Lost and Found, and Lost Again, While Addressing a Herd of Elephants in the Room

Since autumn 2022, we have been developing a cartographic portal in a partnership that consists of one collaboration between three artists (Ciel Grommen, Maximiliaan Royakkers, Clémentine Vaultier); an artist duo (Vermeir & Heiremans); Elephantmappers, a Brussels-based cooperative working with open-source software; and two small artist- or curator-run organizations: the Brussels-based nadine and the Danish organization f.eks. The mapping protocol in the making needs to reconcile curatorial and artistic perspectives as well as different organizational forms. This text voices our collective concerns that are guiding an ongoing working process that could generate more agency for our transdisciplinary artistic practices.

Finding a balance between a visible agenda and its invisible counterpart, which is inevitably reflected in the practice of mapmaking, our collaborative endeavor aims to incorporate a practice of “countermapping” that continuously code-switches between the geo-localized god’s-eye view of mapping and a critical disruption of mapmaking that can subvert an idealistic but nevertheless brutal ambition to model the world after the beliefs of its makers. Our countermap needs to be able to account for what we all find important within our embodied art practices: the flow of time, narratives, histories, and relationships—in short, situated knowledge derived from direct observation, emotions, collaborations, discussions, etc.

All current partners are mostly working with processes in public space. We want to accommodate a wide variety and range of people, places, things, archives, etc. Below we discuss a process of mapmaking that aims to make visible our interconnectedness as well as our collaborations and communications with each other. In a series of semifictitious dialogues, we elaborate on what we find inspiring or relevant to share. These conversations reveal the limitations of our ambitions and the points where those ambitions converge. They will briefly address some of the details and practicalities that we are dealing with in a way that can transform what can be considered a “dark” infrastructure into a relational one.

Prelude: Three Conversations on Our Nomadic Journey Towards Mapping

1. Learning through the Soles of Our Feet: Loes Jacobs in Conversation with Vermeir & Heiremans

Vermeir & Heiremans (V&H) : Loes, as a laboratory for contemporary arts, nadine has been working with ephemeral practices for a long time. Why does the organization specifically support these types of practices?

Loes Jacobs (LJ): Around 2014, nadine was connected to a group of Brussels-based artists who were very active in public space, using walking, traveling, or mobility in their artistic practices as methods or ways to create, and in some cases connect to, an audience. That year we initiated the Wandering Arts Biennial (WAB), a platform where artists could gather and share these practices but also find an audience to present them. Today we support artists in many different ways. We have our exhibition space, we organize curated platforms and timely gatherings with peers, and we give financial support

V & H: Nadine being one of the partners of the mapmaking process, why do you think this might be a fruitful journey for the organization and for yourself?

L J: The initial reasons for nadine to join are twofold. As mapmakers ourselves, we are in need of a unified identity for our maps. We need a user-friendly digital tool that can create maps on demand for communication purposes. As an artistic platform, we support many forms of mapmaking, from geo-located walks to nomadic protocols. The idea of a shared tool, one that is transparent and adapts to the reality of artistic representations and collaborations within a 2D digital framework, is something we absolutely want to support. For a structure that works with nomadic practices, the creation of a tool for mapmaking, and therefore, inevitably, archiving, is interesting. It raises pertinent questions about the very nature of ephemeral nomadic practices and their existence off- and online.

But I am also curious to hear from you . . . How do you link your ongoing walking practice 7 Walks with an interest in mapmaking?

V & H: The experience of walking together, sharing a space, and entering into a conversation with the public is central to our walking practice. Inspired by its rich history in the arts, as well as in literature and philosophy, walking as a performative method balances between artistic, educational, and flaneurial practices. Next to a physical way of being in the world, walking also creates a shared space in which the questioning of apparently fixed ideas becomes possible. We have the impression that participants speak more freely. They find themselves on a more equal footing, which is a sound basis for an exchange of ideas. Walking allows us to involve the public in the process and research from the very beginning. The public is invited to add their own stories to the walks. They become cocreators of a form of “situated knowledge.” We come from a practice of filmmaking. Walking has freed us from the production constraints of filmmaking. We wanted to loosen control of what form eventually would emerge from the walking process. But in the end, there have been so many interesting site-specific discoveries, encounters, and discussions that we thought it was a good idea to be able to share these beyond the people who were walking with us. The mapping tool will allow us to revisit some of the ideas and narratives.

L J: I remember meeting you to discuss a possible collaboration with nadine. That first encounter could have lasted many more hours, as we discovered a lot of overlaps in methodologies and points of view on how to represent ephemeral practices in the cultural field. With the methodology of walking being the common thread, and the direct involvement of the public, what you just said—people becoming cocreators or companions in the research—those are also characteristic approaches for nadine. As an organization, it is important to find the right language to invite the public to take part in such a walking practice. Next to this participatory and cocreative practice, we also communicate about walks that were created for an audience to experience after the creative process has taken place. They can be activated with or without the artist present and with one or more people “reenacting” the walk. Of course, in all cases, these are experience-driven artworks. They exist because they are performed. The more they are walked, the more layered they become—in time, in narration, etc. These walks could also have a “life” in a mapmaking tool, at least I imagine it would be interesting to communicate about them through this tool.

V & H: In our practice, we walk through a city’s material infrastructure and link those material “anchor points” to an “intangible heritage,” the ideas of philosophers, politicians, and artists who lived and walked in the neighborhoods we traverse ourselves. We see this as somehow giving a “voice” to a common “resource” in public space. In 7 Walks, we focus on property relations, specifically of water as a natural commons. In parallel to that, we look into property relations in the field of art, which we consider a social commons. By traversing a physical space and narrating its visible and invisible resources, we hope to trigger people’s imaginations and open discussions on what we value.

L J : I think the nonhierarchical perspective is very important here. It makes it very different from a classic didactic guided tour. And I must say the historical narratives you are able to dig up are often surprising and always a trigger to speak about contemporary issues and questions

V & H: They often also surprise us and sharpen our thinking. One of the most inspiring figures for our walking projects is the Brussels-based French anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus (1830–1905). He practiced an “intuitive geography,” a look-and-see geographical method that was in direct contact with its environment. Geography takes up a central role in alternative learning. The great tradition of anarchist education swears by the axiom that the best learning happens through the “soles of our feet.” Reclus also triggered our interest in cartography. In his lessons, he refused to use two-dimensional maps. Instead, he started from the observation of the nearest stream, as he recounts in his book Histoire d’un ruisseau (1869). Anarchist geography saw maps as a means of creating subjects rather than empowered citizens. Reclus wanted to ban 2D maps in schools, on the grounds that the projection of the globe onto a flat surface causes distortions, contributing to a Eurocentric vision of the world. He preferred working with globes. Maps were and still are linked to state, power, and capital.

L J: The refusal to use 2D maps reminds me of the maps we distributed with the wandering practices during WAB. Not all these practices work with geo-located points on a map. There are many artists who create protocols for walking or moving through public space. The starting or ending points are unknown, and people navigate following certain protocols, like descriptions, counting mechanisms, or even using tools such as dice to make decisions. It will be a real challenge to “implement” these walks in the mapmaking tool we are creating.

2. A Conversation on Atlas of Ovens: Ciel Grommen, Maximiliaan Royakkers, Clémentine Vaultier

Maximiliaan Royakkers (MR): Atlas of Ovens is a relatively new collaboration. Clémentine, you—as well as Ciel and I—have been interested in heating infrastructures for some time now and have elaborated on this topic in research and projects in the past. Through our mutual engagement with Emptor, a research trajectory on the notion of property in the arts initiated by Jubilee, a Brussels-based, artist-run platform for artistic research, we got to know each other’s practice in depth, and it had become clear we shared similar sensibilities and overlapping interests. I am curious to hear from you: Why you were interested in bringing our practices together?

Clémentine Vaultier (CV): We found out that the three of us were collecting different documents of heat containers: drawings, plans, sketches, pictures, technical descriptions, and anthropological reflections, as well as documentation of our own experiments. You, from a more architectural perspective, and I, through my ceramic practice. I think this overlap of viewpoints was opening up possibilities to address heating practices in a wider sense, from the production of objects and materials to working on heating bodies and spaces, etc. At the same time, all three of us had already visited and used quite a few oven infrastructures. We had exchanges with people that work with them, which proved to be incredible learning experiences. I was interested in building and using ovens collectively as a way of sharing knowledge and forming relations by gathering around the fire.

