Of Buffalo . . . Notes from the Field

(Sustenance | Settlement | Social fabric)

"Nang Lerng is a long-standing community in the Old Town area of Bangkok, an important node of exchange when people arrived more than 100 years ago from many different places and cultural backgrounds. It was originally called Sanam Kwai, meaning “field of buffalo” because there were a lot of buffalo living there when there were only a few houses. Our “Buffalo Field” recalls the history of Nang Lerng, with the original forces of life that created this place, but also the way something is awakening in the spirit of local people and their culture." Buffalo Field Festival, 2019

Nang Loeng is known for its famous food market and as a historic neighborhood on the northern edge of the Bangkok Old Town area. [note 1] Before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was popular with tourists and full of old shophouses and compelling architecture, including Bangkok’s oldest freestanding wooden cinema, Sala Chaloem Thani, and a Buddhist temple, Wat Sunthon Thammathan (Wat Care Nang Loeng). The original community still lives here, although behind the renovated shopfronts and wandering charm of narrow back alleys, the rusted iron cladding indicates the poor living conditions of local people. Despite the continuity of many generations in this place, the urban fabric constitutes an informal settlement typology in dire need of upgrading. Any urgency around this only adds to a deeper uncertainty in the light of gentrification. Nang Loeng, sitting on the fringe of the Old Town—where gentrification has been more gradual—has been cushioned from the juggernaut of urban development to some extent. This will accelerate, however, with a recently approved metro line whose stations, planned at the edge of the community, will bring immediate evictions for some and long-term uncertainty for many others as land speculation skyrockets through improved access to the area.

Nang Loeng has always been a place where art scenes overlap with interdisciplinary and cross-cultural influences. After early settlement by people migrating from the south of Thailand during the reign of King Rama III (1788–1851), the area was transformed with the Phadung Krung Kasem canal built by King Rama V (1868–1910). Rice fields and buffalo gave way to lively merchant trading, and from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century, Nang Loeng was a vibrant cultural hub with famous musicians, music bands, actors, and actresses all gathering in the area.Hundreds of people came to daily movie screenings at the Sala Chaloem Thani Cinema (built in the early 1910s), while in the 1960s, “Mitr Chaibancha, one of the greatest Thai actors of all-time, lived in Nang Loeng until his untimely death” (Yamtree and Castanas 2017, 21). Western-style dancing also had a strong presence in the neighborhood during this time, through a self-taught ballroom dancer—Jadkit Tamornsuwan—who opened a dance school on the first floor of his house. This became a focal point for artists and entertainers from across Bangkok, many of whom were well known at a national level.

After the closure of the school in 1979, followed by decades of disrepair, the “Dancing House,” or “Ban Ten Rum,” was eventually brought back to life as a community space. Between 2012–2014, community architects Openspace led a conservation project in collaboration with local people, using storytelling, participatory design, and cocreation activities to restore the building and revive its cultural memory. Working closely with E-Lerng, an art collective based in Nang Loeng, the conservation project was at the same time intended to “renovate” community cohesion as a process of sustainable placemaking (Yamtree and Castanas 2017, 27). [note 2] The E-Lerng collective has run many art projects and festival events with residents over the years while hosting visiting artists and conserving local traditions, such as the Lakhon Chatri form of song and dance. They see how art and culture provide tools for community engagement, development, and collective mobilization, especially where issues of poverty and marginality may offer new expression for activism and advocacy and creative techniques for sustainable living.

Of Buffalo

Buffalo Field Festival came about in the light of these shifting borders—tangible and intangible, historical and contemporary, collaborative, communal, precious, precarious. In 2017, a small group of us—a mix of “insiders and outsiders”—put together “Embodied Movement,” an evening of performance in the outdoor areas around the temple, with two dance workshops in the lead-up to the event. Ploy Yamtree, from Openspace, had introduced me to community leader Dang Suwan Welployngam and her daughter Nammon. Together, we discussed the potential for a community-based festival that might respond to the unique urban fabric of Nang Loeng through site-specific performance, in parallel with socially engaged and participatory art practices, in ways that complement the community development and codesign approaches that were already underway.

I invited three long-standing collaborators to perform and advise—Tony Yap (Malaysia/Australia), Agung Gunawan (Indonesia), and Takashi Takiguchi (Japan)—as an initial test, to see how it would be received by the community and to explore creative possibilities. The following year, Buffalo Field was born, with twelve international artists from seven countries performing over two nights outside the old Sala Chaloem Thani Cinema and at various spots around the temple area. There were several dance workshops as well as a short daytime program, with continuous performances over the space of an hour through the interior and rooftop of an old, abandoned clinic, which local leaders were trying to secure as a venue for a community center.

For Buffalo Field 2019, we added a “Local Studio” component to the program, an intensive community consultation and participation process based in the Dancing House in the two weeks leading up to the festival. The studio began with a community forum, a big sharing session attended by residents who are actively engaged in the life of Nang Loeng, which also drew leaders from other communities and local government officials from the district office. From our early conversations with P’Dang and Nammon, [note 3] we had decided on three themes for the studio and festival: Sustenance, Settlement, and Social fabric. This sought to encapsulate some of the main concerns in the neighborhood, such as poverty and rapid development, traditional livelihood and hospitality, food security, and insecure land tenure.

What followed was a series of workshops and ongoing discussions, with a working group for each theme that included members of the community, public participants, and a small group of local and international academics, some of whom traveled especially for the event. Thematically focused conversations served to explore the issues in more detail, finding new approaches to tricky subjects, in parallel with creative techniques in art, design, and performance. Physical and conceptual prototypes appeared in pop-up events around the streets, alleyways, and shophouses, offering inventive ways to collect data and gather stories while raising awareness in the neighborhood and priming the festival to come.

