Pulp Fiction

One often assumes a gulf between nature and culture. Such dichotomies abound in the West. Yet, there is a dark connection that links together the organic infrastructure of nature and the mass-produced infrastructures of capitalist societies. Here, infrastructure does not merely concern built environments for human habitation but also includes grown environments—a thicket of material latices, budding biological networks, and organismic gestures that all support life. Infrastructural relay points underlie what Timothy Morton refers to as the “strange loop” (2016, 7) that defines dark ecology, in which nature and culture twist around one another, becoming indistinguishable.

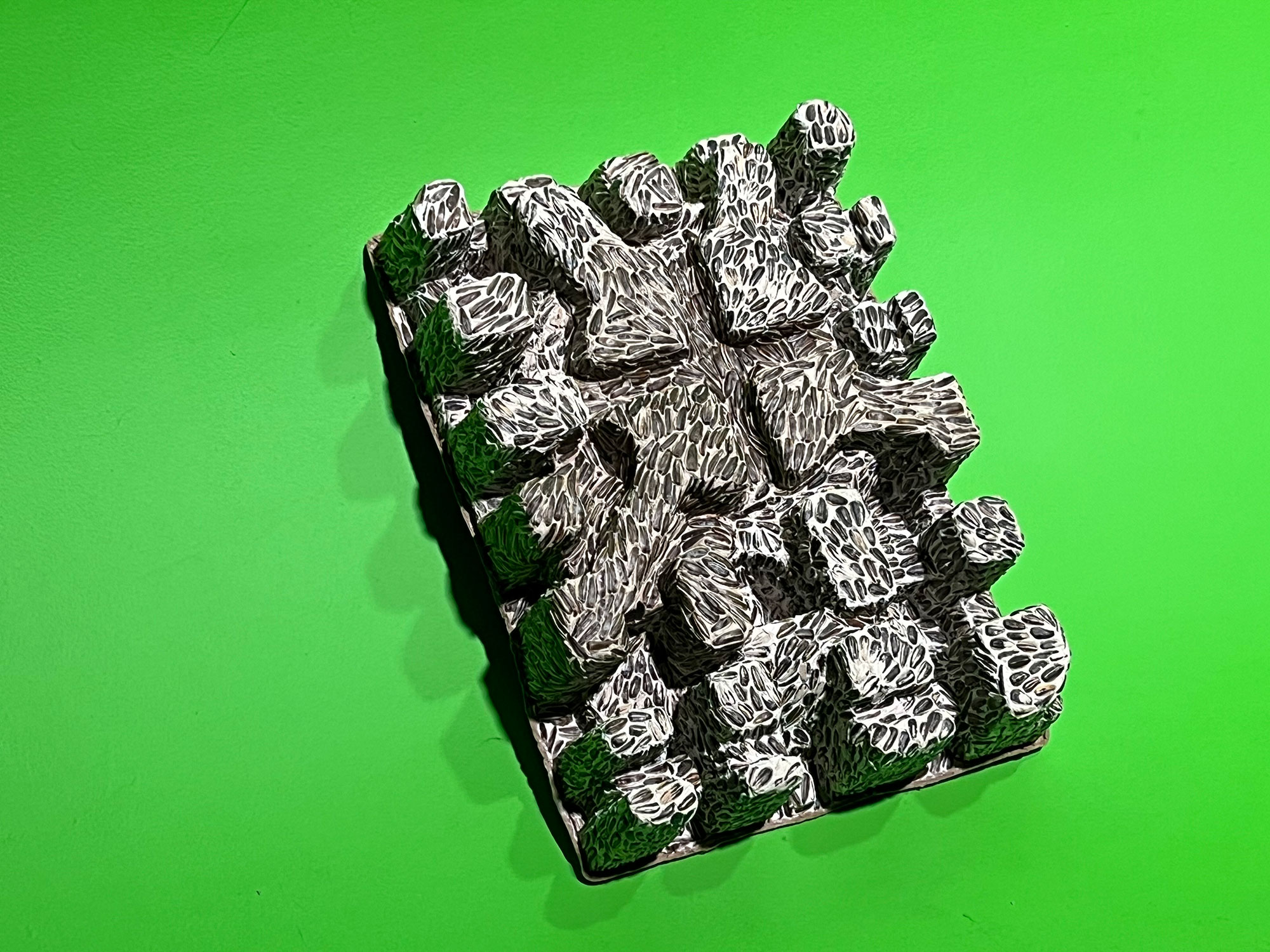

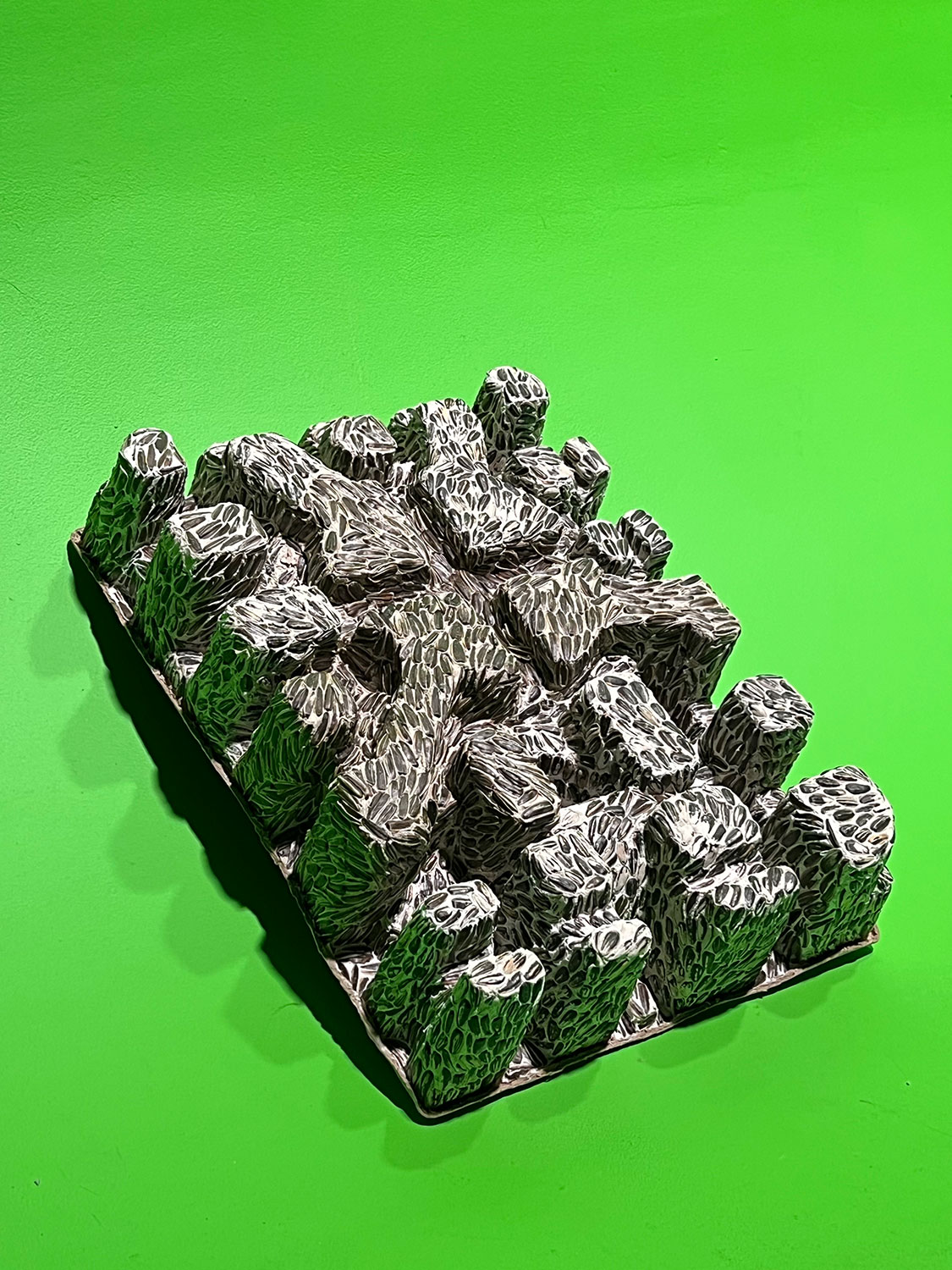

Pulp Fiction offers a meditation on the strange loop in which posthuman and human infrastructures meet. A simple and familiar pulp insert used for industrial packing services is covered with the discarded shells of sunflower seeds. The shell is the infrastructure of the seed. It is the matter that enables the movement of another matter (the seed), as Brian Larkin (2013) might argue. The casing of the shell supports the movement of seeds as they are dispersed as well as their movements of growth. The pulp insert is another such piece of infrastructure, providing protection to the commodities within, securing them inside yet another casing (the box). The pulp insert is thus a biomorphic design based on a simple natural premise: the shell.