Ciel Grommen (CG): The starting point for me was this gesture of sharing. We share references among ourselves but also use the act of collecting documents as a way to connect to others, to their knowledge and practices. In addition, we want to open up our encounters with ovens and their multiple uses by organizing visits that intertwine different heating contexts and by using these infrastructures collectively.

MR: In our conversations, we tried to elaborate a different viewpoint on heat containers. More than just technical shells guiding material transformation processes, we saw ovens radiating towards communities and possibly supporting new forms of relationships. In that sense, Atlas of Ovens is a way to explore the notion of relational infrastructures by elaborating on the whole web of actions that aren’t usually taken into account, like for example, invisible work, energy consumption, and legal aspects, but also rituals that sustain an oven.

CV: When discussing the project with Vermeir & Heiremans, the term “relational infrastructure” also really spoke to them. We shared the question of how to enhance collaboration, to show the ecology of relations and not only isolated individual objects. For the Atlas project, the term operates more and more as the goggles to look at objects and their radiations, which is also an aesthetic question that, as artists, we want to approach.[/commentable]

CG: I wonder how our reflection on the development of Atlas of Ovens will advance through our participation in the mapmaking project, and if it would have taken a different path if the map hadn’t been part of our development of Atlas from the beginning?

MR: Well, I remember that although there was no necessity from the start, we saw our involvement as an opportunity to publish our work in a dynamic and open form for a wider audience. Over time we understood that the map is something we had already conceptualized as an essential part of our project, without naming it as such: from the beginning, we thought about a type of territorial archive of the places we wish to explore, linking ovens and the narratives we construct around them. The fact that Atlas is already a kind of map erases the borders between the two projects and offers an opportunity to reflect together on questions related to this underlying term of relational infrastructures.

CV: Yes, for me the main question at first was the restrictions coming with the design of a tool that functions for different practices. But it became clear that this overlap of practices also came with a densification of exchanges between partners and opportunities to refine the what and why of Atlas. Of course, it urged us to make choices, but I have the feeling that whatever direction our project takes—from writing grant applications to organizing events—we are always very responsive to new questions and situations that we come across. The fact that we are constantly discussing our steps and working with the excitements of others—the availability of resources shapes the trajectory of Atlas in a quite organic way.

MR: The interest in the map as well as in Atlas lies in the journey we take to design them. It is about creating an inspiring relationship and putting care into how we sustain those connections. In the case of the research related to Atlas and also the map, it is about going beyond the functionalist approach to a tool, reappropriating it as an engine of meetings, discussions, and possible constructions of narratives.

3. The Voice of Seven Elephantmappers

—Elephantmappers is not our real name, it is a fiction. It expresses our willingness to build a bridge between our mapmaking practices and the “elephant in the room,” referring to an obvious problem or risk that everyone sees but no one talks about or feels comfortable discussing openly. In social interaction, it means that something as obvious as an elephant can be hidden by implicit codes of conduct. As a cooperative we chose to work with open-source software. This fictional name refers to a public letter to cultural institutions written by the association for art and media Constant. The elephant in the room for Constant relates to cultural institutions confining their collaboration tools and digital archive to tech giants.

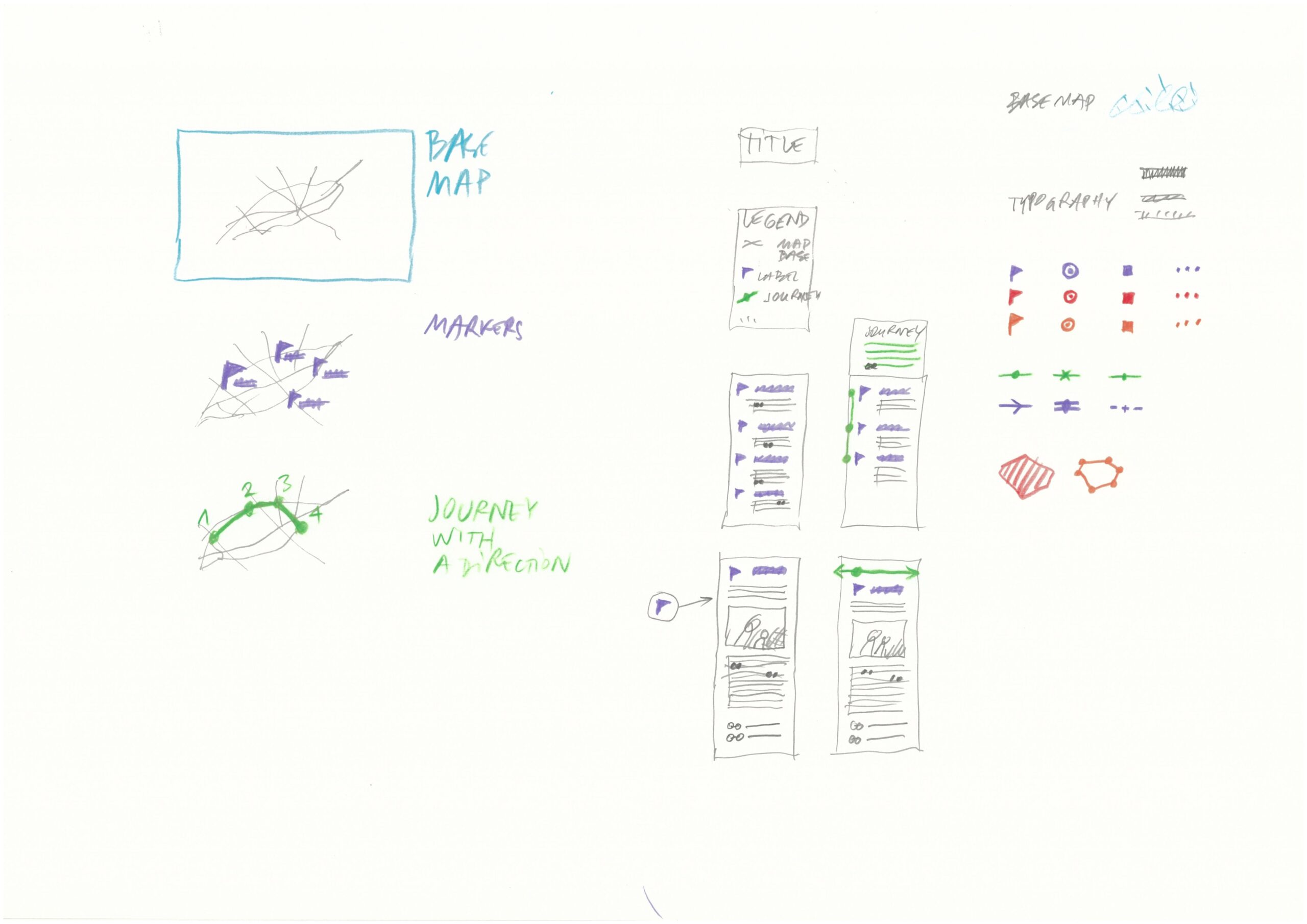

—In our work, we try to look at this elephant in the room. Porcelain Lanes is a good example. It is a fictional name for an existing open-source mapping software that we developed. It stands for an open and collaborative approach to subjective mapmaking. This approach consists in the conception of protocols for collecting and generating data embodied in various cultural contexts without erasing that contextual information or specificity. Basically, it is a geo-referenced blank page on which you start building a map from scratch. The construction of the tool has become a pretext to gather all kinds of cartographers around the table. All the cartographic tools we developed are now activated in workshops intended to support the implementation of observation campaigns, the collection of data, their visualization, and the publication of maps. Through these devices, we encourage the creation of shared, specific, situated knowledge about spatial/territorial issues by and for the subjects involved in the collection of data, the creation of maps, and their publication.

