familiar and tragic scenes of refugees in water. For years, the plight of people making dangerous crossings has been documented and presented with terrifying occurrence as people make their ways across the perilous stretches of water between Libya and Italy, Turkey, Greece, and elsewhere. The coasts of Greece are strewn with collapsed dinghies, and the death toll is tragic. Dinghies and the ever-present fluro-orange life jackets have become synonymous with death, not life.

Mohamad made six attempts to cross from Turkey, each costing around eight hundred euros. On his seventh attempt he was successful, arriving in Lesbos after a two-year journey from Iraq, where his family had been bombed in their home.[/commentable]

Working with refugees in Greece, I also met volunteers, many of them refugees themselves, who were organizing swimming lessons off the coast of Mytiline. For some, the lessons provided a way to deal with traumas they had suffered during their journeys. Often dinghies were slashed just off the coast by Turkish authorities in what was understood to be a perverse and dark deal with Europe. For others, the classes were simply about learning to swim and have fun.[/commentable]

Many of the people I was working with sent me footage. They made the crossings in overcrowded, flimsy boats. The images were familiar and dramatic, similar to what I’d seen on numerous occasions in the news. The footage was often taken to locate the refugees in international waters, which would define where they would be transferred if picked up by the coast guard (in these cases, Greece).[/commentable]

We agreed to film the swimming lessons; this led to this alternative view of “refugees in the water,” offering another version of people who don’t always drown and for whom tragedy is not a constant companion.[/commentable]

Bankshots and Spinball

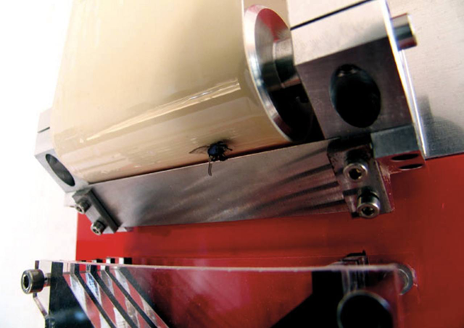

Bankshots and Spinball is from the first footage I made, somewhat cautiously, as I entered the center and NGO where refugees from the Moria camp came to visit to learn Greek and English. They could also do weight training and play basketball.

The camera was placed below the hoop, and I recorded the ball going through. There was interesting audio next to it: people cheering, and then a boom as the ball landed next to the camera. The hoops became targets that had a dark resonance with where people had come from, particularly those from Iraq and Syria.

These are great projectiles, and the hoop is a benign target.

Shadows across Europe

Shadows across Europe: this segment is made with a good friend, a political refugee from Mali whose identity and whereabouts had to be kept anonymous. Usually in the news, blurring, pixelating, and voice distortion cast a sinister layer over those they attempt to protect. We decided to explore a more playful representation and began to exchange shadows across WhatsApp. These clips, once edited, were passed to a poet from Iran who was staying in the Moria camp. He wrote a poem about the shadow clips, and this was then translated and read out by HDPDT, which is the alias of my anonymous friend.

Gum Blow

Gum Blow: these clips were very spontaneous and arose from talking with a friend from North Africa about a way to reveal a lighter side of people in the camps whilst exploring anonymity. Clips of gumballs inflating and popping were going to be edited together. Ayoub, Ayoub’s friend, and Lofti started to play with the gum and the camera, which resulted in a short clip of four men who then decided they didn’t want their faces hidden anyway.