Trespass Livestock and the Liquid Border

…with text by Margret Grebowicz and photography by Maria Whiteman

Where the Border Is a River

Inside the visitor center at Big Bend National Park, there’s a little plaque that reads, “Who is the most dangerous animal in the desert?” Below it, a door opens to reveal a mirror: it is not the coyotes or scorpions you might fear encountering while camping in the West Texas high desert, but you. It’s a charming detail, reminding visitors (especially young ones) that this place, which seems impervious and even hostile to humans, is delicate and vulnerable to their tiniest decisions and actions.

In recent years, however, the biggest human threat to the park has come in the form of farm animals crossing the border from small Mexican ranches into the park. Here, the lush, arid grasslands of the Chihuahuan Desert, which include a variety of endangered plant species, make for the best grazing for hundreds of miles around—and the border is nothing more than the meandering Rio Grande.

The trespass livestock problem is not new. It has been an ongoing phenomenon since the park was established in 1935 (Morales 2017). For other national parks, trespass livestock are a domestic rather than international issue, with domestic cattle prohibited from grazing on National Park Service (hereafter, “Park Service”) land. Not that conservation and grazing cattle are always mutually exclusive: Bureau of Land Management land can double as a working cattle ranch, like Las Cienegas National Conservation Area in Arizona. But in Big Bend, something unique is happening. Aerial counts from the past few decades have shown a minimum of around one hundred farm animals inside the park on any given day, and all have been found to originate in Mexico. They come from ejidos (unfenced community lands) or from larger, private Mexican ranches. According to the park’s most recent Trespass Livestock Management Plan, from 2018,

"Most trespass livestock that wander or are herded into the park have indicators of their domestic status, including but not limited to brands, ear-tags, collars, horseshoes, and occasionally bells. Given the economically challenged condition of ejido communities and farmers in Mexico, it has long been advantageous for livestock owners in Mexico to make use of grazing opportunities in the park when possible. Sometimes this is inadvertent, but often it is intentional (Carrera 1996). In all cases, it is illegal." (National Park Service 2018, 4)

My goal in what follows is to describe this phenomenon in order to better understand the reasons for its intractability. It is, after all, remarkable that an activity that causes so much environmental harm simply continues in a region as heavily policed as the US southern border and in an area as closely monitored and designed as a national park.

As the mainstream media focus on cartel-related border crossings—in the form of human and drug trafficking—and on contending with the humanitarian crisis encapsulated under the heading of “migration,” Big Bend faces its own border crisis, whose impacts on the “resource” (as the Park Service calls the park) are serious and long term. And precisely because international trespass livestock are a problem limited to Big Bend, it’s a key to understanding the southern border in general: the border is not only international but is also profoundly local, a vast and diverse terrain of localities. The differences among different borderlands along the southern border are not only physical/topographical but ideological/imaginary—something border policy, as it is currently written, cannot “see.”

In what follows, I show that trespass livestock movements call for us to reimagine the border as not a thing (like, say, the border wall or the river), or even a place, but as a set of practices. Bordering emerges as something human beings do—as they create and enforce immigration policy, but also as they break those laws and create alternatives that are better suited to their particular conditions.

Reframing the border as “bordering” allows for a richer awareness of the different areas that it comprises, which differ from each other not only topographically but also—crucially—in terms of stakeholders, public buy-in, levels of media attention, and degrees and types of agency. We could talk about these localities in terms of ecologies, which would illuminate certain details. But bordering (the gerund) illuminates still other details. The most profound lesson of trespass livestock is that bordering is not just sets of practices of discrete subjects—in this particular microcosm, it emerges as distinctly multispecies, responding to ecosystems and shaping them in turn. “Bordering in the Anthropocene” calls for new multispecies attunements, out of which more just and sustainable border policies might stand a chance of being born.

Where a Border Park Is a Border Community

Big Bend is the only national park whose boundary is also the border with Mexico, a border across which illegal movements of various forms happen constantly along its entire length.

Until recently, control measures to round up the cows, horses, and burros herded back and forth across the river from Boquillas and Santa Elena, the small rural villages on the Mexican side, have been relatively effective. These included flyovers and aerial counts as well as routine roundups by park rangers and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) agents on horseback and foot. The animals are subject not only to environmental laws but, as “foreigners,” to US customs law. Under USDA regulations, all animals crossing the border from Mexico must be quarantined and undergo veterinary inspection to meet health and disease certification requirements. The results of these vet checks determine who gets to live: all healthy cattle are sold for slaughter (unless claimed by an owner, for a fine), while healthy horses and burros are sold at auction. All sick animals are either euthanized or sold for slaughter. None of them are returned to their owners.