—In fact, for us, the real issue about mapmaking as a dark infrastructure is authorship. Who is the author of a map? Those who order it, those who pay for it, those who trace it, those who use it, or those who are embedded in it? The map remains a matter of power and a representation of society with dominant and subordinate actors. Choosing the map as a mediating tool between artistic practices and the territory is not an innocent game. Neither is the way in which this tool is mutualized between different artistic practices. It is based on existing collaborations and financial necessity, and in that way, by joining forces, it also raises a political agenda. This is what interests us as a cooperative of cartographers. We design maps. We are those who remain in the shadow, but without whom the map does not exist as an object. This shadow is our essence. As a craft collective we are not looking for fame, nor do we put our name on a work of art. There is no claim for power. What drives us is the social ground in which our craft and know-how are embedded. In this way, we also create a geography of relations between different worlds, using the same mapmaking tool to assess the way they relate to territory. So the power of anonymity is also a way of embedding our work in the territory.

—Coding is a specific language. Like any other language, it moves, it lives. The map is a tool built through coding. It’s a bit like arriving somewhere, but you don’t speak the language. You need a guide, but that guide chooses what to show you and what not to show you. In a sense, it is a matter of trust. Although what remains at the end of a journey within a territory is not the way of possessing its knowledge but the way of experimenting with it. So you may have learned a few words of code and forget them after a while. What you will not forget is the relationship you are building with this tool and with us as its designers.

—Although the artistic world has its own mode of operating, putting a sticker on who is an artist and who is not, it also offers the ability to work in an open, transdisciplinary mode. Being a partner in an artistic project is a way for us to experiment with what we would not be free to experiment with in any other institutional context. However, reconciling the different socioeconomic modes of operating in this project with their own conditions of production seems to be an issue that needs to be addressed. From a financial point of view, there are two aspects of our contribution to the project that we would like to detail. Our cooperative does not structurally receive public funding. The people who work with us know that they will have to pay the equivalent of what a self-employed person needs to live in society. We realize that the other contributors in this project, artists and researchers, have similar needs that at this point are not fully met. However, we bring to each new project what we have built up over a long period of time with other institutions through the open-source practices initiated in other projects. So there is a mutualization of costs that takes place across different projects. This limits costs, avoids starting from scratch, and ensures that the code of this mapping tool survives and grows in a way. On the other hand, we have decided to work on this project together by also investing extra time and financial resources in it. In that way, we are not only those who design the map but also among those who pay for it and put it to value by building further on it in the future.

A Conversation on Dialogues

—From which perspectives will we speak in this text?

—Maybe we need to assume multiple perspectives?

—Are we then mapmakers, users and readers, and public at the same time? A complex layer of voices that offers different perspectives. I think we need to be partially fictitious characters. We are ourselves and multiple selves at the same time. We embody individual artists, collectives, organizations simultaneously.

—For me, we not only fictionalize ourselves as characters, I think time also needs attention in our writing. Our dialogues are giving insight into a process, and we can do that by jumping to different moments in that process. We not only speak about developing a mapmaking tool but also about the ambitions we have and the hurdles we met and will meet, etc.

—Shall we use the reports of our meetings as a starting point?

—Should we then randomly choose names from the people in our partnership and let them “speak?” Maybe it is not important who said what at which point, since we worked on this as a collective of persons. The ideas and discussions and reports, all of them we have created together. They emerged from our discussions and are shared.

—But isn’t that contrary to what we have called a “federated” approach? Isn’t it better to talk as “we,” and from that point of view take the reader through the journey we made together?

— “Federated” means that we work together, that we mutualize, but that our voices—as individuals or organizations—do not get smothered under one collective voice.

—The “we” that you refer to does not really “exist,” does it? We are all different voices. I think it is necessary to differentiate. This also shows that we are still discussing, disagreeing, agreeing that we are indeed in the middle of a process.

—I agree. Let’s go into a polyphonic mode, each keeping their own voice . . .

—But can we then still create a fictional dialogue?

—Our polyphony can be partially fictionalized. If we are transparent about this, I don’t see a problem. Let’s “gamify” our conversation.

—In that case, do we also fictionalize the possible dissonance between us?

A Dynamic Archive

—One of the initial reasons to develop a mapmaking tool is to have the ability to archive intangible artistic practices and, in that way, generate more visibility for them. Taking the form of a walk, a bus- or bicycle ride, they often are very momentary. Being site and time specific, the momentum of the work is often that particular shared moment, the shared experience of a place and a narrative with a public. In many cases there is little or no documentation. For those who were not there, our practices remain invisible, almost nonexistent.

—But don’t you think that what makes our practices more visible might at the same time render them as something static? For me, the map is not our practice. Our practices are in the landscape, between the chimneys and ovens. They are situated in the places where we are researching, walking, discussing . . .

—I am not so interested in preserving or archiving these immaterial gestures so that people can reactivate those gestures. Why should these practices need to stay around forever?

—I find it strange that we are talking about archiving as if it exists only in a fixed, static form. An archive can also be dynamic. It can be activated, reused, messed up, and even destroyed to create something new.

—That is what our map should make possible. It should not be a static archive but evolve, create dynamic relationships, new projects . . .

—At one point our ideas started to evolve from a map as an archive of our practices to the notion of a more relational infrastructure. We said that it would contradict our embodied practices for the map to be reduced to a geo-localized archive of images, documents, text, etc. We need a translation to a map that can account for aspects other than geo-localization, aspects that are important in our practices, such as the passing of time, the encounter with other people, the possibility of telling stories, generating narratives, activating histories, the natural or cultural elements we engage with, the particular sounds and smells.

Relational Objects

—Since we have limited knowledge of code, which results in a deep gap between our different practices and the Elephantmappers, the only thing we can do is have trust in what they do.

