Im/Explosión: A Conversation with Diseño Detonate

Armadillo

Mutante

Stacey Moran and Adam Nocek: We’re wondering if you could tell us a little bit about your work as designers. I (Adam) recall meeting you for the first time on a trip to Bogotá, and I was immediately taken by your work. At that time, you mentioned that you’re both designers who work with film. This really intrigues us. There is, of course, a whole tradition of design documentary—related to visual ethnography—but this doesn’t really seem to capture what you’re up to. Or maybe, your work is closer to ethnographic fiction in the medium of film, but you also conceive of these films as part of a design practice. Can you tell us a bit about how you conceive of your work with film as design?

Diseño Detonante: We acknowledge that we are not official filmmakers, and nor is it our intention to be, since we feel that creation and exploration do not require licenses. However, we felt like playing this game to challenge the conception of who has the “right” to make films, and likewise, who has the “right” to design. We live among worlds that are almost entirely designed, and this everydayness/reality that we are sold is only one possibility among many: just another fiction subject to be disobeyed, mostly due to its very nature of imposition. Thus, we decided to question “reality” in every possible way in our work, which has included film as an articulator and cultivator par excellence of both senses and techniques. Yet, we use film not because it works with sound and image as such but because other things without these classifications can result from such a union. This allows us to create worlds/realities with complex atmospheres, mixing techniques and exploring design at infinite layers, producing immersions, “entrailments,” and estrangements from many other places.

We share these two fictions as layers of depth that are crossed in and by what is thought of as reality. These two stories reflect our critique, most of which lies in the creative process itself, i.e., how a film is made, how it creates and breaks circuits, how and where it is exhibited, and what it enables. Therefore, it is a design practice in many temporalities, where production is a part of a more extensive design process. In this way, what is designed is not only the “inner content” of a film but the entire way of relating to it and lending it continuity through the weaving of experiences, of the dialogue that, in its course, designs us. Both in the narrative and practical dimensions, what we do is the outcome of questioning “reality” from within “reality” itself.

If experience results from navigating through the unknown—and that is a vital condition that enables movement-movements—then an extension of experience would be its empowerment beyond the individual bodily boundaries and the notion of the uniqueness of reality that derives from it.

In this sense, although film is not the only possible way, we recognize that it has a lot of potential. However, we feel that the task of designing experiential extensions and abysses of uncertainty is a responsibility that deserves and requires several dimensions of care. In our view, a design is composed of multiple designs that function within a common narrative. A story has multiple languages (which are also fictions), many of which are ephemeral and emerge from the story itself to function singularly within it; they then disintegrate to enable mutations-mutuations. This means that, for example, just as we design a script autonomously, we want to take on the other technical dimensions (illustration, animation, musical composition, photography, etc.) and their potential to alternate tensioning and dissonant layers, even if we are not specialists in these areas. The reason is that each story asks us how to be felt, seen, and heard. Another dimension of the same care is directed at ourselves: we feel that we do not want to stop discovering ourselves, but that to do so requires mobilizing ideas/bodies/techniques. Autonomy is fundamental in this process, especially when the contexts demand it and when what we do is not driven or mediated by any economic resource, besides being (on purpose) on the border between different disciplines and indisciplines.

Each short film has a particularity, an intimate and singular practice that is nourished by the territory and the community with whom it is made and, clearly, by our relationship and interaction with it. At no time do we feel like external agents; the film is precisely the outcome of our mutual resonances. The experience not only unfolds as a finished product but emerges from the very moment of its making. Perhaps “audiovisual ontological design” is an apt name for these experiential prostheses of one’s alternate lives. They are an immersion in another reality and an estrangement of the normalized and the designed—the imposition and placement in our environment that is not only based on objects, apparently empty of intentions, but also based on understandings and relationships.

For us, a film is more than a tool for information analysis or research—it is an extension of living experience, like prostheses that modify bodies, senses, and distances. In other words, an extension that requires a complex and singular design and dimensionality. Nor do we feel that a culture or a context can classify certain knowledge or ways of feeling, perceiving, or relating to life. On the contrary, we feel that other kinds of sensitivities are also required, since they make us leave behind the position of the analyst, researcher, or designer while placing ourselves in the very experience of the community, of the dialogue that lets us share the emotion or the fears that it generates. There, for a moment, we stop seeing others as subjects of analysis. This is because even the problems have dimensions that often overflow these kinds of limitations, and the unfolding of the experiences will tend to become something uncontrollable. And controlling it is not what we want. For this reason, ethnography, even if we think of it as a broad methodological category and very useful to characterize diverse problems in the territories, is not our field of action.

We propose a design for and from disobedience that detonates in us first. A film is a design based on a constellation of designs, a singular and expandable symbolic configuration, an open design that even reveals itself to us, questioning and disobeying us.

Stacey Moran and Adam Nocek: What strikes us about both films featured in this issue of Techniques Journal is the contrast between seriousness and playfulness. Mutante and Armadillo both tackle incredibly difficult topics, ranging from biophysical technologies of deception and control to the effects of coloniality, the realities of urbanization, and even the precarity of life itself. Yet, these challenges are matched with an equal measure of whimsy: in Mutante, for example, the worlds of fantasy and play are layered over (both thematically and visually) the harsh truths of urban life in this unnamed Peruvian community. Not only is the viewer asked to negotiate these two realities (displayed in the contrast between the setting and the action of the film), but they are abruptly reminded of how complex their relation is when shots of children playing with toy megaphones, “as if” they were weapons, cut to shots of protest, endless cycles of data extraction, and the colonial imposition of European languages. What looks like “child’s play” is utterly serious and cannot be disentangled from the political struggle of hearing the voices of the voiceless. Can you speak about how you trouble distinctions between fantasy and reality, or between seriousness and play, and why this is politically important to your practice?

Diseño Detonante: A game is a political (micropolitical) act with the potential to transform and engage other senses of life and community; for this reason, it is also a systematic target of discursive and commercial control. Games and toys are designs that situate, designs that shape logics and thoughts. Play has been instrumentalized with the appearance of innocence and incompleteness, or as if it were a set of small and disconnected simulacra. It has been infantilized and controlled (very controlled). This can only suggest that it is something dangerous, as risky as children themselves, as risky as fire or doubt. This means that for us, liberating games, at least from the little things we do, is as indispensable as the provocation of questions and events.

Delving into your interpretation, Mutante could be a game, fun but complex, in which life is involved in infinite ways and dimensions but where the game is in itself the purpose: to play is the discourse, the cause, and the consequence. However, while playing, relationships, voices, and times that are not part of a single type of narrative are accentuated and mobilized because they also involve other bodies, contexts, dystopias, desires, resistances, etc.

To play is also to make a short film, because it is to provoke an event, a crack, a color; to bring a virulent reality to the official reality. This is in itself an action that can trigger, if not transformations, at least questionings, sensations, and estrangements.

To raise doubts is in itself to begin disobeying, to find paths that can be even more deeply and more intimately felt than “reality.” It means that when walking through these contexts, when everyday life is experienced (hence our decision to fictionalize from there), the experience is different and draws on other references. This breaks the slim and apparently strong armor imposed by those who hold power (and who have held it for centuries, along with its institutions). This power has been not only imposed but normalized and almost entangled, mutilating our capacity to question, disobey, and transform it. This is essentially political, because it is to make us one by one agents of our lives, renouncing the individualized form of action and making it possible for us to act in collective ways, trespassing territories.