But the cost of losing entire individual herds once in a while is smaller than the gain that grazing on park grass brings to whole communities in the long term. In other words, despite massive financial losses, herding cattle into the US is still “worth it” for the vaqueros (cowboys). And as long as this is the case, the practice stands no chance of being eliminated. New livestock will continue to show up, regardless of how many are confiscated.

As Park Service budgets continue to shrink, trespass livestock are growing as an environmental hazard. The animals are eating and trampling plant species out of existence, causing erosion, and carrying invasive species on their bodies—such as buffalo grass—that throw the ecosystem out of balance. Unchecked, this will have long-term effects on the river corridor and beyond. The park is home to endangered native plants like the Guadalupe fescue (Festuca ligulata), a perennial grass on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s List of Endangered and Threatened Plants, and is a critical habitat for many endangered native animal species, like the Rio Grande silvery minnow and Mexican long-nosed bat, as well as species that were previously extinct from the park for decades, like black bears. Impacts from trespass livestock include soil erosion, damaged soil crusts, and networks of trails called “terracettes,” in which soil conditions are highly altered and plants are killed off (National Park Service 2018, 8). Sometimes these trails pass through historic and archaeological sites and destroy structures and rock art. We are talking about long-term damage to both natural and cultural resources.

Wilderness law dictates that the park’s most highly protected areas are also the least managed, and all proposals for how to manage or mitigate pervasive impacts must themselves be evaluated for their potential impact on the ecosystem. Indeed, Big Bend’s proposed Trespass Livestock Management Plan was cleared through the National Park Service’s official Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI).

The FONSI alone is not enough for implementation. Realizing the Management Plan will require a much more nuanced reading of the social and political relationships in the region, which are at once very small scale and “local,” such as relations between families and neighbors, and quite literally international, spanning one of the most contested, dangerous, and porous international borders in modern history. But the expertise of the Park Service is usually centered either on conservation science or law enforcement or both (as when the job of the ecologist is to enforce compliance with environmental laws) and much less on local culture and social relations.

This is perhaps most apparent in the following account of why eliminating trespass livestock in Big Bend is not an environmental justice issue: “Trespass livestock in the Big Bend region are not used by minority or low-income populations within the US or its territories for food or income. They are used by populations within Mexico, but those impacts are not analyzed in this EA [Environmental Assessment]” (National Park Service 2018, 12). In other words, the EA did not analyze the Management Plan’s economic impacts on the Mexican farmers—those most affected by the proposed plan—presumably in part because it was funded by the US government. To its credit, the Park Service is transparent about not considering Mexican interests when issuing the FONSI. But the FONSI is based on explicitly excluding the plan’s potential impact on the most vulnerable population only because these impacts are not on US soil—a stunning example of the maze of conceptual and empirical blind spots around the trespass livestock issue. As the report states, attempts to eliminate this practice will not result “in any impacts to minority populations or low-income populations in the US,” and thus, “this topic was dismissed from further analysis.” (National Park Service 2018, 12). This is a common result of what is called “technocratic governance”: the decision-making process is so top-down and fact based that it typically excludes consideration of the communities on which it has the most significant impact.

This calls for more context. But how does one contextualize such a situation? One possibility is to think in terms of the category of “border park.”