What is contained within the shell is consumed. Seeds are eaten just as frequently as they turn into sprouts. Commodities nestled within the pulp insert are also consumed. In both cases, what remain are the discarded remnants of infrastructural protection and support, now cast off as waste products. But as inoperative remnants no longer serving to support and protect, they become open for new use (Agamben 2015). They open up to artistic reinvention, whose transcendental condition of possibility is none other than the dark ecology from which infrastructural designs emerge as essential dimensions of life. Joining together the shell and the insert is papier-mâché. The insert is the result of pulping processes that take the raw matter (hule) of nature and turn it into an industrial form (morphe). Likewise, papier-mâché is pulped, chewed up, and spit out. Pulping processes are sticky processes that bind together materials, actions, and spheres of life into strange loops. Instead of folding (as it is cherished in Deleuzian [1992] ontology), pulping mashes and adheres. The pulp of the world produces a sticky ontology of adhesion to surfaces that results in a thickly layered set of pulped materials, each binding to one another (insert to papier-mâché, papier-mâché to shell, and thus transitively shell to insert, and vice versa).

As Maurice Merleau-Ponty once observed, “Dampness, oiliness, and stickiness belong to a more complex layer of structures” (2002, 368) than smoothness. The complexity of structure described by Merleau-Ponty can be explored through aesthetic pulping practices in which layers of stratified existence dissolve and become tacky, sticking to what passes over and through them. What sticks then becomes hard, yet this hardness is not immune to the outside. Instead, it incorporates the outside into its pulpy surface. It is not a hardening against otherness but a hardening with otherness, emphatically emphasizing its relationship rather than opposition to the other. To pulp is to be decomposed so as to be recomposed in a complex loop with otherness.

These loops are spatial but also temporal. The time of dark ecologies is the time of the circle, of the return of the potentiality of the discarded, of the chewed up, spit out, and pulped. Pulping makes nature useful for human purposes, but it also has the potential to make products useless, to return them to inoperativity. Pulping is a material process of re-cycling, of chewing on the pulp of life to produce surfaces and substances that stick. Pulping produces a sticky time that binds together the past, present, and future in ways that refute the temporal linearity of clock time. Memories of chewing, of ruminating, of adhering are encrusted together. The resulting sculpture is a work of pulp fiction: an infrastructural object that has lost its function and now exists in a time of suspension. But for all those reasons, it is darker than ever.