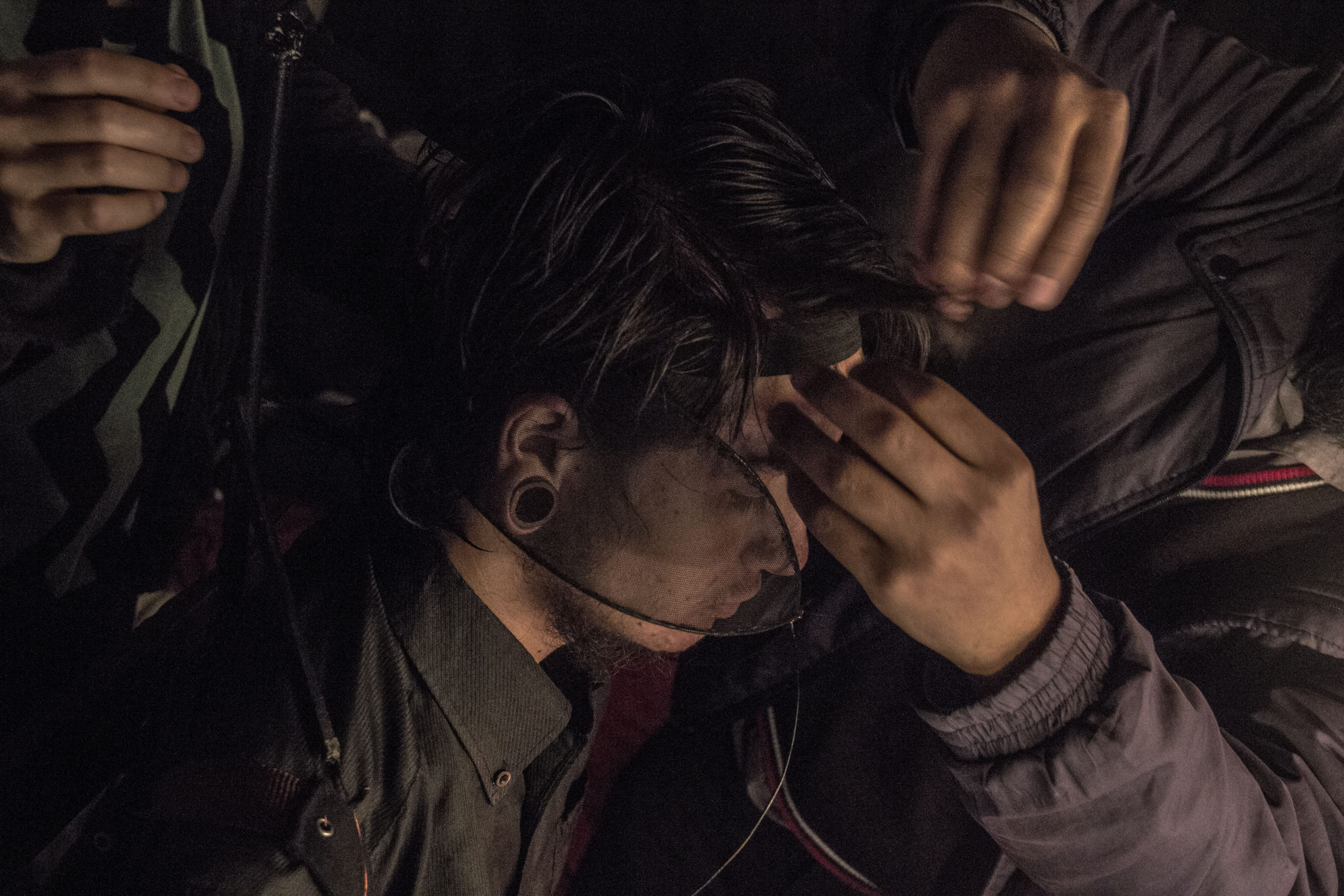

Stacey Moran and Adam Nocek: We think there’s a nightmarish quality to Armadillo. This isn’t simply because of the setting, the diegetic and nondiegetic sound, the editing, and so on (although they all contribute significantly to this feeling) but also because there doesn’t seem to be a clear way out of the piece. Once you’re in the “dream,” there’s no waking up. We say this because it’s hard to find a trustworthy external referent that doesn’t fold back in on itself and become a part of the dream/nightmare. For example, there’s the dominant narrative about the externalization of the human-armadillo brain (not unlike the lizard brain) and its responsibility for emotion and deception. Yet, this information is given to the viewer through the news media, which is itself a site of deceptive control. And then, as if to complete the circle, there’s a scene (starting at around 8:56) that seems to suggest that the “human-armadillo” is wired to pick up radio signals, which leaves us wondering whether the nightmare concerns the fact that deception and information are one and the same, and humans are responsible for this. This may in any case be us searching for our own referent in this incredibly complicated piece, but we’re wondering if you could speak about how news media and deception work together in Armadillo.

Diseño Detonante: These structures have been interpreted in many ways; in each exhibition is a constellation of views that are also very complex but diverse. The most powerful thing about producing open-source material around issues that can be complex is that we end up receiving the same degree of complexity for each interpretation. In this case, seeing the structures as antennas capturing radio signals opens up the narrative possibilities in a story that was written just for that. Thinking about it from that place, it becomes very revealing for us, because a hypermedia culture may moderate those structures in which, while information about the experience is produced, experiences are negated and information about the encounter nullifies the encounters.

We will delve into your interpretation (actualization) because we are not interested in talking about “what the fiction wanted to say” but about what it has produced and produces now. We will then try to put in dialogue our concerns by interweaving them with your interpretations to unfold the narrative.

There are two scenes alluded to in your question. In minute 2:52, after leaving what could probably be a dark room, bedroom, workshop, intimacy, mind, or whatever it may represent, the atmosphere changes, and more usual elements are found within what we would call “real life,” or everyday life with all its automations. This includes the sound of the radio, where a voice reveals an interesting similarity between the order Cingulata (origin of the armadillo) and the cingulate gyrus (in the human brain). However, the form of the information is striking: its schematic and encyclopedic nature contrasts with the intrusion of coffee spilling, breadcrumbs randomly falling on the table, and the sound of the bread and egg being crushed. It’s a juxtaposition of parasitic elements, percussions where the objects take on a special protagonism that expresses themselves and gives character to the events and even to the little expressiveness of the characters. Like contained chaos that subtly but desperately escapes. There is no way to capture or organize all the details of the experience, which results in overflowing any scientific definition; and, for the same reason, it is discarded by generic information systems, where everything is reduced to servile data to control that which can be consumed and quickly forgotten.

To go deeper into the second moment to which you refer (minute 8:56), we can think about the relation of corporealities with the armor-structures that you have interpreted as a media burden or objects of radial reception, which, to go a little further, could perhaps represent technology, understood more broadly. As an indispensable associated medium for the encounter, technology is in the formations and deformations we give it. It is, then, a way of transferring information that, in most cases, implies a unique way of receiving it and thus requires a forced adaptation to a mechanism that stylizes and modifies the postures-relationships. Therein lies the deception: in the implied disconnection, a treatment of informatic asepsis that on the one hand consists of cutting, classifying, packaging, and distributing according to a certain kind of interest and on the other hand consists of cutting (even more), consuming, believing, and accumulating data.

Throughout the short film, there seems to be a special relationship between these artifacts and those who carry them. Like a symbiosis in which there is no longer a difference between where the person “ends” and the artifact “begins,” and vice versa (this is something that is shared with Mutante). In many of the conversations we have had, we have been told that it seems impossible to get rid of these structures, because somehow people need them to exist. But even so, at this point in the story, there remains the feeling that these armors expand into the entrails, which makes them very dangerous. Moreover, there remains a doubt about how material the structures are, or whether, like information, they are immaterialities that silently shape, determine, and govern us.

Stacey Moran and Adam Nocek: Sight and sound seem to be very important senses in Mutante. There are voices, languages, and words that are heard and unheard; indeed, the mouths of children are covered, and they never speak directly to us (the viewer), but we’re asked to listen to them, nevertheless. Sight also seems crucial here, since Mutante opens and closes (literally through a swipe) with the eyes of children. Can you tell us more about the importance of sight and sound in the film, and in particular, what we’re not seeing and hearing?

Diseño Detonante: We are shaped mainly by what we do not see or hear. We are shaped, formed, and deformed by ideas. When we sit in certain ways and not others, or when we use certain things and not others, we are responding to the framework of ideas in which we move. What else are the artificialities in which we live, if not ideas? Our acceptance or denial of them, and the regimes of the paradigm of which they are part, determine us. Obedience or disobedience to ideas presupposes a design of the self—either imposed, in the case of obedience, or one as autonomous as possible, in the case of wanting to walk the uncertain paths of disobedience.

In Mutante, the visible and the sonorous are somehow deceptive and incoherent, and like Armadillo could be interpreted as a dream. However, in our case, we will never know which story is more nightmarish than the other, since both circumstances are somewhat extreme. If they had any pretension, it would be to question convictions, to question identity and the paradigms around them, to question the notion of control, permanence, and belonging of bodies as units.