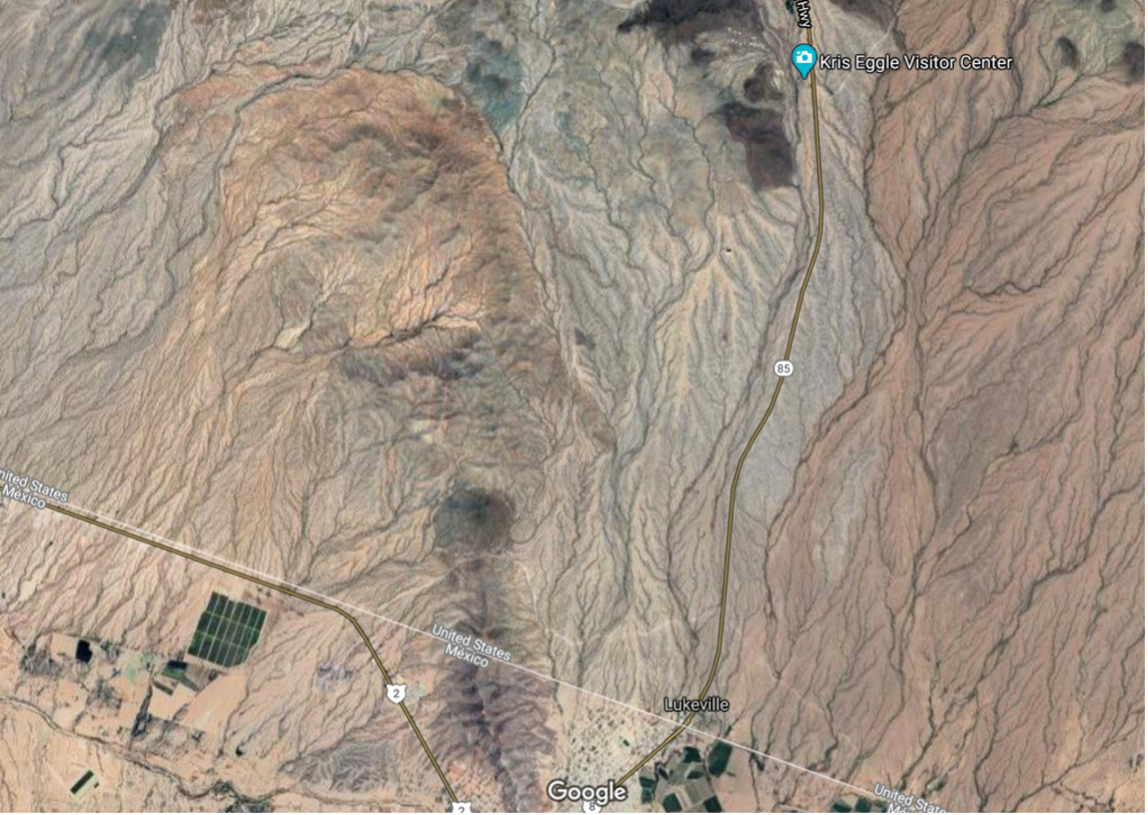

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and Coronado National Memorial, both in Arizona, are National Park Service units with the international border marking their southern boundaries. They are the closest analogues to Big Bend, though neither is a national park. In these Arizona units, Border Patrol activity is much higher, as is its corresponding impact on the designated wilderness that makes up most of these units. Both are home to the now-infamous border wall, which began as fencing erected under the Obama administration and was expanded by the Trump administration into a taller and different kind of structure. In addition to this, Border Patrol agents routinely override the Wilderness Act by driving motorized vehicles into the desert. ATVs, drones, and helicopters are a regular part of everyday life at Organ Pipe.

By comparison, Big Bend Border Patrol agents carry out their duties inside the desert on horseback. Helicopter use is extremely restricted inside Big Bend. And there’s no physical barrier indicating the border at all along the park’s 118-mile-long Rio Grande boundary. According to the Management Plan, periodic flooding would damage or destroy fencing and create hazards to river navigation. It would also block access to drinking water for wild animals (National Park Service 2018, 4).

Both Organ Pipe and Big Bend are subject to the Wilderness Act (Coronado is not), which would normally prohibit motorized incursions like those at Organ Pipe. But Border Patrol agents are allowed to override many environmental protections because of the unusually high level of border crossing activity there. Big Bend is markedly different. There the level of activity is lower, and thus the corresponding Border Patrol presence—and the forms it takes—has less impact. Ironically, however, this has resulted in the “border crisis” of trespass livestock and in impacts that the Park Service is less and less able to get under control.

In Big Bend, the river carries its own wilderness designation, “Wild and Scenic River,” one important reason it was not so easy for the Trump administration to put up a border wall there. The river corridor is comanaged by US and Mexican park authorities. As the river changes its course, as all rivers do, so does the national border, which is officially its “thalweg,” or deepest point.

It’s not hard for the locals to move cattle back and forth across the water. Boquillans do so daily as a job: they make US dollars by charging tourists for a photo of a horse (or the privilege of getting on one), by selling trinkets to tourists, or by singing for money (see Grebowicz 2018 and Whiteman 2016). On the Santa Elena side, the activity is less visible because it is limited to herding—in other words, the human presence from Mexico is visible in the form of the cows passing back and forth.

All of these activities are against the law, but Border Patrol has bigger fish to fry. Law enforcement inside this park must be selective. They have consequently managed to maintain good relations with Boquillans and Santa Elenans despite the chaos that changes in border policy typically introduce into border communities. And there’s no avoiding the fact that success in fighting the cartel depends in large part on maintaining these good relations with the border villages and Mexican authorities.

Indeed, Big Bend is an example of excellent cross-border relations over the last few decades of border upheaval and policy changes. Such good relations are key to the sustainability of small, old, border-region communities. While more intense policing of Mexican farmers and more consistent roundups may seem like the best answer, a trespass livestock “crackdown” would be a challenge to implement, given what there is to lose. Park authorities are continuously faced with walking the delicate tightrope between protecting the resource and protecting their longtime, hard-won, cross-border relationships. While they cannot sacrifice law enforcement for the sake of getting along, they must at the same time continue to get along.

In places like Big Bend, the border functions as a border not only thanks to how it restricts what people can do but also thanks to goodwill, cooperation, and communication across the boundary over generations.

Spectacles, Blind Spots, and Movements

But all of this complexity stops at the human level: human economies, human interests, human agency. The challenge is to offer not only more but conceptually richer context, which we are tasked with creating: to begin thinking of the border as a multispecies space or of bordering as multispecies practices and agencies.