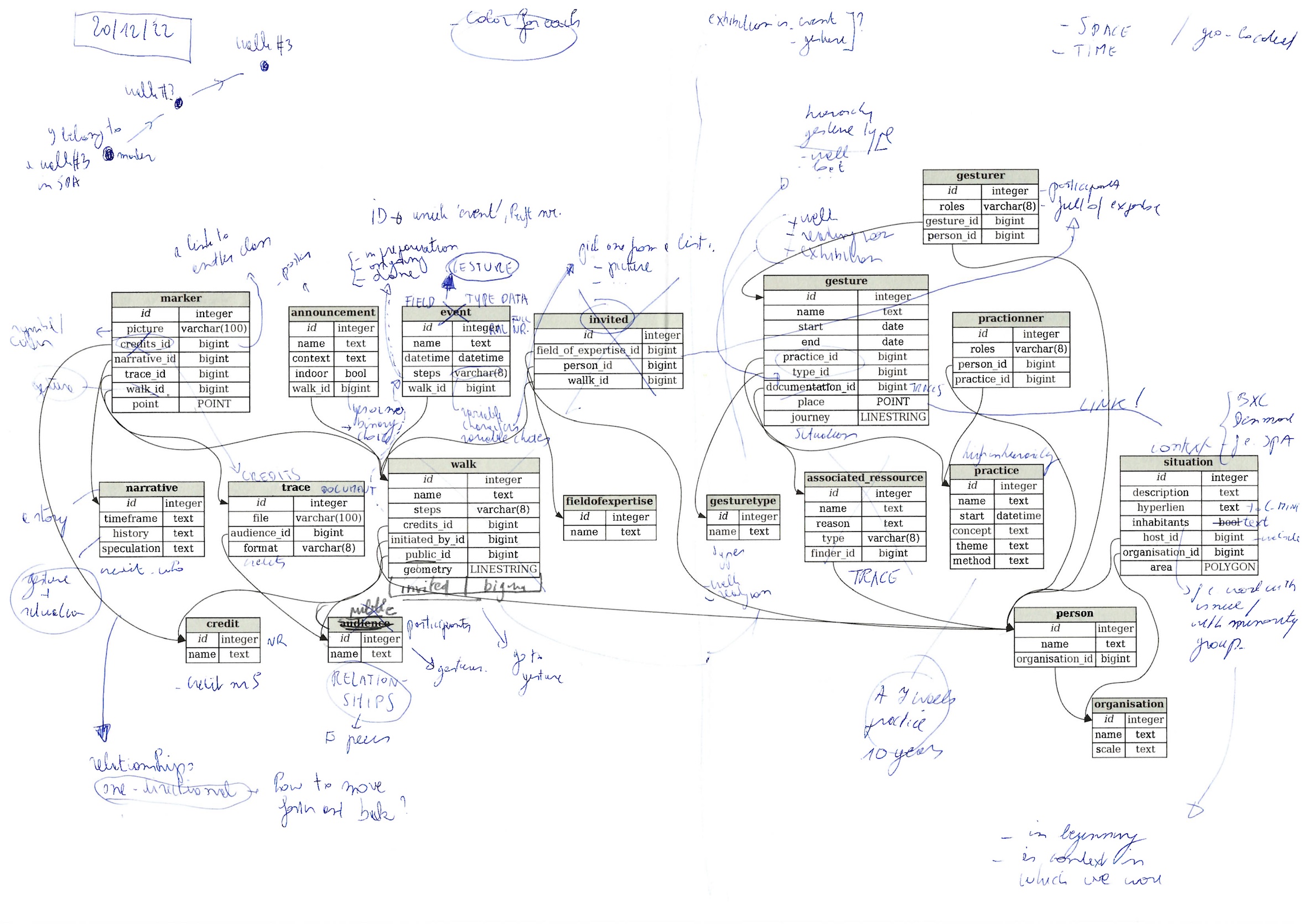

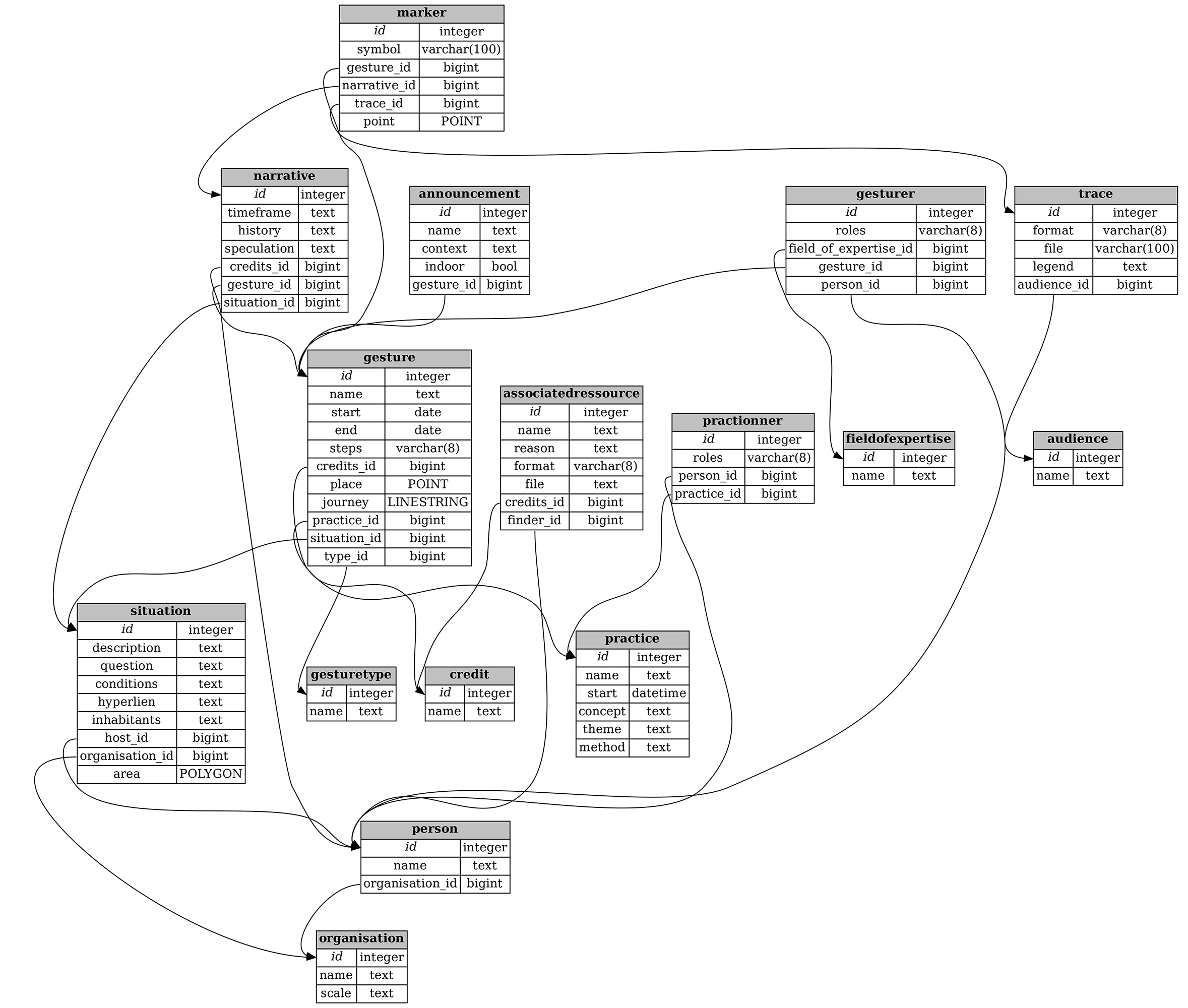

—Sharing the making process of an interface eases the understanding of the infrastructure and in the end allows for a common language to be found for all involved. Trust is an important factor in this process, as not everyone needs to master all knowledge yet must be willing to share their knowledge. A map is not only a 2D representation of space—it is also a container of code with an attached decision system of representation behind it. Collectively learning about what mapmaking is starts with what we want from a map and not the other way around, e.g., what a map already is and what it can be for us. Designing a mapmaking tool therefore brings to light the structure behind it.

—Yes indeed, we’re in the middle of a process here, and a not-yet-knowing where we are going. We’re trying to communicate and bridge a knowledge gap. To the many questions we still have, there are no clear answers yet, but we are on a road together.

—I found it quite intriguing how the workshops not only allowed me to better understand our own projects but, in the same gesture, relate them to a map. What should go on the map? What do we leave out? In a second instance, the exercises also seem to clarify what our different projects concretely share with each other.

—The workshops aimed at shaping a common vocabulary for talking about things and taking into account the implications of talking about one thing rather than another.

—One goal of the workshops is to identify different layers and elements, to visualize the materials that are in front of us. The idea is that we discuss the mapmaking imaginary we have in mind and from there, together, model them into different “types of things.” The structure that the Elephantmappers will develop will define the future possibilities of the mapmaking tool. The idea is to start from discussing the mapmaking imaginary.

—Our artistic projects consist in bringing different images together. So images should be contextualized. In the same way, an image as a link between two practices can be our point of interest. That way objects and pictures start generating alternative narratives, and the map starts functioning as a “relational infrastructure.”

—We highlight relations that start to exist between different places, between places and projects, between projects and projects, and between the different partners and practices. At the same time, our practices also have something specific to reveal about a place itself, which means they also remain singular approaches. It seems that we find ourselves in a paradoxical position, if not contradictory.

—Maybe at this point we can conclude that we chose to focus on highlighting the relations between documents. Documents only get a surplus value if they can concretize relations between the different partners. They become testimony of a dynamic, an agency that goes beyond one artist or one organization. The documents that are integrated in the map show relationships between our practices. In that way the documents are part of and generate multiple narratives rather than being merely one document in a database, which in the end is just an accumulation of autonomous documents. The documents in the map become “relational” objects.

Agency in Practice

—Another reason for creating the mapmaking tool together, which we have expressed quite often, is generating more agency for our nomadic practices. But I would very much like to hear what that means for every one of us here in practice?

—For me, “agency” implies the possibility of sustaining a practice. Will we be able to do the next walk, the next exhibition, research, workshop . . .

—Shouldn’t it mean more than being able to sustain our practice or our next project? Isn’t it also about creating propositions that strengthen the social fabric? Speaking about an impact on society sounds a bit static; the word “agency” has maybe a more active ring to it. That is my motivation to organize meetings with the public, to publish, to archive . . . and in the end to develop a mapmaking tool.

—I would say that “agency” implies a dynamic between existing hegemonic forms and alternative practices that do not reproduce these forms, and the economic conditions and working relations that go along with them. This can be considered within the art world but also in society at large, of course. It is the dynamic between “infrastructures,” institutions, conditions, social forces, and how people feel they can think and speak their minds and act upon them. These hegemonic forms define what becomes visible and valuable. You can reproduce those values and forms or counteract them, individually or collectively, and introduce elements of change.