All this relates precisely to what we do not see, to what we do not hear, and to what we apparently do not feel. Mutante explores other landscapes, other navigable bodies, but it is not about traveling from one place to another. Everything is happening simultaneously. We can be in many places, and we can represent many things simultaneously, even without realizing it; in the same way, we may not be anywhere at all. The whisperers (those elongated objects) are also terroristic and radical weapons, because they interrupt and create leaks towards other dimensions. The whispers (those profound voices) create transitions between the layers that we are, dissolving and deforming them until we cannot distinguish an “outside” or an “inside,” “the others” or “me,” “the territory” or “the body.” A whisper has the power to transform, to rearticulate life. However, in most cases, we only perceive it when the noisy rumblings accumulate. The whisper is also what remains in the form of silence.

We see one body inside another body and many others inside what looks like only one. Sometimes it might seem that all the children are the same character, composed by many others, in a permanent conflict and self-confrontation that translates into constant mutations. Yet, the screen flickers, as if those who observe were also a layer within the same story, a layer of the same character. But this remains only a spontaneous way of interpreting an open-code story, one of multiple and possible languages.

This question also allows us to describe how fiction works from our design work. Each fiction is like a ray of light that filters through some existing crack in convictions. Then, each beam of light is a fiction and a crack at the same time. A bombardment of fictions is a bunch of colored threads that invasively enter what we consider reality, towards all directions, with their singular shades that meet and expand the spectra of the imagination by creating moving holograms of what is possible, of what may be outside. However, something tells us our entrails also remain outside, in the infinite. Fictions also function as manifestos that reveal the cracks of discourses and words; we do not assume that this is comfortable either, and we also design to produce discomfort on purpose. Just as realities are the matter in which realities navigate and from which fictions are fed, fictions are the matter in which realities navigate and from which realities are fed. This sometimes makes “reality” seem to us a little more fictitious than fiction and fiction a little more realistic than “reality.”

Stacey Moran and Adam Nocek: Can you talk about the making of Mutante? What were the circumstances that brought you to Peru? How did you meet the stars of the film? And how did collaboration with members of the community work?

Diseño Detonante:

The circumstances:

We arrived in Peru by coincidence and consequence, due to a decided drift and a geographic and temporal opening. Before we become articulated to any process, there are always conversations and exchanges that allow us to find proximities or distances, which is essential for us. We ask ourselves, Why? What for? With whom? . . . and in most cases, these are processes that are willing to question even their own convictions, and it is with them that we work. Our decision lies in these choices, trying to distance ourselves as far as possible from the logics of consumption, productivity, and speed.

Thus, at first, we came to the Amazon with the idea of giving continuity to Lumbre en el viento, a “nondocumentary” series that connects autonomous territories resisting multiple manifestations of systematic dispossession. The first chapter was called “Lumbre en el viento—Istmo de Tehuantepec,” made in Mexico from 2017 to 2018. But as we said before, sometimes the projects disobey us—in this case, to the point that we found there were still many other roads to travel, other kinds of care, times, encounters, and connections from other corners of the Colombian Amazon. But we were already there, so close to Peru, that we let ourselves be carried away by the river and curiosity, without economic resources but with the conviction that we could play between logics and frontiers. Given that this has been about that all along, we know the game of “undermining the preestablished fictions” with our own fictions is very important. So, the border crossed us as we traveled the Amazon River, arriving in Peru. And after a couple of weeks, between walks, “informal work,” and exchanges, we managed to get to Lima, where a friend of a friend of a friend, someone completely unknown to us, gave us the best surprise of the trip.

Protagonists:

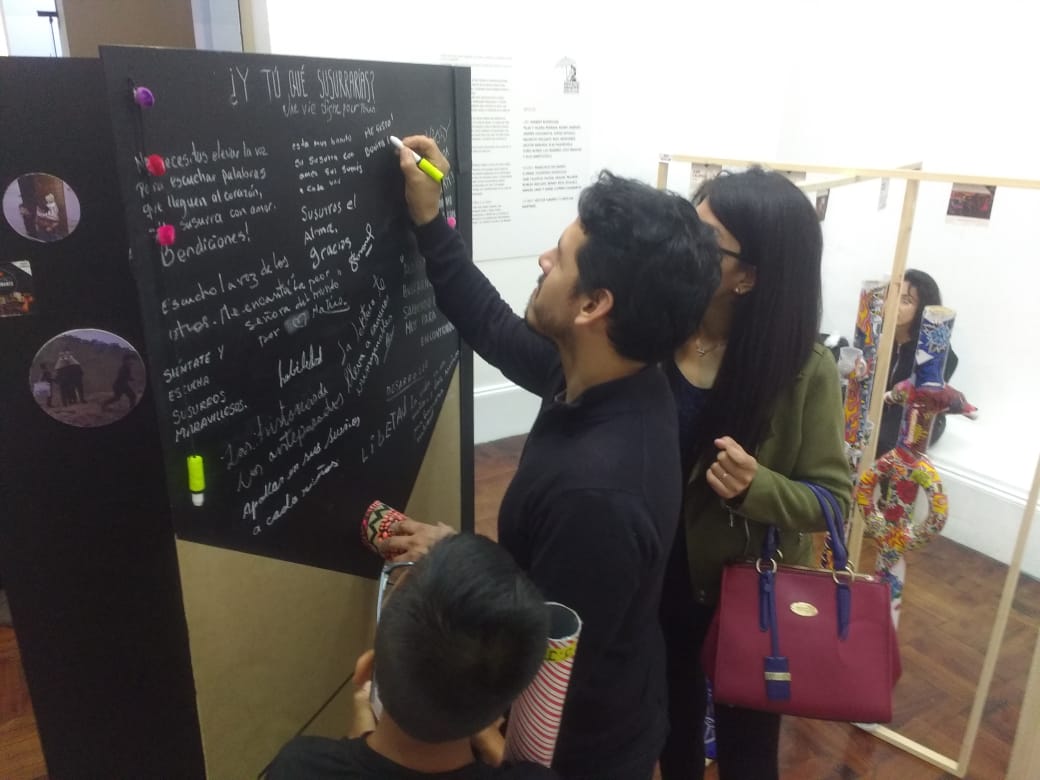

Lima Norte—Puente Piedra—Santa Rosa—Quijote Neighborhood. If you have never been to Lima or have never entrailed it, these names possibly do not say much and may only be taken as connections with an imaginary of roads and remoteness, one of the many gray Limas that coexist in their own disorder. Among mountains populated by migrant dreams, we found a little fire that burns and fills everything it touches with light and energy. It was a little neighborhood in a periphery, which like all other peripheries is the outcome of impoverishment and dispossession. However, it is a powerful generator of meaning of life and resistance, as is “Proyecto Quijote para la vida” (Quixote Project for Life), which arises from, for, and by the community. Children there are not passive receivers of information (as in standardized educational systems) but active creators of their own narratives. They not only learn to read books but also realities and contexts. Mutante is only a part of a more complex and articulated process that emerges when we meet the silent protagonists of the story, “the whisperers”: elongated tubes, painted and frequently used by children. These require special care, since the children must whisper, abandoning the idea of raising their voices and supposedly gaining respect by doing so; whoever is intercepted by them must in turn stop and listen carefully. Whisperers are activated in public spaces, where something similar to an ambush happens: where time stops, and a small communicative bond is created, a surprising, fleeting, but intense interaction with passersby. For this reason, to the disruptive and curious, the “terrorist” is included since it puts in check the daily life and the logic that rules it.

Mutante:

We began then to alter the meanings, with an unfolding of fictions that imply diverse contexts, relationships, forms, and languages that were connected by three acts. The first was a five-meter mural, which was our first connection with the neighborhood passersby and an introduction to the whisperer as a powerful and mysterious tool of care, which suggests listening, feeling, and thinking—a stop and a jump. From this mural, from the interactions it triggered, and from the context/territory itself, the second act emerged: the assembly of an exhibition in downtown Lima, which whispers other times, bringing the neighborhood to the museum, shaking its static airs, and transforming the typical “Don’t touch” into a “Stop, feel-think, whisper-listen!” It is an invitation to take agency, to do something. It was in these processes, in which we shared daily life, that we generated bonds of trust and recognition, mainly with the mothers and children. But as expected, the vitality of a process cannot be summarized on a wall or represented in a museum; instead, we have an excuse to create and take agency over dreams, community experiences, and autonomy; to contemplate how life cannot be territorialized, because it transcends spaces and creates border experiences between identities, bodies, and histories.