Trespass livestock movements do not happen spontaneously. But they also do not happen only because some humans actively herd some animals across the river. The movements continue thanks to particular structures of thinking and ways of seeing, to perspectives, framings, and imaginaries that allow them to continue. This is the case for all animal movements in the Anthropocene, where “wilderness” and “wildlife” are no longer factual descriptors but legal designations that bring with them laws, architectures, technologies of surveillance, and ways of seeing (“Making Way for Wildlife,” New York Times, June 2, 2021).

From a certain perspective, the blind spots that allow grazing in Big Bend to continue are not just a border problem. They have been woven into the fabric of the wilderness idea at least since its codification in law in 1964. In William Cronon’s landmark critique, “The Trouble with Wilderness,” he points out that a framework that sets things up in terms of human versus nonhuman forces—as wilderness ideology does—obscures “conflicts among different groups of people. [ . . . ] If in answering these knotty questions we resort to so simplistic an opposition, we are almost certain to ignore the very subtleties and complexities we need to understand” (1995, n.p.).

It’s not only differences that are obscured but particular people, especially those that don’t easily fold into the wilderness fantasy—namely, the rural worker. As Cronon notes,

"The dream of an unworked natural landscape is very much the fantasy of people who have never themselves had to work the land to make a living—urban folk for whom food comes from a supermarket or a restaurant instead of a field, and for whom the wooden houses in which they live and work apparently have no meaningful connection to the forests in which trees grow and die. Only people whose relation to the land was already alienated could hold up wilderness as a model for human life in nature, for the romantic ideology of wilderness leaves precisely nowhere for human beings actually to make their living from the land. [ . . . ] What are the consequences of a wilderness ideology that devalues productive labor and the very concrete knowledge that comes from working the land with one’s own hands?" (n.p.)

In Big Bend, we see some of the consequences of this ideology expressed literally. The differences between interested human parties are not the only ones obscured by the wilderness idea; so too are those between different nonhuman forces, with domestic animals rendered virtually invisible and wild animals the objects of the extensive surveillance, tracking, measurement, and record-keeping emblematic of wildlife management in public lands.

And perhaps the strangest and most powerful blind spot is that of the visiting public, for whom wilderness often functions as a spectacle and harbors many projections, from the nature of the environmental crisis to what it means to be human.

The fact that Big Bend’s border is the river is not the only reason that the park was spared a wall. There has always been major resistance to the idea of unsightly fencing in this park, at least in part because Big Bend is so beloved by Texans. While almost all of the border in Arizona runs through public lands, Texas as a state has almost no public lands to speak of. Big Bend has long been considered the state’s natural crown jewel and is treated accordingly, with multiple conservancy groups involved in its protection. While so much of the US border struggles with the consequences of fencing on public lands—around 80 percent of the border in Arizona is on public land—this Texas treasure still enjoys a border that is beautiful and that creates a visitor experience reminiscent of a different, simpler time.

According to the Management Plan, “Visitors most likely to be affected by trespass livestock or their management are those staying overnight in backcountry areas and those using the river for overnight trips” (National Park Service 2018, 21)—in other words, not the average national park hiker or someone enjoying the scenic drive but the more fit, experienced, and determined backcountry backpacker. Not surprisingly, hikers like encountering megafauna on the loose inside the park, especially horses. While the gentle grasslands around Santa Elena Canyon feature herds of cows, on the park’s eastern end horses wander around in the rugged, mountainous terrain, making for a very different visitor experience.

These horses are not mustangs, which are considered something akin to wild animals, or even feral horses. Thus, they are not subject to herd management under the Wild Horse and Burro Act, which is supposed to ensure the healthy life of grazing habitats on public lands. But the mustang fantasy is reinforced by the fact that wild horses do live in habitats exactly like these throughout the intermountain West.

Horses are the most iconic animal figure in the history of the American West, and the mustangs that still roam these lands in herds are direct descendants of those horses brought to the Americas on the voyages of Columbus. This history has a mixed effect on the wilderness imagination. Wild horses are considered part of the natural Western landscape, but what counts as a truly wild horse, as opposed to stray livestock, is controversial, as the case of Arizona’s Salt River horses demonstrates. [note 1] At the same time, the horse is not native to any of the protected lands in the West, because horses are not native to the Americas—which means that almost all national parks are charged with removing them in order to preserve the original character of the wilderness. [note 2] The Salt River horses are protected inhabitants of Tonto National Forest, but it is Arizona state law that protects them, not federal law, and only on the grounds that they are historic and beloved by visitors (Salt River Wild Horse Management Group 2017). Horses straddle the space between wilderness and domestication in the American Western imagination and are thus complicated agents in shaping the future of public lands.