With the arrival of international artists five days before the festival, a studio debrief was held back at the Dancing House to give studio participants a chance to reflect on the whole process. This was an important handover and a handshake for community members to welcome the artists through the gift of these activities and an invitation to cocreate. The studio set the scene for the festival, giving the artists a broader context for their own site-specific performances as well as a range of material resources and local networks. The community response was phenomenal throughout the process of Local Studio and Buffalo Field—not just in the workshops and discussions but also in collaborating with artists, offering stories and songs, opening their shops as site-specific venues, performing in day and night programs, and jamming together in improvised actions around the streets.

That was then, this is now. Buffalo Field 2019 happened just a few months before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the 2020 infection rates were relatively low in global terms across Thailand, marginalized communities in informal settings like Nang Loeng were affected far more severely, especially with the arrival of the Delta variant in 2021. Government shutdowns also had a significant impact on livelihood and food security, alleviated to some extent through food drops by NGOs. The local spike in infections brought the loss, sadly, of several people in the Nang Loeng community, including some of those we came to know through Buffalo Field.

Our decision to postpone the festival was due not just to the reality of COVID-19 but also to a need to reflect on our capacity as a community/artist/activist–run initiative and on some of the questions that always haunt social practice. What is the value in using art and design for community development? What potentials and limitations lie on each side—for artists, activists, and local residents? In a recent Zoom interview with P’Dang and Nammon, they reiterated how Local Studio and Buffalo Field helped to “reawaken” something in the spirit of local people. Over two years later, and still in the midst of a pandemic, we wonder what this might hold for the future, in all its uncertainty.

This contribution to Techniques Journal gives us an opportunity to reexamine these protracted borders: back then, where we are now, and what happens next. At the time of writing, we’re completing a short video documentary on Buffalo Field, which also helps to clarify the process. [note 4] What follows here is a photo essay of sorts—“Notes from the Field”—where we explore in more depth some of the contexts, themes, and features of Buffalo Field. Particularly, how may these be understood by their edges and thresholds, in the strange bordering conditions that exist within and between the formal and the informal, community, ritual, performance, sustenance, settlement, and social fabric?

To borrow a phrase from another Openspace project on community participation (Castanas et al. 2016), what could it mean to “Leave no one behind” in the context of Buffalo Field—especially where the borders of “community” are forever shifting, contested and porous, protracted and unstable, and include insiders and outsiders? The principles of cocreation offer a few tips, where we find “expertise” embedded in every participant, where “inclusion” acknowledges those parts of ourselves that may have been delayed—or need a collective approach to self-care in order to come forward. We are all here in this moment—let’s share, listen, do something together, even if we don’t know what it is exactly, where to start, or how to continue . . .

Notes from the Field

Formal and informal processes are not always clear and distinct, especially where built and social fabrics interweave as a mutual expression of lived experience and everyday environment. Informal settlements are often thought of as improvised, nonlinear assemblages, the density and variation of which somehow reflecting the loose, ad hoc dynamism of their social relations. But the marginal existence of these communities, on the edge of society in many ways, cannot be understood without the formal overlays of urban governance and development or the in/formal protocols that local leaders and advocates use to protect local people. As outsiders working with communities, we need to be aware of the fragile constraints and vulnerabilities unique to their situation and that there is, too often, a history of misplaced intentions from people like us. So just as we find unexpected areas of expertise in the way local people live with marginality, we also learn to reflect on what (we think) we have to offer.

The forum that kicked off Local Studio showed how community representation and advocacy is so layered and multifaceted, a weaving of horizontal and vertical relations encompassing both residents, from elders to young families, and leaders, from the district level to neighboring communities and those living in the immediate area. And various outsiders, including those of us who have worked in Nang Loeng for a while, some new to the process, and many who come sharing other communities of practice (academics, architects, designers, performers).

In Nang Loeng, there’s an openness to the way outsiders bring new creative perspectives. For Buffalo Field, this was evident from the very first performance in 2017, when Benjamin Allen pulled Takashi Takiguchi out of the gloom on an old cart they’d borrowed from the temple. P’Dang described how the audience, a small group of mainly local residents packed into a narrow wedge shape tucked away behind the temple buildings—an area that had always felt a bit scary as they grew up—was fascinated by the way an object they used every day was transformed through Takashi’s playful evocation of the dead.

If outsiders can be seen to configure horizontal and vertical relations in new ways—a transverse bordering, if you like—this can destabilize as much as invigorate community, especially when they bring to the inside those things that already haunt its fragility. We see this at the macro scale in gentrification, where creative organizations working with community (ourselves included) find things worthy of celebration and development while becoming indirectly complicit in the commercial speculation that shadows cultural revitalization.