Mutante is our third act in this process: a repercussion of all this understanding, although located in multiple porous layers that also reveal other dissonant and fractured soils—different soils, just as present, but based on consumption, speed, and the hostility of which we are also part. Yet, paradoxically, we did not leave the everydayness to make this fiction. Mutante is one of many continuations of children’s relationships with constant surprise, motor curiosity, and the paths between the mountains, which are the same ones they travel daily, the same sky that influences the colors of their vibrant houses and stories. On the other hand, there is the magic of the immaterial everydayness, where affections, complicities, even territories are found. But there is also the layer of that which is not explicit, such as the constant subjection to other bodies that are not necessarily liberating. And the mutual and unstoppable mutation between lives that touch, collide, interact, and connect. A totally self-managed short film where, just as we recycled materials, we recycled the daily lives and imaginaries of natural actors and their own locations. In this project, as in Armadillo, we did not require economic resources, but we did require other times, exchanges, sharing, and links with people and their realities.

Stacey Moran and Adam Nocek: In a previous conversation, you both mentioned that these films are best experienced as a part of a “workshop,” as if to say they aren’t complete without conversation and further engagement. Can you talk about this a bit more? In other words, how might these pieces function less as experimental films meant to be viewed in a dark room on the film festival circuit and more like tools or techniques for generating new modes of intervention? Might this also help explain the way films are a part of your design practice?

Diseño Detonante: We are gradually generating twigs of a mangrove, of a rhizome, of something that is essentially connected. That is perhaps one of the things that interests us the most: to reveal to ourselves that everything is connected, that there is an implicit relationality in all forms of existence that allows us to be and that requires our care. It is urgent to associate “trivial” or “insignificant” everyday actions with more complex systems of thought in order to stop purposefully distancing and justifying ourselves to avoid taking responsibility for or feeling involved in the problems surrounding us.

We can think, for example, of a soda and its design for consumption and immediate disposal. To buy it is a legitimate and individual action, an exercise of free consumption apparently disconnected from any political issue. Still, on the other hand, this “small” action is full of repercussions that implicate violence at many levels. In any case, for those who consume, it is only a drink that they will hold for a few minutes, nothing more, because that is the idea disseminated through the media and advertising. Just like that soda and that advertising, most designs and films are conceived and consumed in that same logic: to satisfy the endless chain of market-power-ego, to educate for denial and rejection of complexity, to undermine care and encourage obedience, to take part in and induce a schizophrenic reality of destruction, and to defuturize in the name of “freedom” and the “good” life.

We are clusters of ever-closing and hyposensitive organs, fragmented and fragmenting, mandated by consumption, production, and spectacle, frantically jumping from experience to experience, from one design to another, even from one person and place to another. Insatiable, unsatisfied, without objections, questions, agency, or disobedience. Bringing this critique to the realm of design, we find ourselves with one design that remains servile and productive towards every system of oppression.

In the face of this, we activate our questionings and desire for disobedience, becoming in our doing, fictionalizing the rituals and the way of experiencing as if coming from other places, based on other connections. This feeling-knowing that everything is connected makes us want to subvert how relationships are founded; to subvert languages, spaces, and screens; to dismantle borders, inducing other times and careful conversations that are open to disagreement, to conflict, to “aimless” ideas, to bombardment and self-questioning and the detonation of words, which can result in bonds of recognition or collapses of convictions.

From this place emerges the workshop “Re-cognizing Ourselves in Difference,” a design embedded in the Colombian context (though it could be replicated in other parts of the world) as a disruptive response against the violence and fear that pierces us but does not determine us. This workshop constantly questions how we approach, know, and interact with others. In other words: it is a proposal seeking to reveal the logics that underlie the imaginaries and prejudices that determine our encounters and disagreements, our rejection of difference and fear and ultimately violence towards others, the territory we inhabit, and ourselves.

Armadillo emerges in principle as the workshop’s call for proposals. However, it is not a mirror of that workshop but another exploration, a different point of the rhizome that arises from the “previous” one. It is not the same, nor is it disconnected; it emerges from the same urgency of recognition and revelation. Both are a call to an autonomous, reflexive, and careful yet heartbreaking and uncomfortable creation of other narratives, of other life fictions that allow us other everydayness, presents, and life in the life. We believe the conscious but careful and loving destruction of what has been imposed on us, even if we have entrailed until we have incorporated it in ourselves, is a manifestation of care and urgent openness in these times of fear of difference, which even fears the difference that we are.

These are threads thrown into the air, free to be woven, and why not, entangled among many possibilities.

BIOGRAPHIES

Diseño Detonante

Diseño Detonante is a collective that was born in 2016. As a response to and taking agency with the context and everydayness in which they are immersed, they take design as a political practice of re-existence. They have worked both on their own and with different groups and/or individuals who work for a radical transformation of society and life. Thus, they have done audiovisual fictions as well as experiential workshops, documentaries, editorial design, photography, and interventions in transformative spaces.

Diseño Detonante is a collective that was born in 2016. As a response to and taking agency with the context and everydayness in which they are immersed, they take design as a political practice of re-existence. They have worked both on their own and with different groups and/or individuals who work for a radical transformation of society and life. Thus, they have done audiovisual fictions as well as experiential workshops, documentaries, editorial design, photography, and interventions in transformative spaces.

Designers for disobedience and for insubordination, creators of and in the collective Diseño Detonante: Hector Tabares Rodriguez (he/him/his), Audiovisual Producer + Carolina Martinez Tolosa (she/her/hers), Designer

Stacey Moran

Stacey Moran (she/her/hers) is Assistant Professor in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering and the Department of English at Arizona State University. Her work lies at the intersections of feminist theory and technoscience, design studies, and critical pedagogy. Her current research investigates how methods in the physical sciences provide a foothold for thinking about the materiality of knowledge production. Moran is also Associate Director of the Center for Philosophical Technologies (CPT), a global hub for critical and speculative research on philosophy, technology, and design. Through the CPT’s Global Education initiative, Moran directs a design summer school in the Netherlands and collaborates with the Laboratory for Expanded Design (LxD). Moran’s research informs her creative practice as a member of the design collective NON+, based in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Their work explores the relation among design, mythology, and material practices.

Stacey Moran (she/her/hers) is Assistant Professor in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering and the Department of English at Arizona State University. Her work lies at the intersections of feminist theory and technoscience, design studies, and critical pedagogy. Her current research investigates how methods in the physical sciences provide a foothold for thinking about the materiality of knowledge production. Moran is also Associate Director of the Center for Philosophical Technologies (CPT), a global hub for critical and speculative research on philosophy, technology, and design. Through the CPT’s Global Education initiative, Moran directs a design summer school in the Netherlands and collaborates with the Laboratory for Expanded Design (LxD). Moran’s research informs her creative practice as a member of the design collective NON+, based in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Their work explores the relation among design, mythology, and material practices.

Adam Nocek

Adam Nocek (he/him/his) is an Associate Professor in the Philosophy of Technology and Science and Technology Studies in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering at Arizona State University. He is also the Founding Director of ASU’s Center for Philosophical Technologies. Nocek has published widely on the philosophy of media and science; speculative philosophy (especially Whitehead); design philosophy, history, and practice; and critical and speculative theories of computational media. He recently published Molecular Capture: The Animation of Biology (Minnesota, 2021) and is working on his next monograph, Governmental Design: On Algorithmic Autonomy. Nocek is the co-editor (with Tony Fry) of Design in Crisis: New Worlds, Philosophies and Practices, The Lure of Whitehead (with Nicholas Gaskill), along with several other collections and special issues, including a special issue of Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities (with Cary Wolfe) titled, “Ontogenesis Beyond Complexity.” He is a visiting researcher at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis at the University of Amsterdam and previously held the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Visiting Professorship.