From another perspective, however, Big Bend’s location on the border matters very much to which animals are visible to the mainstream environmentalism that the general public espouses. In border news, the only movements—and constraints—of interest are those of humans, though certainly not of the local farmers. And relatedly, the welfare of animals in the context of conservation on the border is usually limited to the wild and endangered, not the domestic and mundane. The southern border is a land of cops and robbers (Border Patrol and illegal border crossers), majestic wild animals, boundless desert vistas, and dirty, dangerous border cities of legend like Brownsville and Tijuana. The less filmic realities that have massive consequences on both sides—ever-less sustainable agriculture and ranching, border communities struggling to remain unified despite increasing militarization—tend to fall into the background.

This is most visible in the fact that recent environmental critiques of heightened border security have focused almost exclusively on the border wall. This has created a culture of thinking about the border in terms of the movements of wild animals, many of them endangered species, across the fragile habitats the border wall disrupts (“6 Ways the Border Wall Could Disrupt the Environment,” National Geographic, January 10, 2019). But the wall has many effects. It is itself a hybrid, complicated object with a history and present (for instance, the Park Service tends to call it “new fencing” or “new fence” rather than “border wall”). One important consequence of the wall in Organ Pipe is that it ensures that farm animals do not move across the border, thus also protecting that habitat for wild animals—including several species on the endangered species list, like the lesser long-nosed bat, the desert tortoise, and the Sonoran Pronghorn, one of the most endangered animals in the United States. If biodiversity conservation is the goal, the movements of some animals across the border must be constrained in order to protect crucial habitats for other animals. Ironically, the border wall is effective in this.

The Border Is Not What You Think. The Border Is Not What You See. But Thinking and Seeing Are Modes of Bordering.

That 95 percent of Organ Pipe is designated wilderness and therefore under the highest level of environmental protection means little these days. Border Patrol is entitled by law to override any and all wilderness laws in order to execute its mission of protecting the border, as long as it can demonstrate exigency. And however the present situation is framed—as migration crisis, border crisis, or war on drugs—it appears as one giant, constant condition of exigency. The numbers of migrants apprehended inside the park daily is currently in the hundreds, and the rate of drug and human trafficking through this particular corridor is as high as it was in 2003, when the park was shut down because it was declared too dangerous for visitors. The only fact that dampens this “exigent” status is the realization that these levels of border crossing are probably here to stay.

As I have noted elsewhere, Organ Pipe’s border crisis is also, in no uncertain terms, a litter crisis (“What Litter Tells Us about the Border Crisis,” Slate, June 6, 2021). The amount of trash left behind by all the humans in transit is staggering. Border Patrol and the National Park Service often work together on cleanups but cannot keep up with the mounting refuse in the park. Yet another way Border Patrol helps the Park Service fulfill its mission is by responding to signal fires. Border crossers who are lost and dehydrated and ready to turn themselves in to Border Patrol often light fires to signal distress. Border Patrol agents must hurry to reach the vulnerable humans in time and put out those fires before they burn down massive tracts of the vulnerable desert, destroying critical habitat.

In stark contrast, Big Bend is working on getting a “cowboy,” a mounted law-enforcement park ranger, to herd trespassing animals full time. The fact that the focus is so much on animals—and on using animals to respond to animal incursions—makes it feel more like a nature space, more “sustainable.” The trespass livestock crisis in Big Bend appears much less dramatic and doesn’t carry the weight of the humanitarian crisis that accompanies human border crossings.

And it’s precisely these stark differences that illuminate how much the border crisis demands a multispecies attunement. By this, I mean a change in practices and even research methods: from treating the Anthropocene as an object of study to seeing from inside it. The border is not what we think it is—but it is very much a question of how we think. It is not what we see—but it is a question of how we see. Turning our attention to livestock is not about weighing human versus animal needs but about shedding light on the border as a messy tangle of human and animal needs, a contested space subject to the complications of neoliberal management in (and of) the Anthropocene.

The situation in Big Bend—which cannot be analyzed outside the larger context of the southern border and its relationship to US public lands—is a microcosm that reveals why the border doesn’t exactly “work” and also explains the effects of various attempts at tightening “homeland security,” which never successfully mitigate most of the issues they are supposed to address. Its intractability sheds light on how much attention and aid is necessary for border parks and border communities to remain sustainable—as simultaneously border, park, and community.

What—and how—borderings do what they do depends on various levels of agency at work “inside” the multispecies networks that make up what border policy continues to treat as a homogeneous, human whole rather than a multivalent, ever-changing phenomenon. The intractability of the livestock problem is not due to its being unchangeable but the opposite: its exquisite adaptability in the face of border policy’s failure to keep up. And more generally, the lesson here is that the failure of the border is due to our general inability to see the kind of thing it actually is.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Text by Margret Grebowicz. She thanks Mark Williams, Raymond Skiles, Bob Krumenaker, Marie Landis, Rick Gupman, Rijk Morawe, Jessica Garcia, Matt Stoffolano, JoAnn Blalack, Peter Holm, Lorraine Eiler, and Charles Trost. All of the opinions reflected here are Grebowicz’s own and in no way represent the National Park Service.