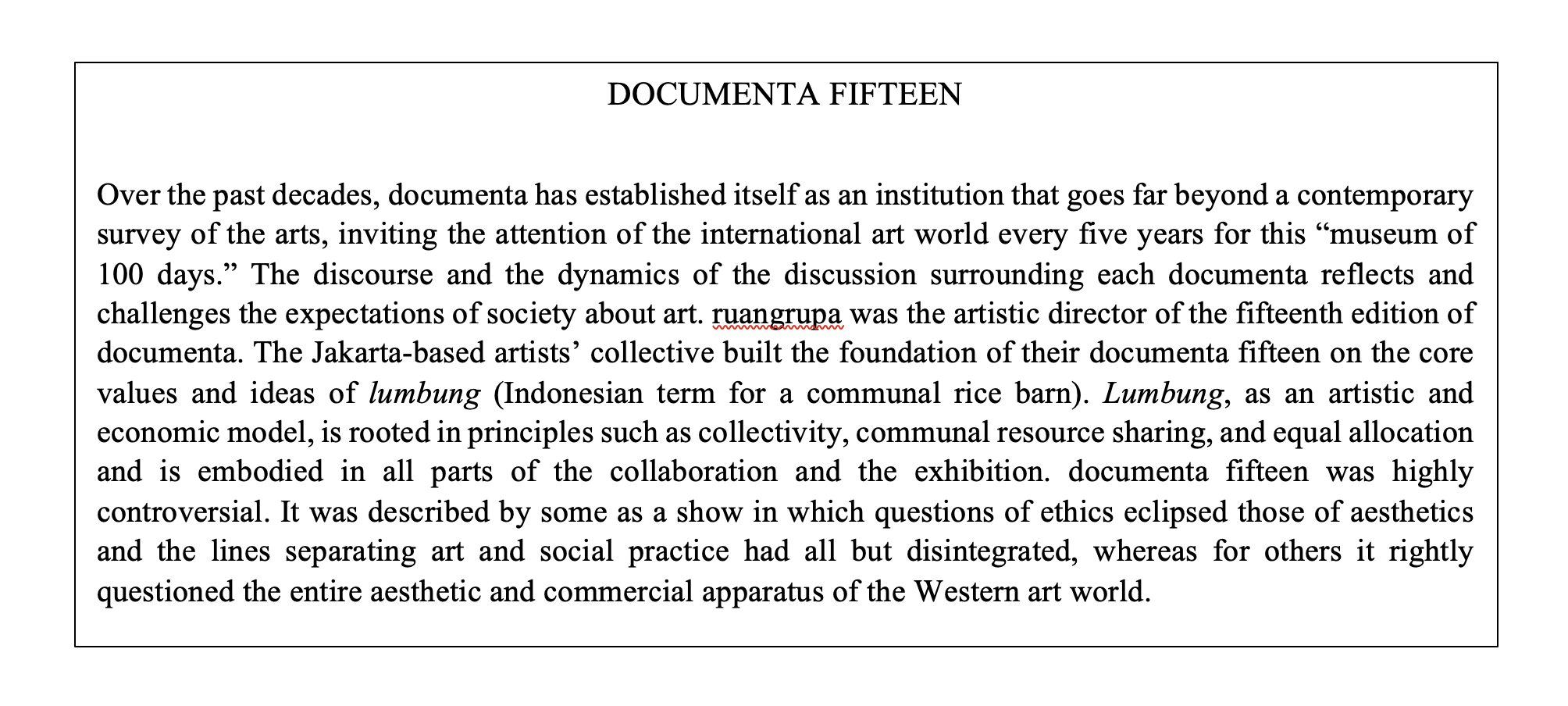

—I think about what happened at documenta fifteen, for example. The Indonesian collective ruangrupa brought in collective practices from the “Global South”—a problematic term—in a place that normally confirms the values of current gatekeepers, like the art market and its star curators.

—That is why the emotions ran so high. On the one hand, people were positively surprised at what and who they encountered at documenta. On the other hand, many collectors, commercial gallery owners, museum directors, and even artists did not want to visit, or when they did, did not feel triggered by what they saw in Kassel. For many, this edition was simply a missed opportunity, but actually I think it represented a fierce struggle about hegemonic values in art.

—Yes, indeed, who defines what art is and what it can be? What happened at documenta created a lot of agency for collective practices. It generated empowerment and visibility, created connections and relations, but will this renewed attention to alternative forms of organization lead to a sustained paradigm shift, or rather to the development of two separated art worlds running in parallel at different speeds? In the end this might not be a good thing.

—When we try to apply what we just discussed to our mapmaking endeavors, how would we then speak about creating agency through the mapping project?

—I think the map is an agent. It is an active tool that has agency itself. I see it as dialectical. It might change how we practice things, how we organize walks, for example, but likewise the different practices might change the tool. For example, if we organize walks that follow a protocol, how will they influence and shape the map? Mapmaking is also an ephemeral practice. It supports what we are doing and, at the same time, it cocreates our practices.

—Yes, that way we can keep it alive, avoid seeing the map as a “fixed idea.” When adding new practices, we create more layers, more visibility, more depth by connecting them to the other practices already present on the map.

—Good point. I would like to add that for me, one of the reasons to work on a collective map is exactly the collective agency we might generate through it. I don’t think we want to remain small, isolated islands of practices floating in a void. We spoke about the map only being a success, when we can go beyond merely transferring information from those isolated spaces, which could also be distributed through our individual websites and newsletters. If we could make our mutual relationships visible, create attention for each other’s practices and in that way distribute our shared values, that for me would be the surplus agency we can derive from this mapping tool!