Adam Nocek (he/him/his) is an Associate Professor in the Philosophy of Technology and Science and Technology Studies in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering at Arizona State University. He is also the Founding Director of ASU’s Center for Philosophical Technologies. Nocek has published widely on the philosophy of media and science; speculative philosophy (especially Whitehead); design philosophy, history, and practice; and critical and speculative theories of computational media. He recently published Molecular Capture: The Animation of Biology (Minnesota, 2021) and is working on his next monograph, Governmental Design: On Algorithmic Autonomy. Nocek is the co-editor (with Tony Fry) of Design in Crisis: New Worlds, Philosophies and Practices, The Lure of Whitehead (with Nicholas Gaskill), along with several other collections and special issues, including a special issue of Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities (with Cary Wolfe) titled, “Ontogenesis Beyond Complexity.” He is a visiting researcher at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis at the University of Amsterdam and previously held the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Visiting Professorship.

Mario Orospe Hernández

Mario Orospe Hernández (he/him/his) is currently a PhD student in Religious Studies at the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, ASU. His dissertation research, entitled “Capitalism and Religion: On the Economic Life of the Smartphone across Secular Borders,” interrogates what have been the economic effects of secularization by developing a multi-sited ethnographic project in two key sites in the smartphone’s commodity chain: Silicon Valley and Uyuni, Bolivia. He previously obtained a master’s degree in philosophy and a BA in Political Science at UNAM, Mexico, focusing on the field of political philosophy, in particular in the traditions of Biopolitics and Liberation Theology.

Mario Orospe Hernández (he/him/his) is currently a PhD student in Religious Studies at the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, ASU. His dissertation research, entitled “Capitalism and Religion: On the Economic Life of the Smartphone across Secular Borders,” interrogates what have been the economic effects of secularization by developing a multi-sited ethnographic project in two key sites in the smartphone’s commodity chain: Silicon Valley and Uyuni, Bolivia. He previously obtained a master’s degree in philosophy and a BA in Political Science at UNAM, Mexico, focusing on the field of political philosophy, in particular in the traditions of Biopolitics and Liberation Theology.

Versión en español

Stacey Moran y Adam Nocek: Nos preguntamos si pueden hablarnos un poco de su trabajo como diseñadores. Yo (Adam) recuerdo que les conocí por primera vez en un viaje a Bogotá y quedé inmediatamente enganchado a su trabajo. En aquel momento, mencionaron que ambos son diseñadores que trabajan con cine. Esto nos intriga mucho. Existe, por supuesto, toda una tradición de documentales de diseño relacionados con la etnografía visual, pero esto no parece captar realmente lo que hacen. O tal vez, su trabajo se acerca más a la ficción etnográfica en el medio cinematográfico, pero también conciben estas películas como parte de una práctica de diseño. ¿Pueden contarnos un poco cómo conciben su trabajo con el cine como diseño?

Diseño Detonante: Partimos de que no somos cineastas oficiales y tampoco es nuestra intención, pero sentimos que la creación y la exploración no requiere de licencias. Este es un juego que nos nace jugar, retando la concepción de quiénes tienen “derecho” a hacer cine, y de igual manera, de quienes tienen derecho a diseñar. Vivimos entre mundos casi enteramente diseñados, y esta cotidianidad/realidad que nos venden, es solo una posibilidad entre tantas, una ficción más, sujeta a ser desobedecida y más aun, por su mismo carácter de imposición. Así decidimos desde nuestro hacer, cuestionar “la realidad” de todas las maneras que nos sean posibles, siendo el cine un articulador y cultivador por excelencia tanto de sentidos como de técnicas, no porque trabaje con el sonido y la imagen como tal, sino porque de esta juntanza resultan otras cosas sin estas clasificaciones. Esto nos permite crear mundos/realidades con atmósferas complejas, mezclando técnicas y explorando el diseño a infinitas capas, produciendo inmersiones, “entrañamientos” y extrañamientos desde muchos otros lugares.

Compartimos estas dos ficciones que son capas de profundidad atravesadas en y por lo que se piensa como realidad. Son dos historias en las que se refleja nuestra crítica, de la que gran parte está en el proceso en sí, en el cómo se hace una película, cómo crea y rompe circuitos, cómo y en dónde se publica y qué posibilita. Entonces, se trata de un ejercicio de diseño en muchos tiempos, siendo la producción una parte de un diseño más grande, lo que se diseña no es solo el “contenido interno” de una película, sino toda la forma de relacionarse con ella y darle continuidad a través del tejido de experiencias, del diálogo que en su curso, nos diseña. Tanto en la dimensión narrativa como en la práctica, lo que hacemos se deriva de la necesidad de cuestionar “la realidad” desde “la realidad” misma.

Si la experiencia se da al transitar por lo desconocido, y esta es una condición vital que posibilita movimiento-movimientos, entonces, una extensión de la experiencia es su potenciación más allá de las fronteras del cuerpo individual y de la noción de unicidad de la realidad dentro del mismo.

En este sentido, aunque no es la única manera, reconocemos que el cine tiene mucho potencial. Sin embargo, sentimos que la tarea de diseñar extensiones experienciales y abismos de incertidumbre, es una responsabilidad que merece y requiere varias dimensiones de cuidado. Desde nuestro punto de vista, un diseño se compone de múltiples diseños, diseños que funcionan todos dentro de una narrativa común. Una historia cuenta con múltiples lenguajes (que también son ficciones), y muchos de estos, son lenguajes efímeros que surgen desde la misma historia, para funcionar singularmente dentro de ella, luego se desintegran para posibilitar mutaciones-mutuaciones; esto hace que, por ejemplo, así como diseñamos un guión de manera autónoma, queramos asumir las otras dimensiones de la técnica (ilustración, animación, composición musical, fotografía, etc.), y su potencial para alternar capas tensionantes y disonantes aunque no seamos especialistas en estas áreas. La razón, es que cada historia nos pide el cómo ser sentida, vista y escuchada. Otra dimensión del mismo cuidado, va dirigida a nosotrxs mismxs; sentimos que no queremos dejar de descubrirnos, pero que para hacerlo hay que movilizar las ideas/cuerpos/técnicas, y en este proceso es fundamental la autonomía, sobre todo cuando los contextos nos lo exigen, cuando lo que hacemos no está impulsado o mediado por ningún recurso económico, además de estar (a propósito) en la frontera entre diferentes disciplinas e indisciplinas.

Cada cortometraje, tiene una particularidad, una práctica entrañada y singular que se nutre del territorio y de la comunidad con quien se hace y claramente de nuestra relación e interacción con esta, porque en ningún momento nos sentimos agentes externos, y justamente el filme resulta de nuestras mutuas resonancias. La experiencia no solo va hacia afuera como producto terminado, sino surge desde el momento mismo del hacer, tal vez le podríamos llamar un «diseño ontológico audiovisual» a estas prótesis experienciales de vidas alternas de unx mismx, a la inmersión en una realidad otra, en un extrañamiento de lo normalizado y lo diseñado; lo impuesto y puesto en nuestro entorno que no solo se basa en objetos aparentemente vacíos de intenciones, sino que también son entendimientos y relaciones.

Para nosotrxs, una película, es más que una herramienta de análisis de información o de investigación, es una extensión de la experiencia viva, como prótesis que modifican cuerpos, sentidos y distancias. Una extensión que requiere de un diseño y una dimensionalidad compleja y singular. Tampoco sentimos que determinados saberes o maneras de sentir, percibir o relacionarse con la vida, sean clasificables mediante una cultura o un contexto. Sentimos que también se requiere de otro tipo sensibilidades que nos hagan soltar la posición de quien analiza, quien investiga o quien diseña y nos situemos en la experiencia misma de la colectividad, del diálogo y compartamos la emoción o los miedos que nos genere, en donde por un momento dejemos de ver a lxs otrxs como sujetos de análisis, porque incluso las problemáticas tienen dimensiones que muchas veces desbordan este tipo de limitaciones, y el despliegue de las experiencias tenderá a volverse algo incontrolable, y controlarlo no es lo que queremos. Por esta razón la etnografía, aun pensándola como una categoría metodológica amplia, y muy útil para caracterizar diversas problemáticas en los territorios, no es nuestro campo de acción.

Planteamos un diseño para y desde la desobediencia, que se detone en nosotrxs primero. Un filme es un diseño basado en una constelación de diseños, una configuración simbólica singular y expandible, un diseño abierto que incluso también se revela hacia nosotrxs y nos cuestiona, nos desobedece.