REFERENCES

- Cronon, William. 1995. “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Personal Website. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.williamcronon.net/writing/Trouble_with_Wilderness_Main.html.

- Grebowicz, Margret. 2015. The National Park to Come. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Morales, Carlos. 2017. “In Big Bend National Park, Grass is Greener for Trespassing Livestock.” Marfa Public Radio. August 11, 2017. https://marfapublicradio.org/blog/in-big-bend-national-park-grass-is-greener-for-trespassing-livestock/.

- National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. 2018. Trespass Livestock Management Plan: Environmental Assessment. November 2018. https://www.nps.gov/bibe/learn/news/trespass-livestock-management-plan-finalized.htm.

- Salt River Wild Horse Management Group. 2017. “SRWHMG Commends State & Feds for Protecting Salt River Wild Horses.” December 29, 2017. https://saltriverwildhorsemanagementgroup.org/salt-river-wild-horse-management-group-commends-state-feds-signing-mou-protect-salt-river-wild-horses/.

- Whiteman, Maria, dir. 2016. Borders and Horses: Texas and Mexico. Dual video channel, 16 min. Geologic Time. Big Bend National Park, Texas. Filmed in Big Bend National Park. Shown at Open Studio, Banff Centre, Alberta, 2016.

BIOGRAPHIES

Margret Grebowicz

Margret Grebowicz (she/her/hers) is an environmental philosopher living in upstate New York. She is the author of four books—Mountains and Desire: Climbing vs. the End of the World, Whale Song, The National Park to Come, and Why Internet Porn Matters—and is currently finishing a new short book, Rescue Me: On Dog Abundance and Social Scarcity. She is interested in wilderness, animals, and desire. Her recent articles have appeared in Slate and The Atlantic, on topics ranging from Himalayan mountaineering to national parks on the southern US border to the utopian imaginaries behind dog training. She’s the founding editor of a new short book series for Duke University Press, called Practices, and has a serious mushroom foraging practice herself.

Margret Grebowicz (she/her/hers) is an environmental philosopher living in upstate New York. She is the author of four books—Mountains and Desire: Climbing vs. the End of the World, Whale Song, The National Park to Come, and Why Internet Porn Matters—and is currently finishing a new short book, Rescue Me: On Dog Abundance and Social Scarcity. She is interested in wilderness, animals, and desire. Her recent articles have appeared in Slate and The Atlantic, on topics ranging from Himalayan mountaineering to national parks on the southern US border to the utopian imaginaries behind dog training. She’s the founding editor of a new short book series for Duke University Press, called Practices, and has a serious mushroom foraging practice herself.

Maria Whiteman

Maria Whiteman’s current art practice explores themes such as art and science; relationships between industry, natural energy, community, and nature; and the place of animals in our cultural and social imaginary. Whiteman (she/her/hers) is the Artist in Social Practice, Visiting Scholar at the Environmental Resilience Institute, Indiana University (2018-present). Maria has published critical texts in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas, Minnesota Review, and Antennae and an essay on Visual Culture in the John Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism, Sustaining the West (2014), and Catalyst (2016). In November 2015, she co-organized “After BioPolitics” for the Society for Literature, Science and the Arts (SLSA), Keynotes (Mark Dion and Vinciane Despret), Houston, Texas. She has also been selected as a recipient of the Visiting Scholar Lynette S. Autrey Fellowship (2015–2016). In March of 2016 “Touching” was exhibited in the Urban Video Project “Between Species,” curated by Anneka Herre at Syracuse University, New York. Walker, curated by Angela Ellsworth, was presented at the Museum of Walking, Tempe, Arizona, in March 2016. Mountain Pine Beetle and Roadside Kestrel, premiered at the Houston Cinema Arts Festival and Rice Media Centre, Houston, Texas, in November 2014. She was the Banff Artist in Residence in Extended Visual and Digital Media Arts (April-May 2016) and again in November 2016 to January 2017, in the BAIR Extended Program at the Banff Centre.