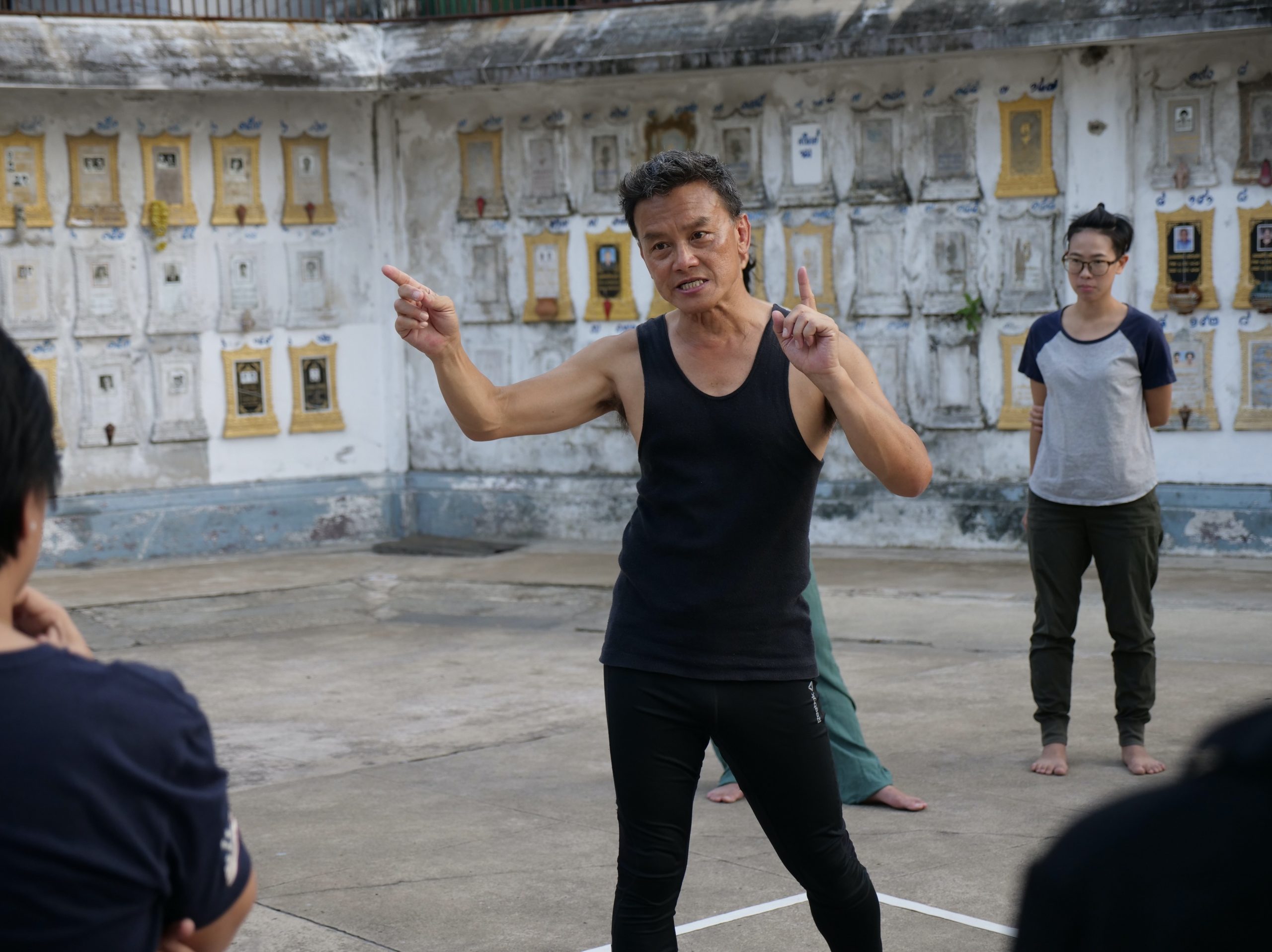

At Buffalo Field, this fragility is felt in a more immediate way. It comes with an enormous trust to perform in spaces that are deeply personal or profoundly sacred—such as the columbarium wall in the temple area where the ashes and portraits of past generations are kept, or with our shophouse collaborators in their workplaces of traditional livelihood, or gatherings on the main street and semiprivate back alleys, or at the heart of local history and public life, in the open space in front of the Sala Chaloem Thani Cinema.

The significance of ritual is embedded in the life of communities like Nang Loeng, with the Buddhist temple at the center, household shrines throughout the neighborhood, and local customs full of everyday ceremony, both formal and informal. If we can say that a people are always “yet to come” (Deleuze 2003), as a process of becoming and fabulation, we may also see how a community realizes itself with each gathering—and in sustaining its potential for the future, there are also those who came before, still felt here as a community of spirits.

In Thai tradition, there’s a strong belief in the coexistence of family ancestors as a profound presence through which local people carry the continuity of generations in one place, shared through stories and a deep knowledge of the surrounding environment. There’s also an animist underpinning to everything, a belief that all things have (a) spirit. This brings another quality to the sense of place—singularly embodied and seemingly infinite, or at least vague in outline and vitality—in the way a house, a tree, an artifact . . . lives with us.

P’Dang and Nammon describe how ritual plays an important role in welcoming outsiders, bringing insiders and outsiders together. Following the forum at Local Studio, a group of community elders walked to the temple to say a prayer together, to ask a blessing for the coming event. At the end of the studio debrief, community leaders and elders took all the artists and studio participants along to do the same thing, an experience that was both sincere and straightforward, putting aside differences in belief or abstract nods to cross-cultural understanding. It was a perfect welcome, as the Dancing House then became the festival base, hosted by the ghosts of dancers, where the artists prepared and rehearsed, had meals together, and from there explored the community to develop their work.

For artists working in site-specific performance and social practice, aspects of ritual are often inherent to their craft and can offer important bordering techniques for engaging with local audiences and collaborators. At the start, there’s immersion in an unfamiliar (and oftentimes foreign) environment, as this comes together through scoping the neighborhood, meeting local advocates, and understanding how social contexts are situated through the built fabric, objects, and other materials. All this arrives in a specific time and place, at a site imbued with local significance, even as the act of performance serves to shift meaning into more abstract and affective areas. In performance, clear interpretations often elude capture or proliferate in our minds as the mere outline of an idea, as performers seem to trace an atmosphere of unlimited possibilities, both tangible and ghostly.

As in Takashi’s opening piece with the old cart from the temple, there are many examples where performers use locally sourced objects and materials—everyday things becoming conceptual apparatuses and affective intercessors, bordering on the familiar and the uncanny. Kathleen Gonzalez emerging out of a big rainwater jar in front of the old cinema, Cloudbeard sprinkling rice through the old, abandoned clinic, Alan Schacher wafting sheets of Chinese rice paper in the air. The list goes on . . .