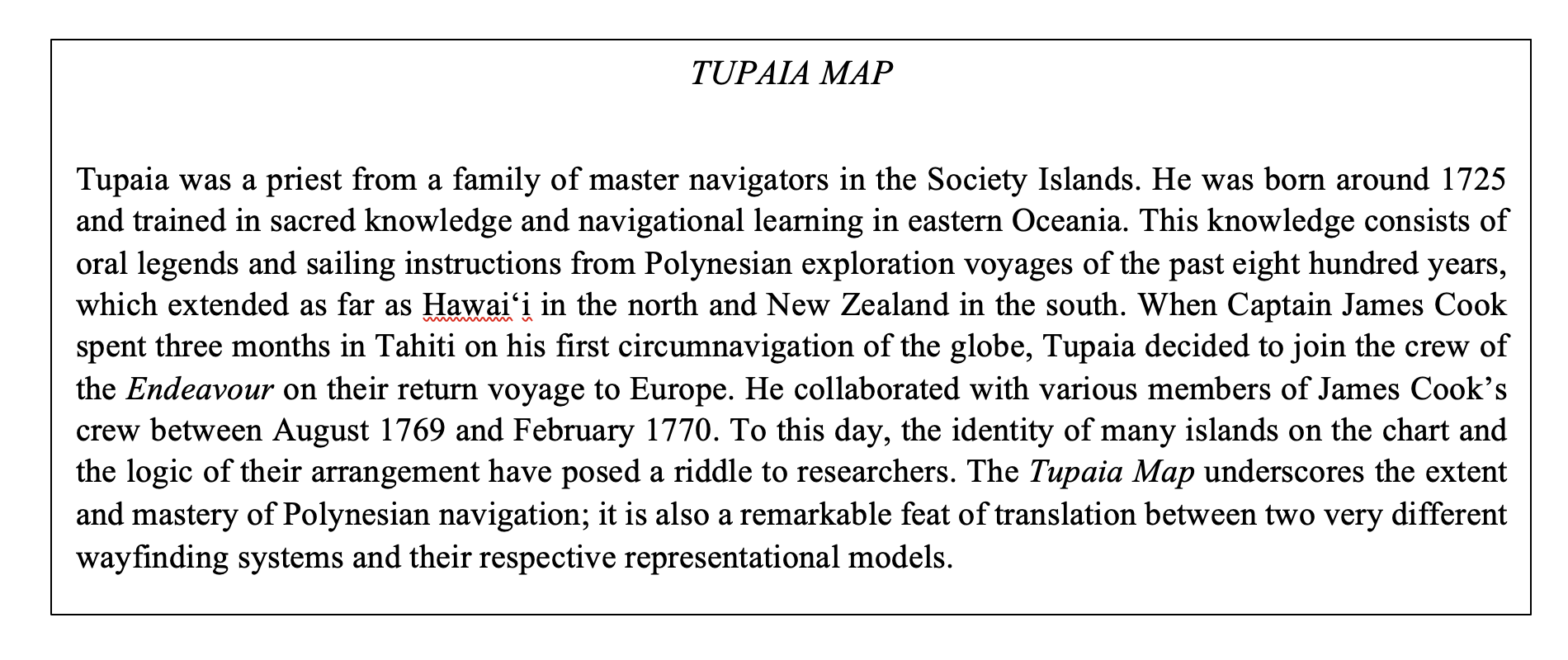

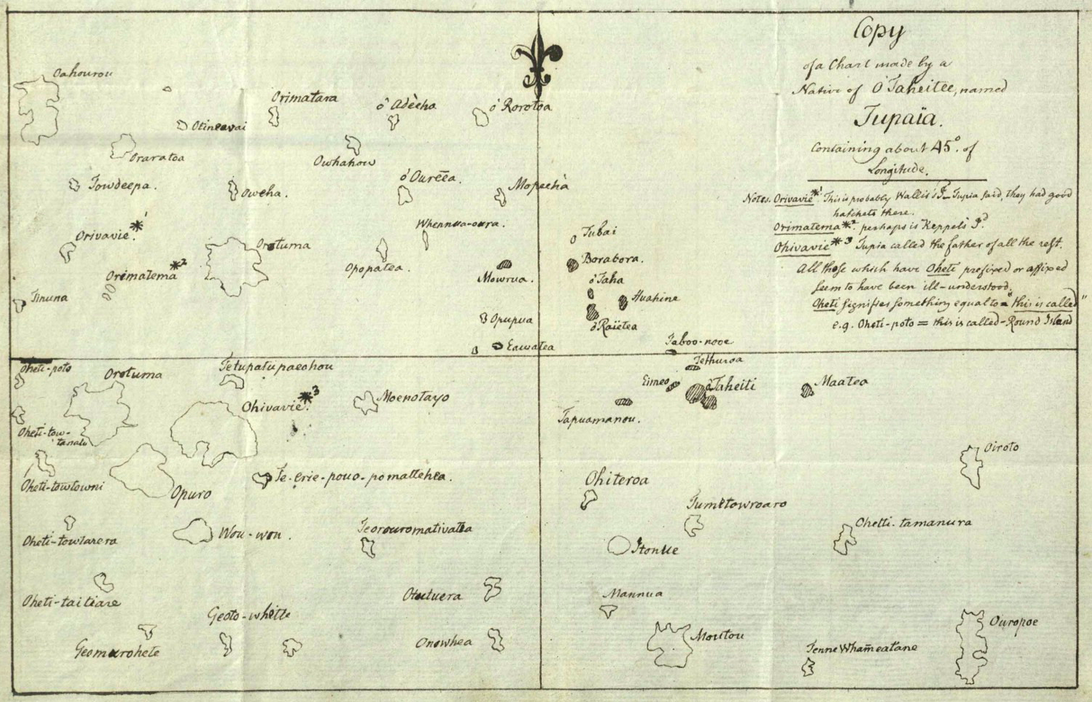

—For me, it is too black-and-white to think in terms of hegemony and counterhegemony. I would like to refer here to the so-called Tupaia Map that we discussed the other day (Eckstein and Schwarz 2019). Since we found out about this historical map, it is fair to say it has inspired us and guided us through the wild waters of collective mapmaking, so to speak. It is mind-boggling and has helped a lot, at least for me, to look at mapmaking differently. Tupaia was an eighteenth-century Polynesian master navigator who decided to board Captain James Cook’s ship Endeavour, where he collaborated with the crew on a map. What Tupaia did, in a critical act of agency, and which is so fascinating, was translate a hegemonic form of mapmaking into a new form, reusing and adapting for his own purposes the existing Mercator-style projection map that was set up by the crew. Tupaia is mapping and countermapping at the same time. It is the code-switching and translation of representational systems, the clashing of abstraction and embodied knowledges in one map. Tupaia transforms mapmaking into a narrative device, into what we’ve named a “relational infrastructure.”

—I can relate very much to that. As a cultural organization, we also see this as our task, these acts of “translation.” Walking practices are transdisciplinary practices, and the artists we work with are always exploring domains beyond the art world, like science, education, history, etc. These approaches, these meetings of different worlds, we also have to translate and communicate to the public.

—Yes, to obtain more support, more participation of the audience.

—Right, this type of translation is also something our map should do. Our ephemeral practices don’t move so easily in recognizable circuits and value systems, since the museum and art organizations have their specific production and distribution logics that do not necessarily fit our approaches.[/commentable]

—Yes, we can be “misfits” here. But we could also show how to use the big institution-production machine in a different way. For example, when we activated the interior setting of the Aalborg Kunsten Museum for one of our walks and presented a work from their archive, the museum was quite surprised that the public went along with what the curatorial staff initially considered a series of disruptive gestures. The audience loved the experiment! I hope our mapmaking can trigger discussions on openness to experiment, changing codes and norms, and question the frontiers of the art world. Like the Tupaia Map, I hope it will be a device to communicate, share knowledge about our diverse practices, and, yes, create agency, right?

—Our practices tend to call into question the framework or the infrastructure of the arts. They question the idea of the autonomous artist and the value systems that are attached to this notion. I’m looking forward to how the map will enable us to develop these questions together. I hope it will trigger more awareness, experiments, and in the end generate more hybrid practices.

On Dark Infrastructure

—There are multiple levels of darkness and how we could address them. There’s a potential darkness between all of us and possible future contributors and users of the mapmaking tool. And since not everyone masters code writing, there is a darkness in developing the code of the mapping tool. Also how the tool will be governed needs to be discussed. It is undeniable that a lot of things still need to be clarified. Where will the map be stored, for example, on whose server?

—Why do we talk about dark infrastructure as something negative, as a monster or an enemy? Can the “heart of darkness” also be a positive force? Can the Elephantmappers inspire us in that way?

—The workshops help to mediate between this language most of us don’t master and our artistic practices. Instead of being guardians of the code, couldn’t Elephantmappers be considered translators of the code?

—I think the darkness is not between us and Elephantmappers but rather between us and the “infrastructure of the digital.” Indeed, their work is all about translating the code, and thus rendering it more transparent, don’t you think?

—In our mapmaking, there cannot be full transparency. We are in the middle of the process and basically are still in the unknown. But maybe we can also see uncertainty as a potentially positive force.

—There is the dark monster of not knowing where we are going and the invitation to join the experiment. It counters the notion of “learnification.” It aims to go beyond the acquisition of certain predefined knowledge goals. Real experiments, drifts, or unplanned excursions, mistakes, speculations, and surprises. We are showing the process. We are allowing people into the kitchen when everything is still a mess.