Maria Whiteman’s current art practice explores themes such as art and science; relationships between industry, natural energy, community, and nature; and the place of animals in our cultural and social imaginary. Whiteman (she/her/hers) is the Artist in Social Practice, Visiting Scholar at the Environmental Resilience Institute, Indiana University (2018-present). Maria has published critical texts in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas, Minnesota Review, and Antennae and an essay on Visual Culture in the John Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism, Sustaining the West (2014), and Catalyst (2016). In November 2015, she co-organized “After BioPolitics” for the Society for Literature, Science and the Arts (SLSA), Keynotes (Mark Dion and Vinciane Despret), Houston, Texas. She has also been selected as a recipient of the Visiting Scholar Lynette S. Autrey Fellowship (2015–2016). In March of 2016 “Touching” was exhibited in the Urban Video Project “Between Species,” curated by Anneka Herre at Syracuse University, New York. Walker, curated by Angela Ellsworth, was presented at the Museum of Walking, Tempe, Arizona, in March 2016. Mountain Pine Beetle and Roadside Kestrel, premiered at the Houston Cinema Arts Festival and Rice Media Centre, Houston, Texas, in November 2014. She was the Banff Artist in Residence in Extended Visual and Digital Media Arts (April-May 2016) and again in November 2016 to January 2017, in the BAIR Extended Program at the Banff Centre.

NOTES

2. One fascinating exception is Assateague Island National Seashore, where the loose horses are feral, not wild, and treated as a part of the island’s cultural history—but the directions to visitors are exactly like those concerning any native wild animal species in a national park.

REVIEW

The essay points to an under-addressed aspect of border / immigration debates, namely the space of “border parks” in the U.S. National Park Service and the unique place of Big Bend National Park as the only National Park that borders Mexico. Through specific address to human and non-human animal movement, and the varying degrees of tolerance with which these are permitted by the NPS and Border Patrol (BP), the author argues for potentially new frameworks for understanding borders as fluid sites of “bordering,” or what she calls “multi species practices and agencies.”

The contribution is novel in its theoretical linking of unique sets of practices that problematize conventional interpretations of borders that tend to focus on concrete physical barriers (walls, fences, surveillance apparatuses) and human subjects to the exclusion of animal and plant species and their corresponding movements. The account of adverse environmental impacts, supposedly the purview of National Parks, that are curiously overlooked in the management (or deferral of management) reflected in the policy and practices of Big Bend National Park and their cooperation with Border Patrol is especially interesting and full of curious contradictions. The essay is appropriate to Techniques Journal as it straddles academic and non-academic modes of inquiry. The photographic components blend with the evocation of place and politics to create a sense of transport and immersion into the spatial-social and non-human perspectives evoked in the scholarly text.

—Anonymous reviewer

REVIEW

(Skimming past)

Trespass Livestock and the Liquid Border

Margret Grebowicz and Maria Whiteman

The article begins with naming human-made borders—geographical, legislative, national, cultural, nomenclatorial—around the ubiquitous trespass of livestock across an infamous international border represented by a big river. The writing, and the agencies it names, wanders—”skims” is perhaps a better descriptor, as stones do when skipped across water; where mastery is not only measured by the number of skims but the beauty of intersecting ripples formed by each skim—through the myriad of network relations that touch on bordering practices in conservation, biology, agriculture, labour, and most of all multispecies lived experience, that transect, double back, thicken, blur, and sometimes overdetermine, but always making-indistinct, human made borders. As a performative piece of writing on the ever-shifting performances of bordering, this piece is a thoroughly enjoyable read (and so too the writing of this “review”) and is exquisitely suited for the special issue of TJ, especially if the Journal is itself performative of inhabiting the shifting borders of research writing between the academic and non-academic.

I read Grebowicz and Whiteman’s piece in two ways, leading to two short reviews (they are more responses than reviews; I cannot seem to follow instructions as a peer reviewer) that follow. Firstly, as an academic essay, it allowed me to construct amazing spatio-conceptual diagrams of interfering bordering practices by governments, communities, workers, animals, and wilderness, leading to an understanding that the political and justice here is highly contingent and requires an attunement to borders that borders on being as atmospheric as the landscape that it serves. Secondly, I did a skim read—in reality I did this reading first, as is common practice to sense the shape of a paper before a review—with the help of a PDF reading tool I often use to review papers and theses, called Skim®.

First response

Through a highly documentary and evidentially convincing voice, Grebowicz and Whiteman outline the various tangible and intangible boundaries that are overlaid across the landscape by governmental policy, agricultural practices, conservation, and tourism. What the writing demonstrates is that these boundaries are material-semiotic, that is agencies are afforded to entities by virtue of being named in language, enacted by law or culture, and materially performed in the landscape. Take the horse in the article. “A horse is a horse, of course, of course,” but its presence vibrates between being valuable livestock and invisible commodity, wild mustang and feral trespasser, and symbolic icon and immersive landscape, all dependent on the language of the law that transects the intangible line that follows the thalweg of the river. Nor is the horse the source of the multiple agencies present—even so, we cannot “go right to the source and ask the horse” as “no one can talk to a horse of course” (“unless the horse is the famous Mr. Ed.”). Even if we could, what the horse may have told us would be relationalities between species entangled with the human borders present; relations which cannot be expressed fully in the language that is already part of the techniques of bordering in the first place.