With or without props, artists have different approaches to site-specific performance and social practice, although there are common threads and shared backgrounds at Buffalo Field. Many dancers draw on what are often called psychophysical or “pre-expressive” performance techniques. These focus on an embodied, situated attention to the ways in which the autonomic systems of the body—breathing, sensation, muscle contraction and release—can augment, disrupt, or withhold their impulses, so the emotional qualities that appear through gesture and movement may be seen to become more “authentic.” [note 5]

Proximity is important—firstly, for the performer, as a situated relation to their own intention, vis-à-vis attention, impulse, and expression, shifting back and forth from the inside to the outside. And by extension, the creation of a pervasive mood that potentiates an affective disposition in the audience. The fourth wall is a strange thing in site-specific contexts. You are already in their space, and as you invite them to enter states of alterity and becoming, time and distance seem to dilate or contract. The ephemeral and the eternal rub shoulders for a moment.

From slow preludes that build suspense to climactic flurries of movement and a whole series of thresholds in between, states of vitality are carefully crafted, attending to a continuous flow of spontaneity. Whether choreographed or improvised, every small act of the body harbors a pure reserve of potential, every gesture like the bifurcation of infinite possibilities. In proximity, the audience can feel every flinch of the dancer, as if fused with their own expectation, where a singular gesture or a fictionalized object carries with it their own imagination of diverging associations. Emotional expressions may then be full of affect and empty all at once, held in a nascent state between dancer and audience—whether there’s a sense of anguish and pain or joy, humor, and play.

For artists from cultural backgrounds that are steeped in mythology, the border regions of embodied and collective affects are often where dance techniques enter rich cosmologies of the more-than-human kind. Indonesian shaman Agus Riyanto brings a special presence to Buffalo Field, where many dancers share a deep connection, having been guided by him at festivals in Indonesia and Malaysia over the past decade or so. His actions and materials are somewhat familiar to the local Thai audience in the way he uses ritual to create sacred space, clearing and invoking otherworldly intensities with wisps of burning incense, dipping flowers, and sprinkling water. The sudden crack of his bull whip is something new altogether, while it also conjures a sense of the buffalo spirit. One of the key figures in the Bantengan movement in Javanese shamanic mediumship, Mas Agus invokes the animist spirit of the bull, symbolizing strength of community. [note 6] He embodies a gentle power for guiding performers through liminal states of trance, where magical or uncanny qualities seem to fray at the fringe of psychophysical affects. [note 7]

While proximity and affect may open the fourth wall to collective inclusion, the subtleties of psychophysical performance (and trance work especially) tend to, by nature, remain on the side of the unsaid and the inexplicable. Through the dance workshops, facilitated by artists as part of the festival program, local participants could experience this area for themselves, learning some of the techniques and surrounding cultural contexts to gain a deeper appreciation of the performances. In 2019, Agus Riyanto and Tony Yap held what they called a Contemplative Trance Workshop, exploring the sensitive relationship between internal and external states of awareness. Moving between subtle planes of perception and feeling, participants experienced how their surroundings and emotional states can alter by shifting focus inward and outward.

Agung Gunawan explored kindred terrain in his own workshop for 2019, taking participants into the borderlands of sensation and metaphor: breathing—wind giving breath; listening—wind whispering to the ear; sensing—wind touching your skin; floating—wind rocking you like a cradle. With his understanding of the traditional Srimpi dance form in Indonesia, Mas Agung guided an experience into the four requirements for perfecting the art of Javanese court dance: sawiji—concentration of mind; greget—enthusiasm and consciousness; sengguh—self-confidence; and ora mingkuh—no surrender. With many participants having little or no dance background, these psychophysical techniques, often framed through devotional traditions of various kinds, offer a different virtuosity, an authenticity grounded in their own situated attention and embodied imagination.

Another key area of performance in the festival is socially engaged art, with performance artists and codesigners utilizing participatory, inclusive, and relational approaches. WeiZen Ho’s “Social Walking Ritual” set the tone in 2018, with a walk through the neighborhood from the old clinic to the old cinema connecting daytime and evening sites in the program. Local elders and children led artists and festival participants through the streets and lesser-known back alleys, leaving behind a trail of yellow flowers as a collective ritual—a reflection on community well-being and a symbolic reclaiming of the ground upon which the walk took place. Socially engaged actions and performances really came into their own in 2019 through workshops and pop-up events as part of Local Studio and the influence they had on the festival program. (See further below, Themes 1, 2, 3—Sustenance | Settlement | Social fabric.)

The bordering of proximity and affect varies for different approaches to social practice. In psychophysical performance, the dancer cultivates an internal threshold of thinking-feeling as a pre-expressive relation with others. Affective shifts connect performers and audience on either side—the fourth wall held in place, albeit tentatively, through fluctuations of inside and outside, between embodied and situated attention. By contrast, in performance art, the artist is often “just themselves,” not acting per se but rather acting through real materials, actions, and artifacts, where affects shift via duration, endurance, abjection, and so on. A different distance occurs when situations coexist “on the same plane as those that witness it”—on a human scale, in real time and place (Marilyn Arsem, in Klein and Loveless 2020, 2). There are of course many crossovers for approaches such as these, and boundary conditions shift again when community members participate or collaborate with the artist to whatever extent.

When Japanese artist Kiki Ando performed with local barber Bunmee Rodjaroon, she flipped the script by cutting his hair in his own chair. A costume designer, performance artist, and hairdresser, Kiki reassured him that she was “a professional,” and he was delighted to switch places in a way that recognized his role as the last traditional barber in the community (Kongthong 2020). The audience gathered tightly together on the sidewalk to peer through the shophouse entrance, framing the intimacy of the encounter with the social dimension of a shared expertise.