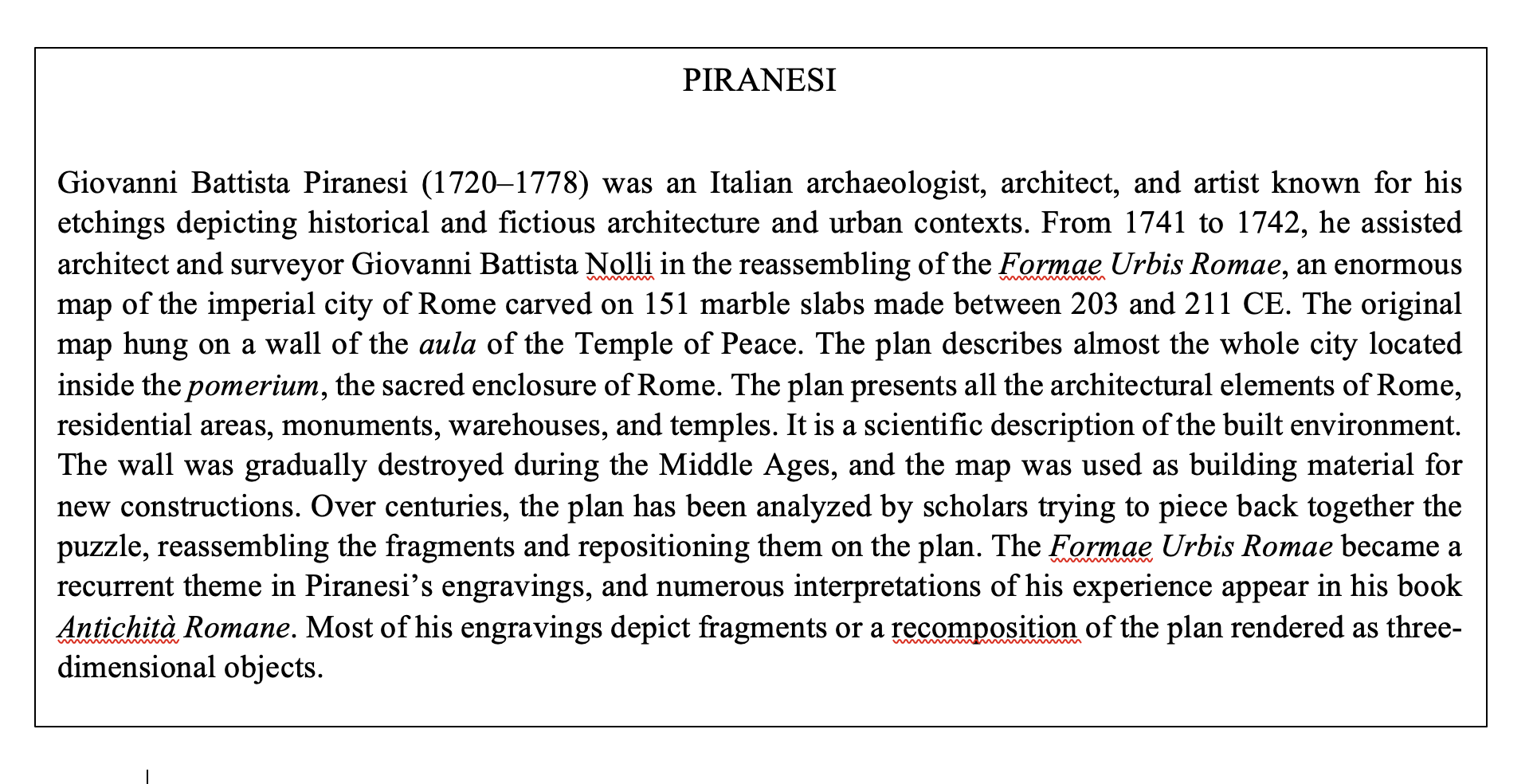

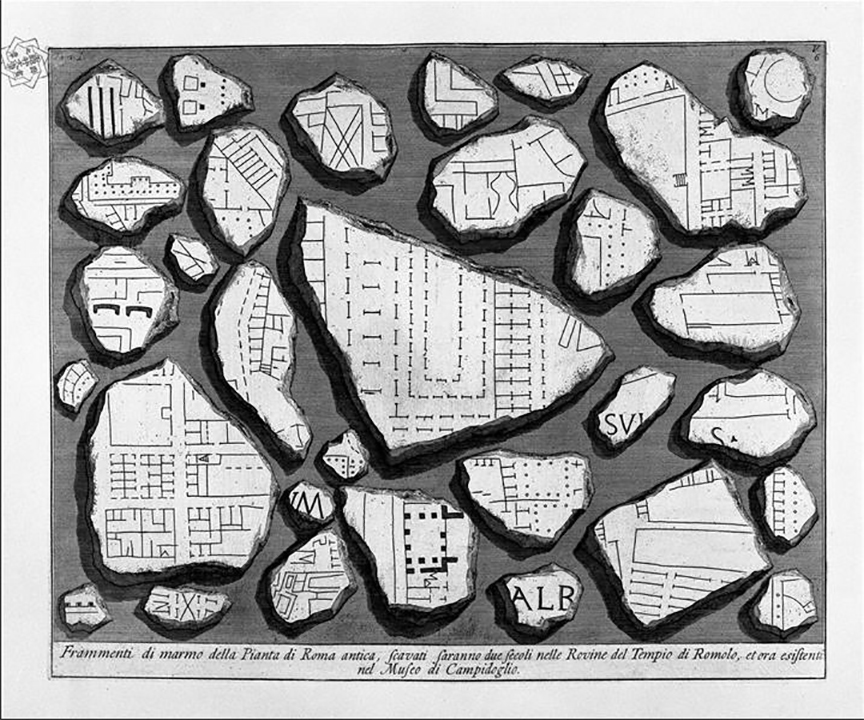

—Maybe now is a good moment to show you a map drawn by Piranesi. I have been hoping to work with it for some time . . . I think Piranesi’s drawings of a map of Rome are a good example to deal with the notions of incompleteness, speculation, and uncertainty. These drawings depict a map of Rome, once chiseled on large slabs of marble but subsequently fallen into ruin. Piranesi draws some “arbitrary” pieces of the map and arranges them onto a sheet. Different fragments of Rome appear like islands in a sea of white. Ordering them as shards on a surface brings together parts that in reality are actually far apart. Looking at this map, could we define the dark infrastructure as the white between the shards? It may be a good reference, because our partnering projects are sometimes geographically very far apart: Belgium, Denmark, etc. What separates the “islands,” I mean the different practices on our map, is a void, and at the same time this void is packed with meaning. Maybe it is here that our mutual relations can be situated. And that would be a positive value.

—I would focus on trust as a positive value within this darkness. We have to navigate through situations that are difficult to understand. We try to understand the coding and modeling of a digital map in the making, and we want to be confident that we can find ways to communicate, find ways to translate specific knowledge into forms that we can get our heads around.

—Yes, that’s a good point. For me, this would mean that we can be at ease with the unknown, the monster, the heart of darkness . . . The unknown is often obscured, and they say one should avoid it, it is too much risk, but trust can overcome this fear of the unknown.

—If trust comes from both sides, no? Why are we convinced that making a digital map together is a good idea, even if our relation to the coding is not (yet) transparent?

—In our lives we are confronted with the digital on a daily basis. It has become all powerful, a force that is all around us. We can no longer say, “Let’s go for a walk in the woods” without Google scraping the data of our whereabouts from our smartphones.

—Even when we are critical about the digital map, we cannot retreat from the digital as if it does not exist. Nevertheless, I think we can still try to practice “countermapping.” Our reading of the Tupaia Map offers an excellent example. Tupaia overrode the abstract, singular, god’s-eye perspective and placed the traveler, or his canoe, at the center of observation, with the world as a dynamic whole around him. The navigational chants from his ancestors would guide the traveler, together with what would constitute an embodied practice, the observation of the journey of stars, the sun, birds, and fish. But what is truly amazing is that the new map he created was not an act of sabotage of a hegemonic system but an attempt at communication, collaboration, and translation between almost incommensurable knowledge traditions. The map was jointly worked on by Tupaia and Cook, trusting that knowledge could be conveyed through this sustained collaboration on this complex task of mapmaking and navigating the ship at the same time. For me this is clearly an act of creating agency, an act of collaborative knowledge production, something you can not achieve individually.

On Openness and Enclosures

—We want to create a mapmaking tool for the longer haul, and also one that functions internationally. However, we should be aware that we, as the coauthors of the map, can find the tool we are designing very effective and inclusive for our goals, but that from the outside it can be seen as rather closed off. How to invite other possible practitioners, users, viewers? Should we define a set of rules for that?

—Yes, all this raises the question of how not to become too self-referenced. How can the mapmaking tool remain open to new contributors? How to create a “commons” with clear rules of use, content, access?

—Should we not make the map accessible to all possible contributors?

—That is a difficult question, but I would say access has to be conditional. We don’t want to monitor the map continuously for hate messages, etc., yet we want to keep it open for new practices to join based on the content they work on, the methods they use . . .

—Is it not a contradiction when we say that we do not need to be transparent about the mapping tool and at the same time claim that we try to avoid creating new enclosures?

—Transparency is not synonymous with openness and equal access. As we said before, we do not need to be totally transparent. We do not need to know everything in advance, and at the same time we do not need to show all our tactics and be open about all our possible agendas. But in my opinion, this does not necessarily create an enclosure.

—Thinking of “enclosure” in our project, for me, is about a digital environment, a place with an “in-crowd” where everybody speaks a common language, call it “jargon,” “code,” etc., and that language stays in that place. The only way in or out is a gateway called “interface.”

—Indeed, how addressable are we in this map? I mean to whom can other potential users or even the visiting public address a question? Who is responsible? Who can you ask if and how you can participate in using the map, as a visitor or as a contributor, for example?

—We know that immaterial commons, such as the digital map we are developing, have very different needs from natural commons, as they do not have to be protected from overconsumption. On the contrary, the goal is to expand the resource in quality and time as well as expand the flow of knowledge produced, yet protect it from improper use, like hate speech, as we said.