Co-author: Tyson E. Lewis

References

Commentary by Juuso Tervo

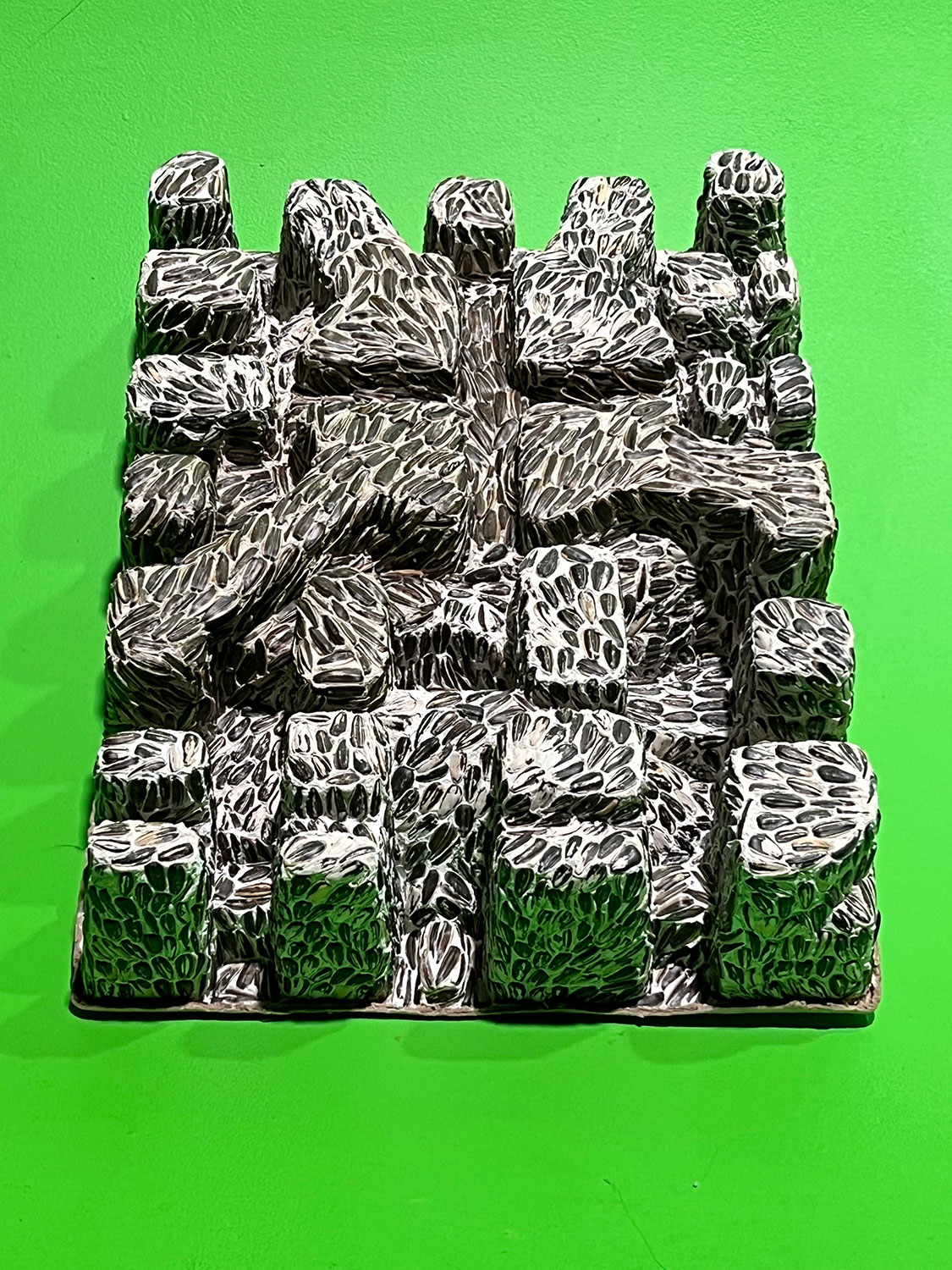

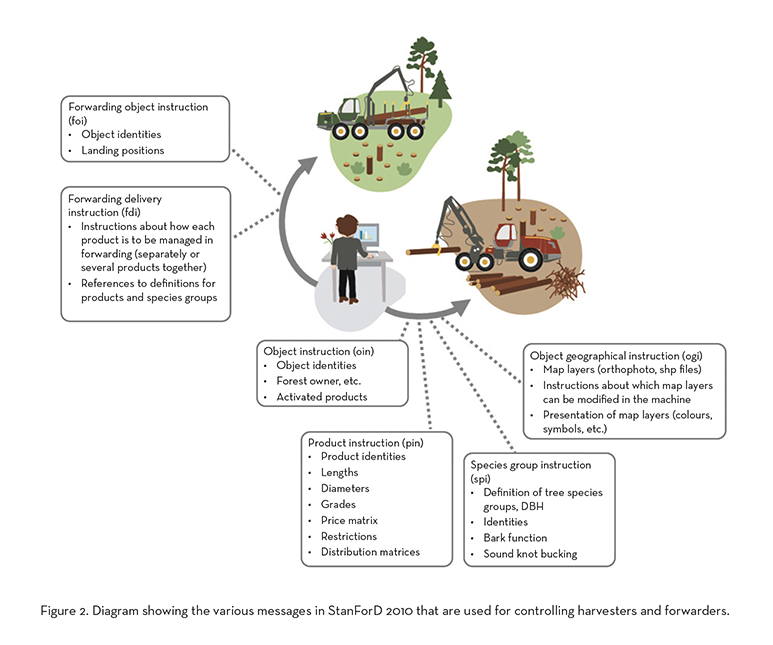

There are several ghosts in the shells we see—one of them might bear the name of StanForD 2010. StanForD 2010 is a forest machine communication standard originally developed in the Nordic countriesbut which has become a global industry standard “used by all major manufacturers of forest machines applying the cut-to-length (CTL) method” (according to Skogfors, one of its developers). CTL is the one of the most common methods in forestry (at least in the Nordic countries) in which one machine (harvester) cuts and portions each tree on site according to its potential uses (timber, pulpwood, fuelwood), and another machine (forwarder) collects and arranges the wood to be transported further. StanForD 2010 operates akin to the central nervous system of the entire operation: it not only helps to designate how many and which trees are to be cut, but it also helps to define how they are cut—that is, which (if any) portion of each individual tree will be used as timber, which as pulpwood, and which as fuelwood. In countries like Finland where major forest companies handle the process from beginning to end—not the landowner from whom the wood is bought—the data that drive the use of StanForD 2010 often derive from the market analyses of the companies themselves. In short, if StanForD 2010 functions as the central nervous system, markets are the brain that decides how this system operates.