Stacey Moran y Adam Nocek: Lo que nos llama la atención de las dos películas que aparecen en este número de Techniques Journal, es el contraste entre la seriedad y el juego. Tanto Mutante como Armadillo abordan temas increíblemente difíciles, desde las tecnologías biofísicas de engaño y control hasta los efectos de la colonialidad, las realidades de la urbanización e incluso la precariedad de la vida misma. Sin embargo, estos retos van acompañados de una medida igual de caprichosa: en Mutante, por ejemplo, los mundos de la fantasía y el juego se superponen (tanto temática como visualmente) a las duras verdades de la vida urbana en esta comunidad peruana sin nombre. No sólo se pide al espectador que negocie estas dos realidades (que se muestran en el contraste entre el escenario y la acción de la película), sino que se le recuerda abruptamente lo compleja que es su relación cuando las tomas de niños jugando con megáfonos de juguete, “como si” fueran armas, se cortan con tomas de protestas, ciclos interminables de extracción de datos y la imposición colonial de las lenguas europeas. Lo que parece un “juego de niños” es totalmente serio y no puede desvincularse de la lucha política por escuchar las voces de los sin voz. ¿Pueden hablar de cómo problematizan las distinciones entre fantasía y realidad, o entre seriedad y juego, y por qué esto es políticamente importante para su práctica?

Diseño Detonante: El juego es un acto político (micropolítico) con potencial para transformar e involucrar otros sentidos de vida y comunidad; por esta razón, también es un objetivo sistemático de control discursivo y comercial. Los juegos y los juguetes son diseños que sitúan, diseños que modelan lógicas y pensamientos. El juego ha sido instrumentalizado con la apariencia de ser algo inocente, parcial, o de ser pequeños simulacros desconectados entre sí. Ha sido infantilizado y controlado (muy controlado), esto solo puede sugerir que se trata algo peligroso, tan peligroso como lxs mismxs niñxs, el fuego y la duda. Esto hace que para nosotrxs liberar el juego por lo menos desde las pequeñas cosas que hacemos, sea algo tan indispensable como la provocación de cuestionamientos y acontecimientos.

Ahondando en la interpretación que han hecho (Stacey y Adam), Mutante podría ser un juego, divertido pero complejo, en el que se implica la vida de infinitas maneras y dimensiones, pero en donde el juego es en sí mismo la finalidad, jugar es el discurso, la causa y la consecuencia. Sin embargo, mientras se juega, se acentúan y se movilizan las relaciones, las voces y los tiempos que no hacen parte de un solo tipo de narrativas, porque también involucran otros cuerpos, contextos, distopías, deseos, resistencias, etc.

Jugar, también es hacer un cortometraje, porque es provocar un acontecimiento, una grieta, un color; traer una realidad virulenta a la realidad oficial. Esto es en sí una acción que puede desencadenar si no transformaciones, por lo menos cuestionamientos, sensaciones y extrañamientos.

Poner en duda, es en sí empezar a desobedecer, encontrar trochas que pueden ser incluso más sentidas y cercanas que “la realidad”. Hace que cuando se esté caminando por esos contextos, cuando se esté experimentando la cotidianidad (por eso nuestra decisión de ficcionar desde ahí), la experiencia sea otra, se recurra a otras referencias. Esto rompe la armadura estrecha y aparentemente fuerte de lo posible, armadura que ha sido impuesta por quienes detentan y han detentado el poder por siglos junto con sus instituciones, y que ha sido no sólo impuesta sino normalizada y casi entrañada, mutilándonos la capacidad de cuestionarla, desobedecerla y transformarla. Esto es esencialmente político, porque es hacernos de a pocos agentes de nuestras vidas, abandonando la forma individualizada de la acción y posibilitandonos hacer en colectivo, traspasando territorios.

Stacey Moran y Adam Nocek: Creemos que Armadillo tiene un carácter de pesadilla. Esto no se debe simplemente a la ambientación, el sonido diegético y no diegético, el montaje, etc. (aunque todos ellos contribuyen significativamente a esta sensación), sino también a que no parece haber una salida clara de la pieza. Una vez que se está en el “sueño”, no se puede despertar. Decimos esto porque es difícil encontrar un referente externo fiable que no se repliegue sobre sí mismo y se convierta en parte del sueño/pesadilla. Por ejemplo, hay una narrativa dominante sobre la externalización del cerebro humano-armadillo (no muy diferente del cerebro de lagarto) y su responsabilidad en la emoción y el engaño. Sin embargo, esta información se ofrece al espectador a través de los medios de comunicación, que son en sí mismos un lugar de control engañoso. Y luego, como para completar el círculo, hay una escena (que comienza alrededor del minuto 8:56) que parece sugerir que el “armadillo-humano” está conectado para captar señales de radio, lo que nos hace preguntarnos si la pesadilla tiene que ver con el hecho de que el engaño y la información son una misma cosa, y los humanos son responsables de ello. En cualquier caso, puede que seamos nosotros los que buscamos nuestro propio referente en esta obra increíblemente complicada, pero nos preguntamos si pueden hablar sobre cómo los medios de comunicación y el engaño funcionan juntos en Armadillo.

Diseño Detonante: Las estructuras se han interpretado de muchas maneras, en cada muestra se constelan miradas que son también muy complejas pero diversas, lo más poderoso de producir un material de código abierto alrededor de temas que pueden ser complejos, es que resultamos recibiendo el mismo grado de complejidad por cada interpretación, y en este caso, ver las estructuras como antenas captadoras de señales radiales, lo que hace es abrir las posibilidades narrativas en una historia que se escribió justamente para eso. Pensándolo desde ese lugar, se vuelve muy revelador para nosotrxs, porque esos entramados de estructuras pueden estar siendo moderados por una cultura hipermediática, en la que mientras se produce información sobre la experiencia se anulan las experiencias, y la información sobre el encuentro, anula los encuentros.

Ahondaremos en su interpretación (actualización) porque no nos interesa hablar de “lo que la ficción quiso decir” sino de lo que ha producido y produce ahora, entonces intentaremos poner en diálogo nuestras preocupaciones entretejiéndolas con sus interpretaciones y desplegando la narrativa.

Hay dos escenas a las que se hacen alusión en su pregunta: En el minuto 2:52, después de salir de lo que podría ser una especie de cuarto oscuro, dormitorio, taller, intimidad, mente o lo que sea que pueda representar; la atmósfera cambia y se encuentran elementos más habituales, dentro de lo que llamaríamos “la vida real” o la cotidianidad con todas sus automatizaciones, en las que se incluye el sonido de la radio, en donde una voz revela una familiaridad interesante entre el orden cingulata (origen del armadillo) y el giro cingulado (en el cerebro humano); sin embargo, llama la atención la forma de la información, su manera esquemática y enciclopédica de ser, que resulta contrastando con la intromisión del café que se derrama, las migas de pan que caen aleatoriamente sobre la mesa o el sonido del pan y el huevo siendo aplastados. Una yuxtaposición de elementos parásitos, percusiones en donde los objetos toman un protagonismo especial, se expresan y dan carácter a los acontecimientos e incluso a la poca expresividad del personaje. Como caos contenido que se fuga sutil pero desesperadamente. No hay manera de capturar ni de organizar todos los detalles de la experiencia, que resultan desbordándose de cualquier definición científica; y por la misma razón, son descartados por los sistemas genéricos de información en donde se reduce todo a un dato servil al control que pueda consumirse y olvidarse velozmente.

Para profundizar en el segundo momento al que hacen referencia (minuto 8:56) podemos pensar en la relación de las corporalidades con las armaduras-estructuras que ustedes han interpretado como una carga mediática u objetos de captación radial, que, para ir un poco más allá, podría tal vez representar la tecnología de manera más amplia; la tecnología como medio asociado indispensable para el encuentro, en donde el problema está en las formaciones y deformaciones que le damos. Se trata entonces, de una forma de transferir información que en la mayoría de los casos, implica una forma única de recibirla, por lo que requiere de una adaptación forzada a un mecanismo que estiliza y modifica las posturas-relaciones. Ahí radica el engaño, en la desconexión que esto supone, un tratamiento de asepsia informática, que por un lado consiste en recortar, clasificar, empaquetar y distribuir según determinada clase de intereses; por otro lado, consiste en recortar (más) consumir, creer y acumular datos.