—But when you talk about rules, who is going to implement those rules? Commons can also become unbearable when there is too much social control. And next to that we need to discuss the economic conditions that allow these immaterial commons to thrive. How can work already done on conceptualizing the infrastructure be recognized? How do we organize labor involved in running the mapmaking tool, such as uploading content but also technical maintenance? What do we want to do with licensing? Can we consider a revenue model?

—Indeed, I also find it important to bring invisible labor to light. The so-called care tasks, like coordinating use of the tool, communicating, and organizing meetings, even solving conflicts . . . should be acknowledged by the “community” of map users. This type of “care work” is done for the benefit of the collective of users and for the individual practices in it. Everyone should contribute to a commons reciprocally, and possible surplus generated should mutually benefit all the contributors to those values.

—We could say that this horizon will open itself to us as our journey is progressing . . .

A Map as a Relational Infrastructure

—Can we talk more about the relational aspects of our mapmaking endeavor? How do we define them?

—You can look at the map from a technical point of view or from the perspective of the relations that form around it, a relational point of view. I like this quote from Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval: “we forcefully assert that only practical activity can make the common, just as it is only practical activity that can produce a new collective subject” (2019, 28).

—From my experience, editing and publishing a book is a real relational endeavor. It creates a momentum of knowledge exchange. The map as a publishing tool permits us to extend this process. The use of the platform requires the participants to continue exchanging and relating.

—I agree. For me, the most interesting characteristic is the incompleteness of the map, the possibility for it to change, evolve, grow—the unknown new narratives and partnerships that can originate from it.

—How can thinking about the Tupaia Map help us to transform our map from a mere tool of geo-localization to a tool that can account for relations and narration? Tupaia’s ancestral oral stories helped him to navigate. He made a map for Cook that is a storytelling device. However, his ancestral wayfinding did not need a map; the stories were enough, together with the embodied knowledge he derived from the waves, the sun, the stars, the flight of birds . . .

—What I found interesting about the Tupaia Map is that some islands appeared twice on the same map, which from a Western viewpoint is illogical. But his map showed how the same islands could appear in different voyaging chants. His map could not be understood as a singular spatial arrangement but as a sequential narrative of different voyaging routes, ultimately creating a visual palimpsest and showing their interrelatedness.

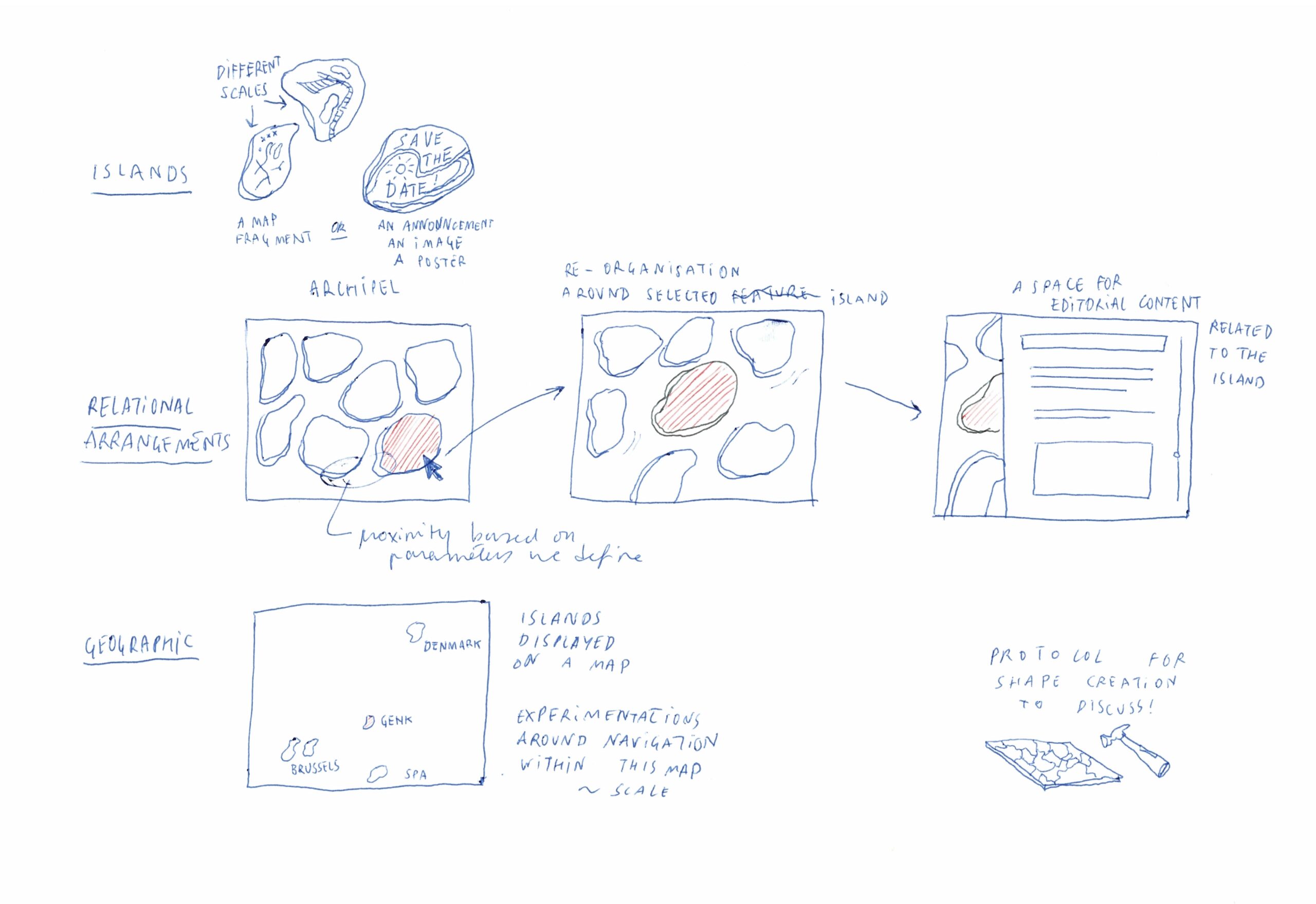

—I thought that on our map, a city like Brussels could also appear several times. But the perimeter of Brussels, as a so-called island, would that be different according to the project that is depicted?

—How will we define the border of the “islands,” the different locations where projects take place? Would different islands overlap?

—Indeed when imagining our different practices, and the projects within these practices, as singular geo-located fragments of a map, when organizing them in the same closeness as Piranesi did with the fragments of the map of Rome, we would have a tool that would highlight the relations between the islands of our practices, what we called the agency of the “white space” in between, without losing the option of using the map as a public tool for orientation.

—Would it be interesting, or even possible, to organize the islands of our map differently every time by choosing certain relations to stand out more? E.g., when I want to see a geographic ordening, or if I want to see a thematic ordening, or an order according to the format of the practices: protocols, guided walks, installations . . .

—So the general map would not have a fixed form but would be dynamic and adapted to the user and viewer? I’m wondering how this would reflect the relationships between us? During the process of discussing the map, and during the workshops we already had together, what became more and more a priority was to make our interconnectedness visible. Next to visualizing our collaborations and communications with each other, it was about building an infrastructure for commoning and mutualism.

—We spoke about the joint production of a “value common” when working together.

—Right, but then we also have to talk about possible “value dissonance.” And we have to say that we are not there yet; the map is still only there in our discussions. Will we agree on its value once the code is written, and it starts to function . . . when it becomes concrete?

—There are still more questions than answers, as we are in the middle of the process of trying to create a mapmaking tool together. Can we say that we already achieved another level than a purely functional map? Indeed, we have been discussing a lot about agency, collaboration, creating a federated infrastructure without losing our “individuality,” but trying to find common values, aiming for cooperation, mutual support, and emancipation.

—In the text we are writing here together, we are also opening up the process of collaborating. We are trying to find out what it will become by doing this together. We try to find common goals and values, working through the different ideas and visions, frustrations and disagreements, etc.

—This is a strong and vulnerable position at the same time.

At the moment of publication of this text, a prototype of the mapmaking tool has been published online. The tool is named Eavatea. It can be consulted on https://eavatea.jubilee-art.org/.