On the opposite side of the street, a little further down, Stephen Loo performed a culinary sound action with Gandhi Wasuvitchayagit and Annmanee Singhanart, accompanied by local butcher Wannee Lertudommongkol and two street-side chefs, Orrapan Thanun and Yaowarat Thanun. A meat cleaver thuds on a wooden block with a contact microphone attached to the blade as a large portion of pork is cut to resound across the street, where the audience stands opposite. A sonic act of slowing time—between eating, listening, and thinking—and in the preparation of both the food and the work, which evolved through a series of collaborations and meanderings, including an old folk song by a ninety-year-old grandmother best known for her foot-tickling as a cure for insomnia (See Loo 2022, forthcoming; also below, “Theme 3—Social Fabric”).

With the barber and the butcher, it is the placemaking around specific sites, the neighboring connections, and collaborators’ social relations that perform a broader process, as much as the actions of the artists themselves. Day-to-day activities that occur in that very place become timeless for a moment—or indeed untimely, in the act of performance; at once altered, ephemeral, and eternal in the cultural memory of those that witness it.

Whether it’s psychophysical dance, participatory social practice, or somewhere in between, site-specific performance in these contexts requires a lot of coordination. More than just gaining permission, a sensitive back-and-forth unfolds in supporting what artists need to transform the space and how the experience of community members can be enhanced or celebrated without stepping on any toes in the process. The Openspace team and community organizers worked tirelessly to make it all happen, and as the artists, residents, and visitors became audience, performers, or participants in various ways, a microcommunity of sorts formed through the singular eventfulness of the festival.

Bangkok-based Thai artists and academics made a valuable contribution to the 2019 program. With most of the international artists arriving just in time for the studio debrief to focus on the festival week to follow and international academics partway through the studio at various points, this Bangkok-based presence early on allowed a crucial segue for insiders and outsiders. There’s an ease that comes with shared language and sensibility, especially for those familiar with socially engaged practice on the ground, and this really helped to build momentum, cohesion, and anticipation for the coming community from overseas. [note 8]

Finally, if we can see how this reveals a nuanced layering of agency and disposition, as events gather potential, it is in the most intimate of local relations where the subtle powers of affect may be felt most pervasively. In the first iteration in 2017, we opened with a performance by a young martial arts group from a neighboring community, but it wasn’t until 2019 that so many local strands came together at different scales and relations—not just through community organizing and participation but also at the level of family and support for emerging artists.

This was especially powerful in both the curation of local experts by Nammon Welployngam and her team and in the opening Lakhon Chatri dance performance featuring her younger sister, Namo Welployngam. As Namo said in an interview with the Association of Siamese Architects in their “Co-Create” issue (Kongthong 2020), she felt nervous performing alongside established international artists but was also proud to share the traditional Lakhon Chatri dance in one of its last surviving communities of practice. Beyond the ornate costume and subtle precision of Namo’s gestures, an affective intensity held the space as her mother, P’Dang, marked each movement with a steady tok-tok-tok of wooden sticks to the haunting voice of Lakhon Chatri master performer Kanya Thipyosot.

Lakhon Chatri is a traditional form that’s threatened in many ways by the incessant pace of modern society, as are many of the communities that practice it—both recalling a time when close family and social gathering naturally coalesce in places like Nang Loeng.

The edges of other worlds enter momentarily as the rest of the evening program unfolds in this sacred space behind the local temple, where the portraits and ashes of local ancestors line the walls. At Buffalo Field, there’s a sense of converging realms, a bordering of intimate relations at once far flung and closer still, through transformations of proximity and place.

Theme 1: Sustenance

~ food security, urban farming, upcycling, hospitality . . .

While it is home to one of Bangkok’s most famous markets and is well known for its specialties, many residents in Nang Loeng struggle to afford or access good-quality food, often depending on food donations from the local temple. [note 9] Urban farming allows people to become more self-sufficient and offers useful methods for marginalized communities. In Local Studio, we explored ideas around food security, hospitality, and upcycling food waste to prototype several pop-up propositions as a way of raising awareness around the neighborhood. Led by Ploy Yamtree, the Sustenance group focused on three activities: mapping edible garden corners within the community, making a garden bed using discarded soda bottles, and creating a mobile edible garden from used wine bottles mounted on an old cart trolley.

When mapping edible garden corners around the community, we asked people, “What do you want to grow, and why?” The most common reasons for growing plants were for good fortune, appreciation, and beautification, for cooking meals, and for using them as medicine. We chose a site donated by a local resident to create our garden bed prototype. This used discarded elements, making it fully upcycled—empty soda bottles for the sides, bamboo pieces from a construction site to make the frame, old tire strips for tying it together, and old t-shirts to make the bed. While the garden bed is at the front of the house, the owner also wants it to be a communal space, with everyone invited to help take care of the plants.

The mobile edible garden used an old cart as a moving ideas space for asking community members two questions: “What would you like to grow if there were a community garden space on a cart like this?” And, “What is food security in Nang Loeng?” We took the cart around the community and got input from as many people as we could. They wrote their answers on paper flags, as a collective blueprint for what sustenance might look and taste like. These interventions highlighted some cheap and easy responses to food insecurity in places like Nang Loeng. Price and availability of space are often deterrents for gardening, and so we sought to emphasize that they are not necessarily restrictions.

Thai percussionist Annmanee Singhanart collaborated throughout the process, bringing a musical dimension to the mobile edible garden cart—jamming with us in the Dancing House, the street interventions, and in both day and evening programs, where the cart became a feature. Another crossover for the Sustenance and Social fabric themes was the welcome dinner on the evening before the festival opening night, where several street vendors became our “community chefs” for a long-table dinner on the sidewalk of Phaniang Road (the main street delineating the temple and market sides of the community).

Theme 2: Settlement

~ gentrification, insecure tenure, upgrading, restoration . . .