En el transcurso del corto, parece haber una relación especial entre estos artefactos y quienes los portan. Como una simbiosis en la que ya no se diferencia el punto donde “termina” la persona y “empieza” el artefacto y viceversa (esto es algo que se comparte con Mutante). En muchas de las conversaciones que hemos tenido, nos han dicho, que parece que no es posible librarse de estas estructuras porque de alguna manera las personas las necesitan para existir. Pero aún así, en este punto de la historia queda la sensación de que estas armaduras se expanden hacia las entrañas, lo que las hace muy peligrosas. Además, ha quedado la duda en el aire de qué tan materiales son las estructuras o si como la información son inmaterialidades que veladamente nos moldean, determinan y gobiernan.

Stacey Moran y Adam Nocek: La vista y el sonido parecen ser sentidos muy importantes en Mutante. Hay voces, lenguajes y palabras que se oyen y no se escuchan; de hecho, las bocas de los niños están tapadas y nunca nos hablan directamente (al espectador), pero se nos pide que los escuchemos de todas formas. La vista también parece crucial en este caso, ya que Mutante se abre y se cierra (literalmente mediante un golpe) con los ojos de los niños. ¿Pueden hablarnos de la importancia de la vista y el sonido en la película, y en particular de lo que no vemos ni oímos?

Diseño Detonante:Estamos conformados principalmente por lo que no vemos ni oímos. Nos conforman, forman y deforman las ideas. Cuando nos sentamos de ciertas maneras y no de otras, o al usar ciertas cosas y no otras, estamos respondiendo al marco de ideas en que nos movemos, ¿qué más son las artificialidades en las que vivimos, si no ideas? nuestra aceptación o negación hacia ellas, y los regímenes del paradigma del que son parte, nos determinan, la obediencia o desobediencia a las ideas presupone un diseño de sí, ya sea impuesto en el caso de la obediencia o uno en la medida de lo posible autónomo en el caso de querer caminar las trochas inciertas de la desobediencia.

En Mutante, lo visible, lo sonoro de alguna manera es engañoso e incoherente, y al igual que el Armadillo podría ser interpretado como un sueño, aunque en nuestro caso, nunca sabremos cuál historia es más pesadillesca que la otra, ya que las circunstancias de ambas son algo extremas y si tuvieran alguna pretensión, sería la de poner en duda los convencimientos, cuestionar la identidad y los paradigmas que hay a su alrededor, poner en duda la noción de control, permanencia y pertenencia de los cuerpos como unidades.

Todo esto se relaciona justamente con lo que no vemos, no oímos y aparentemente, con lo que no sentimos, Mutante explora otros paisajes, otros cuerpos navegables pero no se trata de viajes de un lugar a otro, todo está pasando en simultáneo, se puede estar en muchos lugares y se puede representar muchas cosas al mismo tiempo, incluso sin darnos cuenta; de la misma manera, podemos no estar en ningún lugar por completo. Los susurradores (esos objetos alargados) son también armas terroristas y radicales, porque interrumpen y crean fugas hacia otras dimensiones; los susurros (esas voces en lo profundo) crean tránsitos entre las capas que somos, disolviéndolas y deformándolas hasta no distinguir un “afuera” o un “adentro”, “lxs otrxs” o “yo”, “el territorio” o “el cuerpo”. Un susurro tiene la potencia de transformar, de re-articular la vida, sin embargo, en la mayoría de los casos, solo lo percibimos cuando se acumulan los estruendos que ensordecen, y el susurro también es lo que queda en forma de silencio.

Vemos un cuerpo dentro de otro y muchos dentro de lo que parece uno, a veces podría parecer que todxs lxs niñxs son el mismo personaje, compuesto por muchos otrxs, en un permanente conflicto y auto confrontación que se traduce en mutaciones constantes, pero luego la pantalla parpadea, como si quienes observamos, también fuéramos una capa dentro de la misma historia, una capa del mismo personaje, pero esta sigue siendo solo una forma espontánea de interpretar una historia de código abierto, de lenguajes múltiples y posibles.

Esta pregunta también sirve para describir cómo funciona la ficción desde nuestro hacer diseño, cada ficción es como un rayo de luz que se filtra por alguna grieta ya existente en los convencimientos, entonces, cada rayo de luz es una ficción y una grieta al mismo tiempo; un bombardeo de ficciones es un montón de hilos de colores que entran invasivamente a lo que consideramos la realidad, hacia todas las direcciones, con sus matices singulares que se encuentran y amplían los espectros de la imaginación, al crear hologramas en movimiento de lo posible, de lo que puede estar afuera y algo nos dice que afuera están también nuestras entrañas, en lo infinito. Las ficciones también funcionan como manifiestos que revelan las grietas de los discursos y de las palabras; tampoco suponemos que esto sea algo cómodo y a propósito también diseñamos para la incomodidad. Así como las realidades son la materia en la que navegan y de donde se alimentan las ficciones, las ficciones son la materia en la que navegan de donde se alimentan las realidades, esto hace que a veces nos parezca “la realidad” un poco más ficticia que la ficción y la ficción un poco más realista que “la realidad”.

Stacey Moran y Adam Nocek: ¿Pueden hablarnos de la realización de Mutante? ¿Cuáles fueron las circunstancias que les llevaron a Perú? ¿Cómo conocieron a los protagonistas de la película? ¿Y cómo funcionó la colaboración con los miembros de la comunidad?

Diseño Detonante:

Las circunstancias:

A Perú llegamos por coincidencia y consecuencia, llegamos por una deriva decidida y una apertura geográfica y temporal. Antes de articularnos a cualquier proceso, siempre hay conversaciones e intercambios que nos permiten encontrar cercanías o distancias, y esto para nosotrxs es indispensable. Nos preguntamos ¿por qué?, ¿para qué?, ¿con quién?… y en la mayoría de ocasiones, se trata de procesos dispuestos a cuestionar incluso sus propios convencimientos, con ellxs es con quienes trabajamos. Nuestra decisión radica en esas escogencias, tratando de alejarnos en lo posible de las lógicas de consumo, productividad y velocidad.

Así en un primer momento llegamos al Amazonas con la idea de dar continuidad a “Lumbre en el viento”, una serie “no documental” que conecta territorios autónomos que resisten a múltiples manifestaciones del despojo sistemático. El primer capítulo se llamó “Lumbre en el viento -Istmo de Tehuantepec” realizado en México entre los años 2017 a 2018. Pero como decíamos anteriormente, los mismos proyectos nos desobedecen y encontramos que aún faltaban muchos otros caminos por recorrer, otro tipo de cuidados, tiempos, encuentros y conexiones desde otros extremos del Amazonas colombiano. Pero ya estábamos allí, tan cerca a Perú, que nos dejamos llevar por el río y la curiosidad, aun sin tener recursos económicos, pero con la convicción de que podríamos jugar entre lógicas y fronteras; pues de eso se ha tratado todo el tiempo, sabemos que es un juego muy importante, el juego de “minar las ficciones preestablecidas” con nuestras propias ficciones. Así nos cruzó la frontera mientras recorrimos el río Amazonas, llegando a Perú y después de un par de semanas, entre caminatas, “trabajo informal” e intercambios, logramos llegar a Lima a donde el amigo del amigo de un amigo; alguien completamente desconocido que nos dio la mejor sorpresa que tuvimos en el viaje.