In 2019 Finnish landowner Toivo Hyvärinen won a court case against one of the biggest forest companies in Finland, UPM. Central to their dispute was the very way the trees were cut: instead of treating them as timber (which is more profitable for the landowner), the operating system in the harvester had identified Hyvärinen’s forest to consist mainly of pulpwood (which is the central domain of UPM’s business). Upon being asked to provide the data used by the harvester, UPM first said that the machine’s printer was broken. In court, they announced that the harvester had been sold abroad, which is why all files were wiped out from its operating system. Obviously, this did not convince the court.

When engaging with Nasrin Tork’s Pulp Fiction, I found myself thinking not only the loop-like, chewy ontology of the pulp but also communication standards like StanForD 2010 that partake in the process of giving “the raw matter (hule) of nature … an industrial form (morphe).” Indeed, when using StanForD 2010, the position of the blade on the tree’s surface and, subsequently, the further uses of its matter, is determined not by the person cutting the tree per se but instead by the speculative logic of the global wood industry. Considering that the trees used for making pulp are thinner—and thus younger—than what is required from timber, this means that hule turns to morphe on an infrastructural pace; a pace that is fueled by the increased demand for packaging material used in online shopping. Contemporary pulp fiction is, as Tork points out, also a fiction of time: a combination of fluidity (speculation) and fixity (standardization) that cuts through infrastructures of matter and form.