As with many informal settlements in Bangkok, the inhabitants of Nang Loeng live with the looming threat of eviction as the city grows and often develops without them. The community has a distinct local color, but one that is vulnerable to gentrification. As noted above, the new subway line will displace many. Land tenure is insecure for most households, with families renting on an annual basis from the Crown Property Bureau. In stark contrast to the impact of urban infrastructure, there’s the need to upgrade poor living conditions while retaining the character of the neighborhood with heritage restoration or adaptive reuse projects. However, restrictions on house alterations limit DIY solutions and design-build interventions, while the difficulties of finding community consensus sometimes hampers policy change in land tenure for the benefit of local residents.

Led by Yoswadee Sonthichai and myself, the group explored settlement through game design. Games are a useful approach in creating horizontal discussions on sensitive topics, offering a nonthreatening space for people to share their issues and dreams with outsiders. Our “Settlement Game” is based on a process developed by Ceridwen Owen, Kim Dovey, and Wiryono Raharjo, originally used to understand informal settlement dynamics within kampung (village) communities in Yogyakarta, Indonesia (Owen et al. 2013). Adapting this to Nang Loeng, the group started by mapping important spots in the community—as they are now, as well as 50, 100, and 150 years ago. A lot of stories came out as people shared ways of decoding the community’s history by devising the rules of the game, deciding what threats the community faced, and creating “challenge cards” to represent these.

We also created “dream cards” to reflect the types of spaces people wanted to see in the community. About six months before Buffalo Field 2019, E-Lerng and Openspace narrowly missed out on securing an old, abandoned clinic in the neighborhood, with the dream of turning it into a community center. [note 10] In 2018, we had performed throughout the building, from the ground floor to the rooftop, exploring qualities of abandon, dis-ease, cleansing, and clearing. Having conjured its ghosts, we wanted to preserve what we could. Polish-Australian artist AñA Wojak had performed a simple ritual in the 2018 daytime program by washing a large collection of old medical bottles that had been left behind in the clinic, and these became a new feature for the local Arts House archive.

In Local Studio 2019, the Settlement group carried the collection around the community on a cart trolley (like the mobile edible garden in Sustenance). The bottles tinkled together as the cart rattled along, and we invited local people to make sounds with them as Thai artist Gandhi Wasuvitchayagit sampled, looped, and reprocessed the audio on a second cart, playing it back live as the procession moved around the streets.

Recalling the story of the clinic, we asked people, “What do you think we need to take care of in the community, and what needs to be healed?” People wrote down their answers, and these became new labels for the bottles they chose. On the day before the festival opened, we did a “playtest” on Phaniang Road, an all-ages game improvisation that made up the rules as it went along—spinning the bottles to choose challenge and dream cards, telling stories, and cracking jokes. The bottles went on to find a place in the evening performance program, with me dancing as a mad doctor, accompanied by Gandhi and Annmanee on percussion and electronics, as local audience members and artists carried the bottles into the space one by one.

Theme 3: Social Fabric

~ livelihood, cultural memory, local expertise . . .

The cultural memory of life in Nang Loeng is often felt in places of traditional livelihood, where shophouse traders, market stallholders, and street vendors create valuable nodes of exchange between the built and social fabric across the community. Led by Nang Loeng artist and community organizer Nammon Welployngam, the Social fabric group worked with participants to map areas of local expertise. The group recognized that people are the experts of their own community, even when local knowledge, heritage, and culture are looked down upon as lacking value in a rapidly changing urban context. Flipping the narrative, we looked for “local experts” within Nang Loeng to highlight their craft and the important role they play in the community.

Five local experts were chosen along Phaniang Road—a tailor, a barber, a butcher, a luggage repair man, and a bicycle shop owner. All agreed to open their places of vocation for collaboration with festival artists and audiences. Photographic studies and design drawings were made to document work interiors and activities, while an exchange of gifts made for an intimate transaction that acknowledged the collaboration to come. Each expert received a portrait of themselves drawn by local artist TariPalm, while they offered tools of their trade as symbolic props—a set of knives, an old sewing machine, a pair of scissors and a comb, a set of suitcase trolley wheels, and a bicycle cog. Meeting the local experts was an important welcoming ritual for all the artists as part of their orientation within the community. Six artists chose to collaborate, with a series of follow-up sessions to plan each performance as part of the festival day program.

On the day, the audience moved down the street from one performance to the next. Malaysian/Australian artist Tony Yap starts off, rolling around on a shophouse floor with bits of off-cut fabric as two local tailors go about their daily tasks around him. Evoking memories of childhood, with the safety and innocence of playing on the floor while his mother and her friends sewed garments, he emerges from the interior to dance at the entrance, exploring an empathetic openness with the audience gathered closely around on the sidewalk.

We move down the street, following Annmanee and local participants pushing the mobile edible garden cart from the Sustenance group, carried along by the percussive tinkling of upcycled wine bottles. The crowd stops at the barber for a haircut with Kiki and Bunmee, then crosses the street to where Annmanee plays alongside Stephen Loo and Gandhi Wasuvitchayagit with the local butcher (see details above, in “Notes from the Field”).

I’m seen coming down the street like some weird animal-spirit transformation of tourist and turtle, crawling on all fours with a suitcase strapped to my back with bicycle inner tubes (from the luggage and bicycle repair shops). Stephen steps out with a surprise maneuver, placing a plate of pork on the street in front of me. I devour it voraciously but then fling the plate skittling down the street as the chili burns my face. Writhing and dragging my luggage body along, I stop to hail a local motorcycle taxi, which picks me up, suitcase and all, to disappear around the corner into the temple area. The audience moves on down the street as the mobile edible garden cart arrives at the bicycle repair shop. Malaysian artist Kien Faye emerges from the interior to the longing tune of an old Chinese song. With comedic nostalgia, he takes on the female persona of a shophouse spirit, imploring his materials—tires and spanners and inner tubes—to return his long-departed children.