Protagonistas:

Lima Norte – Puente Piedra – Santa Rosa – Barrio Quijote. Si nunca se ha estado en Lima, o si nunca se ha entrañado, posiblemente estos nombres no digan mucho y solo sean conexiones con imaginarios de carreteras y lejanías, de las tantas Limas grises que conviven en su propio desorden. Encontramos, entre montañas pobladas de sueños migrantes, un fueguito que arde y va llenando de luz y energía a todo lo que toca. Un pequeño barrio en una periferia, que como todas las periferias resulta del empobrecimiento y el despojo, pero es potente generadora de sentidos de vida y resistencias, como es el caso de Proyecto Quijote para la Vida, que surge desde, para y por la comunidad. Allí lxs niñxs no son receptores pasivos de información (como en los sistemas educativos normalizados), sino creadores activos de sus propias narrativas. No solo se aprende a leer libros, sino realidades y contextos. Mutante, es solo una parte de un proceso más complejo y articulado, que surge al encontrarnos con los protagonistas silenciosos de la historia, “los susurradores”: Tubos alargados, pintados y usados frecuentemente por lxs niñxs, que requieren para su uso, un cuidado especial, ya que se debe susurrar abandonando esa idea de alzar la voz, supuestamente ganando respeto al hacerlo; quien es interceptado por ellxs debe a su vez parar y escuchar cuidadosamente. Los susurradores se activan en espacios públicos, en donde sucede algo similar a una emboscada, y en donde el tiempo se para y se crea un pequeño lazo comunicativo, una interacción sorpresiva, fugaz, pero intensa con lxs transeúntes. Por esta razón, a lo disruptivo y curioso, se le incluye lo “terrorista” ya que pone en jaque las cotidianidades y las lógicas que las rigen.

Mutante.

Empezamos entonces, a alterar los significados, con un despliegue de ficciones que implican contextos, relaciones, formas y lenguajes diversos, que se fueron conectando mediante tres actos: El primero, fue un mural de cinco metros, nuestro primer vínculo con lxs transeúntes del barrio, y una introducción al susurrador como una potente y misteriosa herramienta de cuidado, que propone escuchar, sentir y pensar; un alto y un salto. De este mural, de las interacciones que detonó y del contexto/territorio en sí, surgió el segundo acto: El montaje de una exposición en el centro de Lima, que susurra otros tiempos, llevando el barrio al museo y sacudiendo sus aires estáticos y el típico “no toque” transformándolo en un “Deténgase, sienta-piense, susurre-escuche!”, invitación a la agencia, al hacer.

Fue en estos procesos, en los que compartimos cotidianidad, generamos lazos de confianza y reconocimiento, principalmente con las madres y lxs niñxs. Pero como es de esperar, la vitalidad de un proceso no puede ser resumida en un muro o representada en un museo; estos son más bien, una excusa para gestar y agenciar los sueños, las experiencias de comunidad y autonomía. Para justamente contemplar, cómo la vida no se puede territorializar, porque trasciende los espacios y crea experiencias fronterizas entre identidades, cuerpos e historias.

Mutante es nuestro tercer acto en este proceso: Una repercusión de todo este entendimiento, aunque situado en múltiples capas porosas que revelan también otros suelos disonantes y fracturados; otros suelos igual de presentes, pero basados en el consumo, la rapidez y la hostilidad de la que también hacemos parte. Paradójicamente, para hacer esta ficción no nos salimos de la cotidianidad. Mutante es una, entre muchas continuaciones de las relaciones de lxs niñxs con la sorpresa constante, la curiosidad motora y con los caminos entre las montañas, que son los mismos que recorren diariamente, el mismo cielo que influencia los colores de sus casas coloridas y sus historias; por otro lado está la magia de la cotidianidad inmaterial, en donde se encuentran los afectos, las complicidades, incluso con los territorios. Pero además está la capa de lo que no es explícito, como la sujeción constante a otros cuerpos que no necesariamente son liberadores. Y la mutación mutua e imparable entre las vidas que se tocan, chocan, interactúan y conectan.

Un cortometraje totalmente autogestivo en donde, así como reciclamos materiales, reciclamos las cotidianidades e imaginarios de actores naturales y sus propias locaciones. En este proyecto, como en el Armadillo, no requerimos de recursos económicos, pero sí de tiempos otros, de intercambios, compartires y vínculos con las personas y sus realidades.

Stacey Moran y Adam Nocek: En una conversación anterior, ambos mencionaron que estas películas se experimentan mejor como parte de un “taller”, como si dijeran que no están completas sin una conversación y un mayor compromiso. ¿Pueden hablar un poco más de esto? En otras palabras, ¿cómo podrían estas piezas funcionar menos como películas experimentales destinadas a ser vistas en una sala oscura en el circuito de festivales de cine, y más como herramientas o técnicas para generar nuevos modos de intervención? ¿Podría esto ayudar a explicar el modo en que las películas forman parte de su práctica de diseño?

Diseño Detonante: Vamos poco a poco generando ramitas de un manglar, de un rizoma, de un algo que está esencialmente conectado, esa es quizá, una de las cosas que más nos interesa: revelar-nos que todo está conectado, que hay una relacionalidad implícita en todas las formas de existencia, que nos permite ser y que requiere de nuestro cuidado. Es urgente asociar las acciones cotidianas “triviales o insignificantes” con sistemas de pensamiento más complejos; dejar de distanciarnos a propósito y de justificarnos para no hacernos responsables ni sentirnos involucradxs en los problemas que nos rodean.

Podemos pensar, por ejemplo, en una gaseosa y su diseño para ser consumida y desechada inmediatamente; comprarla, es una acción legítima e individual, un ejercicio de libre consumo, aparentemente desconectado de cualquier asunto político, pero por otro lado, esta “pequeña” acción está llena de repercusiones que involucran violencias a muchos niveles. En todo caso, para quien consume, solo es una bebida que sostendrá por algunos minutos en sus manos y nada más, porque es la idea que se propagó a través de los medios y la publicidad; así como esa gaseosa y esa publicidad, la mayoría de diseños y películas son concebidas y consumidas en esa lógica; satisfacer la cadena interminable de mercado, poder, ego; educar para la negación, el rechazo a la complejidad; minar el cuidado y fomentar la obediencia; hacer parte e inducir a una realidad esquizofrénica de destrucción y defuturo en nombre de “libertad” y vida “buena”.

Somos cúmulos de órganos cada vez más cerrados e hiposensibles, fragmentados y fragmentadores, mandatados por el consumo, producción y espectáculo, saltando frenéticamente de experiencia en experiencia, de un diseño a otro, incluso de una persona y lugar a otro, insaciables, insatisfechos, siendo sin objeción, sin preguntas, sin agencia, ni desobediencia. Trayendo esto al diseño, nos encontramos con uno servil y productivo frente a todo sistema de opresión.

De cara a esto agenciamos nuestros cuestionamientos y gana de desobediencia, siendo en nuestro hacer, ficcionando los rituales y la forma de experienciar, desde otros lugares, a partir de otras conexiones. Este sentir-saber que todo está conectado nos hace querer subvertir la forma de fundar las relaciones, los lenguajes, los espacios y las pantallas, desmontar fronteras provocando otros tiempos, conversaciones cuidadosas y abiertas al desacuerdo, al conflicto, a las ideas “sin rumbo”, al bombardeo y autocuestionamiento; a la detonación que hacen las palabras y que puede resultar en lazos de reconocimiento o en derrumbes de convencimientos.

Desde este lugar surge el taller Re-conociéndonos en la diferencia, un diseño entrañado en el contexto colombiano (aunque podría ser replicado en otras partes del mundo), como respuesta disruptiva contra la violencia y el miedo que nos atraviesa más no determina. Este taller es un cuestionamiento constante hacia la manera en que nos acercamos, conocemos e interactuamos con lxs otrxs, una propuesta que busca la revelación de las lógicas que subyacen los imaginarios y prejuicios que determinan nuestros encuentros y desencuentros, nuestro rechazo a la diferencia, miedo y en últimas violencia tanto hacía lxs otrxs, hacía el territorio en que habitamos-somos como hacía nosotrxs mismxs.

El Armadillo surge en principio como propuesta de convocatoria para el taller RE, pero no es espejo del RE, es una exploración otra, un punto diferente del rizoma que surge del punto “anterior”; sin embargo, no es lo mismo, ni está desconectado, surge de la misma urgencia de reconocimiento y revelación. Ambos son un llamado a la creación autónoma, reflexiva y cuidadosa, aunque desgarradora e incómoda de otras narrativas, de otras ficciones de vida que nos permitan otras cotidianidades, presentes, y vida en la vida. La destrucción consciente pero cuidadosa y amorosa de lo que nos han impuesto y hemos entrañado hasta hacerlo parte de nosotrxs mismxs, creemos que es una manifestación de cuidado y apertura urgente en estos tiempos de miedo a la diferencia, que incluso le teme a la diferencia que somos.

Hilos lanzados al aire, libres para tejerse, y por qué no, enredarse entre posibilidades.