But if we see the horse as part of a multispecies ecology, we see other human borders emerge and dissipate, demonstrating the re-bordering technique that Grebowicz and Whiteman use continue to produce a richer understanding of both power and indifference of borders to communities, environment, and law. So too borders, once made visible and in their contradictions, that is, performed—walked, cantered, slithered, swum, transgressed—other previously unnoticed interspecies relations also emerge.

Let’s look at the second image at the top of the writing. The cowboy / -girl heading back to agricultural land in Mexico performs the international border through his / her vision ahead of familiar landscape of home, feeling relief from no longer being under possible surveillance in the National Park (with all its environmental laws), having just crossed the middle of the river (the Wall may have as well been right there), and the affirmation by his dog’s bark that the last of the horses are following. The border is registered differently by the horses, as continuous but gradually diminishing feedstock from “protected” national park where it was earlier “free” towards being locked into pens with dried hay, and the thalweg (probably the most accurate experiential location of the actual border) as the most feared part of the journey (the deepest water). The first horse feels the posture change of its rider from his/her anticipation of returning home, just after letting its rider know that they are now safely across the thalweg by a change in gait; the middle horse’s attentionality is based on following and being followed, hence the border may have never registered; and the last horse has a deferred registration of the border up to the point that it can no longer hear the herding bark of the dog. And for the dog, the border moves right behind the last horse; and so on.

Second response

As I skim the writing, Skim® allows me to highlight text that strikes me as salient which it simultaneously quotes on a separate document, along with the page numbers they came from, and any thoughts I may have had as I went along, making it a convenient memory trigger when writing my response / review.

When I exported the Skim® notes, I found that my skim reading of the writing (I did not make any notes to self) produced its own review as an unintended, and surprising, consequence. Like hand-highlighted printed text is never accurate, so it is in Skim, especially when you are reading fast, missing out words and marking part sentences and salient words as memory joggers for later. My Skim® notes produced a piece of writing that is part intentional, part peripheral, and often with missing sentence objects and argumentative contexts. After a bit of a tidy up, I thought it interesting to share it here for what it is worth: I draw no conclusions except to say that it is sort of a multispecies reading and writing; a distracted practice that imbricates imbrication of nature (human) and technology, a small dose of what David Wills calls “dorsality.”

Skim notes

– Line, 1

mexico

– Line, 1

– Circle, 1

– Line, 1

– Line, 1

– Line, 1

– Line, 1

Texas

[Note: this was me annotating the image]

4

Big Bend something unique

found to originate in Mexico

They come from ejidos

river by vaqueros—Spanish for “cowboys.”

In all cases, it is illegal.

for its intractability. It is, after all, remarkable

The border is not only international,

it is also profoundly local,

a vast and diverse terrain of localities.

but ideological/imaginary

5

trespass livestock is

that bordering is not

just sets of practices by discrete subjects—

in this particular microcosm,

it emerges as distinctly multispecies,

Anthropocene

Fresh cow dung is in the foreground.

6

checks determine who gets to live:

None of them are returned to owners.

herding their cattle into the US is still “worth it”

8

the job of the ecologist is to enforce compliance

with environmental laws

explicit exclusion of the potential impact

on the population that will be most impacted,

only because these impacts are not on US soil

Organ Pipe is home to the now-infamous border wall

9

Benito Juárez was imposed on the village

after the Mexican Revolution,

but is not recognized or used by the locals

10

its course, as all rivers do, so does the national border,

which is officially its thalweg,

Park authorities are faced

with walking a delicate tightrope

11

bordering as multispecies practices and agencies.

the intractability of trespass livestock proves that it’s necessary

Only people whose relation to the land was already alienated

could hold up wilderness as a model for human life in nature,

romantic ideology of wilderness

leaves precisely nowhere for human beings

actually to make their living from the land.

12

spectacle and harbors many projections,

the effect is that of meeting a beautiful, lone mustang,

far away from any other humans—

with a big, silent, calm horse, slowly chewing and enjoying the sun

counts as a truly wild horse, as opposed to stray livestock,

13 loose horses are feral, not wild,

14

thinking about the border in terms of the movements of wild animals,

across the fragile habitats the border wall disrupts

15

as the migration crisis, the border crisis, or the war on drugs—

it appears as one giant, constant condition of exigency.

a litter crisis.

16

BP must hurry to not only get to the vulnerable humans in time

but to put out those fires before they burn down massive tracts

The fact that the focus is so much on animals—

and responding to animal incursions with the use of animals—

makes it feel more like a nature space, more “sustainable.”

The border is not what we think it is—

but it is very much a question of how we think.

verb in the gerund, as “bordering”—

The intractability of the livestock problem

is not due to it being unchangeable,

but the opposite: its exquisite adaptability

—Steve Loo