From close encounters in shophouses to street actions and alleyway meandering to the main evening venues behind the temple or in front of the old cinema, sites and situations serve to enact the genius loci or spirit of the place, full of histories and fictions, against the backdrop of an ever-changing community.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We’d like to extend a heartfelt thanks to all the Buffalo Field Festival artists, Local Studio participants and cofacilitators, Openspace team, and Nang Loeng leaders, community participants, shop owners, and house owners who offered their space and enthusiasm. As an artist-activist run initiative, Buffalo Field relied on the generosity of international artists to support their own travel, stay, and materials, and local advocates to welcome and work with them. We’d also like to thank the Center for Philosophical Technologies for contributing to logistics for the 2019 program and all the academics who joined us at Local Studio and the festival: Adam Nocek from Arizona State University, Wijitbusaba Ann Marome and Boonanan Pan Natakun from Thammasat University, Stephen Loo from the University of New South Wales, and Julian Worrall from the University of Tasmania.

REFERENCES

- Castanas, Nausica, Ploy Yamtree, Yoswadee Sonthichai, and Quentin Batreau. 2016. “Leave No One Behind: Community-Driven Urban Development in Thailand.” (working paper, International Institute for Environment and Development, London). https://pubs.iied.org/16629iied.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 2003. Cinema 2: The Time Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Klein, Jennie, and Natalie Loveless, eds. 2020. Responding to Site: The Performance Work of Marilyn Arsem. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Kongthong, Parawit. 2020. “Buffalo Field Festival.” ASA CREW 9 (Co-Create): 136–141.

- Loo, Stephen. 2022 (forthcoming). “On the Political Biology of Eating and Performing (with) Food.” Performance Research 26, no. 8 (On Biopolitics).

- Owen, Ceridwen, Kim Dovey, and Wiryono Raharjo. 2013. “Teaching Informal Urbanism: Simulating Informal Settlement Practices in the Design Studio.” Journal of Architectural Education 67, no. 2: 214–223.

- Yamtree, Ploy, and Nausica Castanas. 2017. “Community at the Heart of Cultural Heritage Management.” In Grounded Planning: People-Centred Strategies for City Upgrading in Thailand and the Philippines, edited by Catalina Ortiz and Barbara Lipietz, 19–32. Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London.

BIOGRAPHIES

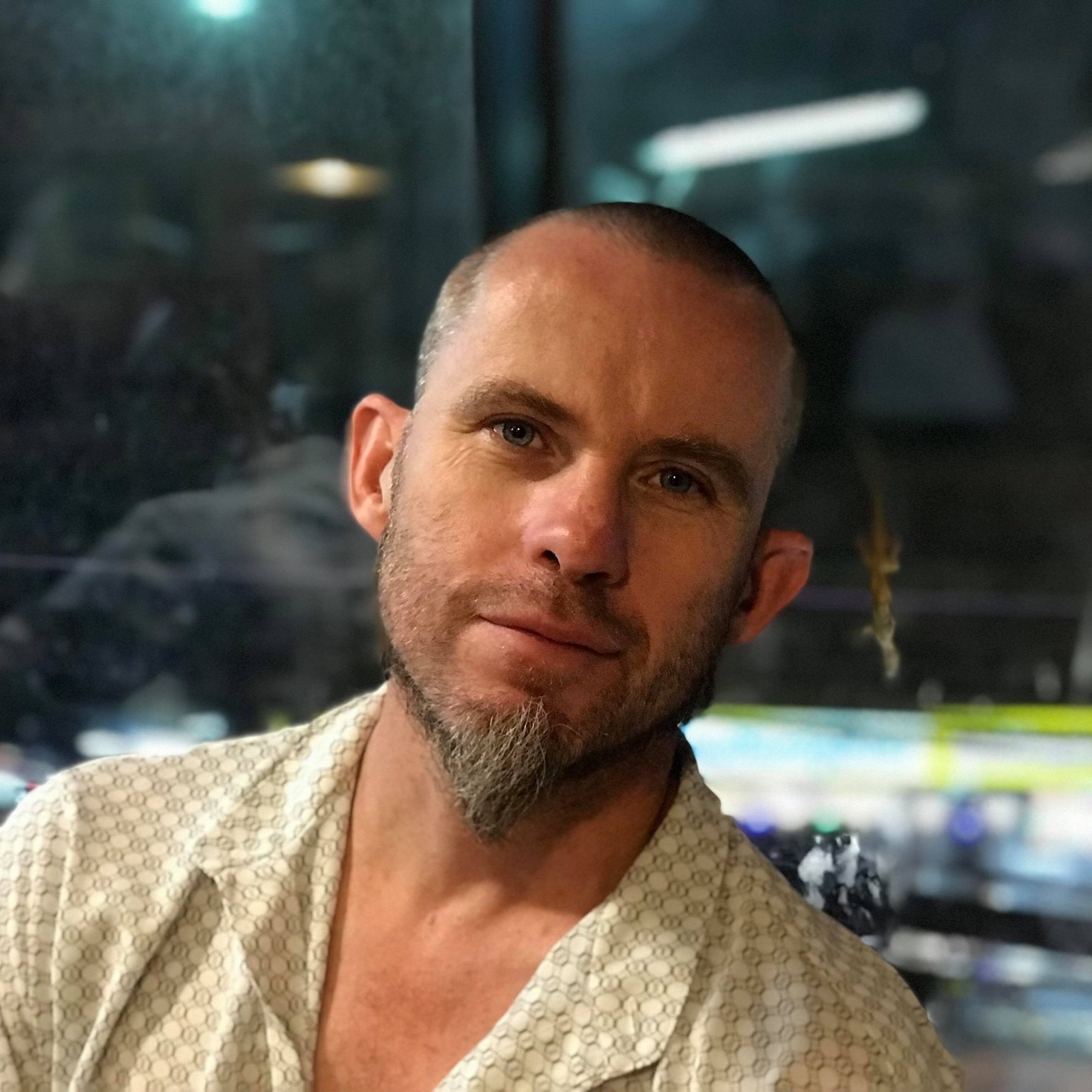

Michael Hornblow

Michael Hornblow (he/him/his) is an interdisciplinary artist, researcher, and creative director based in Bangkok, where he is a Lecturer at Thammasat University. Michael has a broad creative background across video, public art, performance, and design, including presentations at Melbourne Festival and the International Symposium on Electronic Art (Sydney, Vancouver, and Hong Kong). He has a long history of creative work in Asia, including art residencies with Asialink and the Australia Indonesia Institute, and festivals in Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan, and Thailand, including artistic directing and cofounding Buffalo Field in Bangkok.

Michael Hornblow (he/him/his) is an interdisciplinary artist, researcher, and creative director based in Bangkok, where he is a Lecturer at Thammasat University. Michael has a broad creative background across video, public art, performance, and design, including presentations at Melbourne Festival and the International Symposium on Electronic Art (Sydney, Vancouver, and Hong Kong). He has a long history of creative work in Asia, including art residencies with Asialink and the Australia Indonesia Institute, and festivals in Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan, and Thailand, including artistic directing and cofounding Buffalo Field in Bangkok.

Ploy Yamtree

Ploy Kasama Yamtree (she/her/hers) is a community architect based in Bangkok, working in the areas of knowledge management, community architecture, and development. She uses co-design processes involving design, art, architecture, planning, communication, environment, public health, food security, and climate change. Kasama is Senior Architect and Director of Openspace, an open ground for interdisciplinary collaborations in community development, and Tar Saeng Studio, which aims to promote Universal Design knowledge and adaptation across Thailand. In addition to her work at Openspace, Kasama has coordinated projects at the regional level through her work with the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights and Community Organizations Development Institute.

Ploy Kasama Yamtree (she/her/hers) is a community architect based in Bangkok, working in the areas of knowledge management, community architecture, and development. She uses co-design processes involving design, art, architecture, planning, communication, environment, public health, food security, and climate change. Kasama is Senior Architect and Director of Openspace, an open ground for interdisciplinary collaborations in community development, and Tar Saeng Studio, which aims to promote Universal Design knowledge and adaptation across Thailand. In addition to her work at Openspace, Kasama has coordinated projects at the regional level through her work with the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights and Community Organizations Development Institute.

Nausica Castanas

Nausica Castanas (she/her/hers) is a photographer, social researcher, and digital content creator based in London. Her work has taken her around the world—from Ghana to Malaysia and Thailand. She has extensive experience working with urban communities, most recently through her work with Openspace—a community architecture studio in Bangkok—and the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights. Her research focuses on the right to the city, participatory community planning, climate change, and sustainable adaptation practices.

Nausica Castanas (she/her/hers) is a photographer, social researcher, and digital content creator based in London. Her work has taken her around the world—from Ghana to Malaysia and Thailand. She has extensive experience working with urban communities, most recently through her work with Openspace—a community architecture studio in Bangkok—and the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights. Her research focuses on the right to the city, participatory community planning, climate change, and sustainable adaptation practices.

NOTES

1. The modern transliteration for the area is “Nang Loeng,” while for the 2019 promotional material, we used its traditional spelling, “Nang Lerng.”

2. See also Francesco Pasta for further discussion of the Dancing House and the community architecture of Openspace (“Reflecting on the Practice of Community Architects: The Case of Nangloeng,” in Bangkok: On Transformation and Urbanism, edited by Giovanna Astolfo and Camillo Boano, 88–101. Bartlett Development Planning Unit: University College London, 2016).

3. In Thailand, P’ is used as a title for someone older, as a sign of respect and familiarity. It literally means “elder sibling” but can be used for anyone older than the speaker/writer.

4. See weblinks for updates on forthcoming video works and other events: michaelhornblow.com/buffalo-field; openspacebkk.com/buffalo-field-2019.

5. See Michael Hornblow, “Sponging the Chair: Diagramming Affect through Architecture and Performance” (PhD diss., Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, 2013), for a discussion on the problem of authenticity in psychophysical performance practice, in relation to situated and embodied cognition, as a process of becoming rather than appearance.

6. In Indonesia, Mas is an honorific title used to address older men. Literally meaning “bro”/“brother,” it comes from the Javanese language but is widely used across Indonesia.

7. See Hornblow (2013) for an analysis of psychophysical performance through discussion of the “fringe horizon” in Francesco Varela’s “The Specious Present: A Neurophenomenology of Time Consciousness” (in NaturalizingPhenomenology: Issues in Contemporary Phenomenology and Cognitive Science, edited by Jean Petitot et al., 2000). See also Tony Yap, “Trance-Forming Dance: The Practice of Trance from Traditional Communities to Contemporary Dance” (PhD diss., University of Melbourne, forthcoming) for a discussion of trance practice in dance, with a focus on Agus Riyanto and the Javanese Bantengan movement.

8. Our Local Studio collaborators Wijitbusaba Ann Marome and Boonanan Pan Natakun, from Thammasat University, have also worked previously in Nang Loeng on a range of projects, some in collaboration with Openspace. See Boonanan Natakun and Non Arkaraprasertkul’s “‘Updated Sense of Belonging’ of Nang Loeng” in the Southeast Asian Neighbourhood Network (SEANNET) Blog.

9. The “Themes” section (1–3) has been developed with reference to the Buffalo Field write-up on the Openspace website (Nausica Castanas and Ploy Yamtree, “Buffalo Field 2019: Workshops and Performances in Nang Lerng”) and the Local Studio Call for Participation.

10. Dr. Uthai’s clinic had been vacant for more than a decade; it is ideally placed, at the front of the alley going down to the Dancing House, with the community Arts House halfway down on the opposite side.